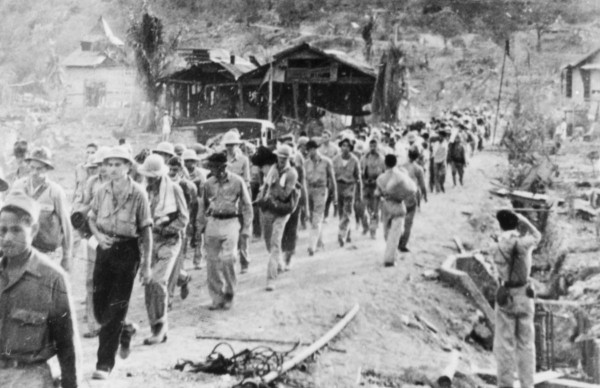

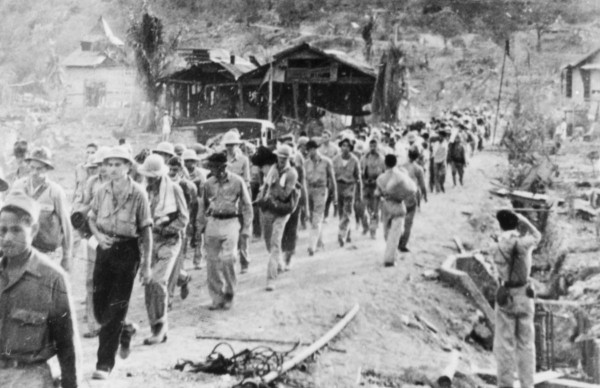

With the Imperial Japanese Army hot on his heels, Oscar Leonard says he barely slipped away from getting caught in the grueling Bataan Death March in 1942 by jumping into a choppy bay in the dark of the night, clinging to a log and paddling to the Allied-fortified island of Corregidor.

After many weeks of fighting there and at Mindanao, he was finally captured by the Japanese and spent the next several years languishing under brutal conditions in Filipino and Japanese World War II POW camps.

Now, having just turned 100 years old, the Antioch resident has been recognized for his 42-month ordeal as a prisoner of war, thanks to the efforts of his friends at the Brentwood VFW Post #10789 and Congressman Jerry McNerney.

McNerney, Brentwood VFW Commander Steve Todd and Junior Vice Commander John Bradley helped obtain a POW award after doing research and requesting records to surprise Leonard during a birthday party last month.

Because he had been in the special forces, some of Leonard’s records were redacted. Many of his military records also were destroyed in the 1973 National Archives fire. And to make matters worse, his home in the Northern California town of Paradise where he had settled down also burned down in last year’s deadly Camp Fire. Fortunately, Leonard and his wife, Mary, had moved to their daughter and son-in-law’s Antioch home two years earlier and taken some mementos there, including six diaries from his years as a prisoner of war.

Bradley said the local veterans group was happy to help Leonard, whom they’d met years earlier at Bataan Memorial Death March events in New Mexico and later at an event in Brentwood.

“Oscar is our really special veteran for the moment — he has a lot of support from us and the Paradise veterans group where he previously lived,” Bradley said. “It was 75 years ago; he needs to be recognized for his sacrifice.”

Leonard, a retired pharmacist, downplayed his exploits, which included collecting data on the enemy as a member of the Counter Intelligence Corps — predecessor to the CIA.

“I’m not that important,” he said.

Leonard joined the Idaho National Guard’s 116th Cavalry Guard in 1939 just as the war was breaking out in Europe. He says he later asked to be stationed in the Philippines because his father had served there during the Spanish-American War.

“I had heard about the Philippines — good things — and I wanted to go there,” Leonard said.

He became part of the U.S. Army Air Corps’ Coast Artillery Corps and was assigned to an anti-aircraft battery in Corregidor. But the expert marksman’s military career took a surprise turn when he was moved to the Counter Intelligence Corps. He was later transferred to Clark Air Field’s 28th Bombardment Squadron, where he observed enemy cargo ships while flying in B-10s and Japanese sea captains from the ground, writing reports on what he saw. As a cover, he worked as an airplane mechanic.

“I knew enough Japanese to get by,” Leonard said.

It wasn’t long before Pearl Harbor was bombed and 200 Japanese came overhead and took out many of the U.S. planes at Clark Field.

“People didn’t have time to be frightened,” he said.

Leonard said he and others were ordered to decommission the air field, ridding it of anything the Japanese could use by booby-trapping the arsenal with bombs. It exploded when the Japanese came in, he said.

At one point, Leonard and his colleagues tried to take off in a B-10 but were knocked out of the sky, said George Gonzalez, who is Leonard’s son-in-law, caretaker and record keeper.

While the Japanese Zero fighter planes were flying overhead, Leonard said he sensed something unusual about their flight pattern and climbed a nearby hill to find a Filipino man speaking into a radio in Japanese. The man, whom he later learned was a spy, took out a gun, but Leonard says he shot him first.

Gonzalez finished the tale.

“Oscar said the bullet hit the man’s skull and then the wall, so he picked it up and he carried it with him,” Gonzalez said, noting that Leonard kept it throughout his life until it was lost in the Paradise fire.

Outnumbered in the battle, Leonard and the remaining soldiers held back as long as they could before fleeing to Bataan.

With the Japanese in pursuit and Bataan about to fall, Leonard escaped by jumping into a bay and hanging onto a log, along with a nurse who was an expert swimmer, and paddling across the water to Corregidor, Gonzalez said.

Leonard later was reassigned back to the coast artillery unit with the anti-aircraft guns, which he said he reconfigured to fire on ships. It wouldn’t be long, though, before the young soldier volunteered to collect dynamite from nearby mines and bring the explosives south to Mindanao, a 600-mile trip that would take days to complete as they hid during the day, moving the barge only during the cover of night.

Once there, he joined the line, was given a rifle and told to aim for the officers trying to cross the river onto the island, Gonzalez said.

“We would wait until the (Japanese) got to fighting the current in the water, and we would pick them off with rifle fire,” Leonard recalled.

Later, likely because of his advanced special operations training, he would fight alongside the Moros — Muslim natives who long had resisted the Japanese.

“They (the Moros) would take the Japanese and roast them — literally,” Leonard said, noting the Moros were brutal fighters and experts with knives.

Leonard said he surrendered when the Japanese threatened to shoot fellow soldiers if he didn’t emerge from the jungle cover. He was then imprisoned in the Philippines and later in Japan. In the Japanese camp, Leonard said some of the guards beat soldiers with bamboo canes and once pulled out his fingernails in an effort to extract information.

“I didn’t give them any (information),” Leonard said stoically.

One torture tactic was to make the prisoners put their feet in buckets of freezing water, Gonzalez said.

Near the end, Leonard was forced to clean up after the second Nagasaki bomb was dropped. Some of the prisoners hummed tunes during the cleanup, he said, because they knew the bombing meant the Allies were winning.

When finally liberated, Leonard said he was inexplicably given a fresh uniform and taken away by the OSS to the U.S.S. Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay.

When Leonard finally made it back to the U.S., he weighed only 68 pounds, and it took him many months to regain his strength, yet he continued in the service for the next seven years, Gonzalez said.

“I think he did what he needed to do because he was a survivor,” said Leonard’s daughter, Ida Gonzalez. “Swimming against the current in (Corregidor) when you don’t swim — that’s a different kind of bravery.”

Leonard’s VFW friends have gathered his veteran’s medical records and more to see if he might also qualify for a Purple Heart based on his POW injuries and likely radiation exposure in Nagasaki.

Though not banking on it, they’re hoping the final award, the Purple Heart, will come sooner than later.

“He wonders why we go through all the hoopla,” Todd said. “Well, World War II was really the greatest generation — these guys are all (mostly) gone now. They have stories to tell but no one knows them.”

———

©2019 the Contra Costa Times (Walnut Creek, Calif.). Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.