A hundred years ago, at the height of the First World War, John Tolkien, a 25-year-old former lieutenant with the Lancaster Fusiliers, went walking with his wife, Edith, in the Yorkshire countryside. He’d recently returned to Britain from the battlefields of France, after acquiring a case of trench fever. Both the condition and his harrowing experiences in the Battle of the Somme, which claimed the lives of some 600,000 allied soldiers, had weakened him. The carnage continued after he left, decimating nearly his entire battalion. “By 1918,” he wrote later, “all but one of my close friends was dead.” As he walked with his wife, they came to a glade flowered with hemlock. Tolkien sat down to rest. His wife, who was struggling to restore his spirits, began to dance for him among the flowers.

This incident prompted Tolkien — now better known as J.R.R. Tolkien, the author of The Lord of the Rings trilogy — to make one of his first serious attempts at writing. The result was a love story about Lúthien, an elven princess, and Beren, a man, who wanders into her kingdom after fleeing “the terrors of the Iron Mountains until he reached the Lands Beyond.” That tale, revisited throughout Tolkien’s writing career and now published in its entirety for the first time, opens when Beren spies Lúthien dancing in a similarly described glade where “the ground was moist and a great misty growth of hemlock rose beneath the trees.” It then follows a trajectory familiar from Norse mythology: a courtship, a perilous epic quest, a dark overlord, a doomed love affair.

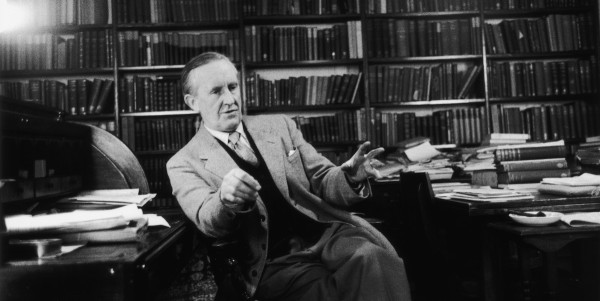

Soldiers of the 1st Battalion, The Lancashire Fusiliers fixing bayonets prior to the attack on Beaumont Hamel, July 1, 1916.Wikimedia Commons photo

For readers like myself, who read Tolkien’s more popular works like The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings — and saw the award-winning blockbuster Peter Jackson films based on them — but who can’t navigate their way to Mordor without at least a map and lensatic compass, Beren and Lúthien isn’t particularly accessible. Interspersed with lengthy expository sections by J.R.R. Tolkien’s son, Christopher, who edited the book, the resulting text is dense with geeky references to Tolkien’s other works. However, by exploring the narrative strands linking this love story with the author’s subsequent works, Christopher Tolkien convincingly reveals the dramatic extent to which his father had created not only a massive time-spanning epic but also a multi-dimensional world where every story has its backstory and every backstory a deeper history of its own.

Perhaps it’s not all that surprising that Tolkien would emerge from the horrors of the First World War and create such a comprehensive new world after intimately witnessing the destruction of an old one. That conflict features prominently throughout his books. Famously Tolkien based the hobbits of Middle-Earth, who burrow their homes into the shire and are known for their pure hearts and steady reliability in pursuit of a quest, on the working class British Tommies among whom he served in the trenches. “I have always been impressed,” he explained in later years, “that we are here, surviving, because of the indomitable courage of quite small people against impossible odds.” In a book of his correspondence, Tolkien noted how the Dead Marshes, which lead up to Mordor, with their pools of muck and floating corpses, “owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme.”

Like Tolkien, I’m also a novelist and a veteran. While fighting in our generation’s wars, I had an abstract notion that I might write some day, but despite a few false starts, I never seemed able to while in uniform. What I didn’t realize at the time was that the world I was living in was too immediate to allow me to slip into any alternate realities. It was only after I left the service — in fact, the day after — that I made what I consider to be my first serious attempts at writing fiction. Although an author’s biography doesn’t necessarily serve to unlock a deeper understanding of their work, the tale of Beren and Lúthien begs to be understood through the lens of Tolkien’s life. It might be his most intimate tale yet, a significant key to understanding not only his Middle-Earth but also of his evolution from soldier to writer. Clearly this story was close to him: The headstone he shares with his wife bears the names “Beren” and “Lúthien” in place of their own.

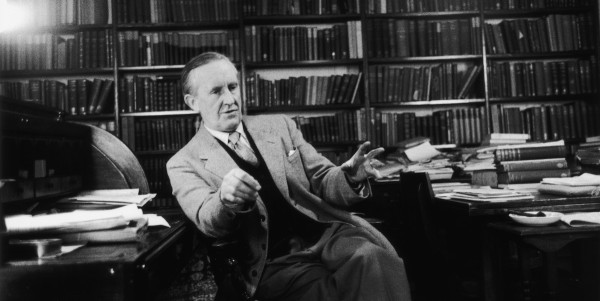

The grave of J. R. R. and Edith Tolkien, Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford.Wikimedia Commons photo

In Elvish, Lúthien means “nightingale.” One characteristic unique to the nightingale is that it will only sing its song if it hears another nightingale singing first. With Beren and Lúthien, we are now privy to one of Tolkien’s earliest and perhaps most significant works. But it is also a tribute to his wife, Edith, to whom he was married for more than 50 years. That afternoon in Yorkshire, when she danced for her husband, just home from the Great War, in a glade of flowering hemlock, she became the nightingale that allowed him to return from the front and to eventually deliver what, over five decades of writing, became his own song.

Elliot Ackerman is author of the novels Dark at the Crossing and Green on Blue.