Two decades before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor launched the United States into World War II, a Marine officer assigned to the intelligence section at Marine Corps headquarters was finishing up work on an exhaustive planning document, tens of thousands of words in length, entitled Operations Plan 712-H, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia.

The author was then-Maj. Earl “Pete” Ellis, who had previously lectured at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, and served as a staff officer under future Marine Corps Commandant Lt. Gen. John Lejeune during World War I.

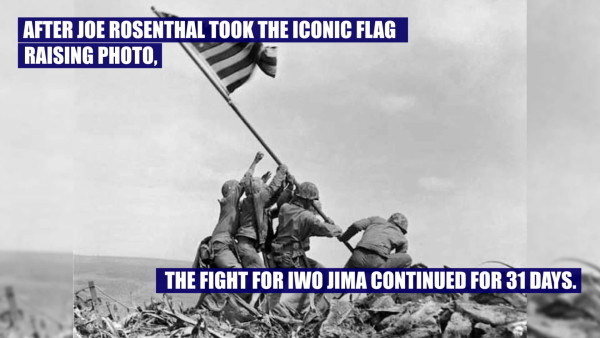

Published in 1921, Advanced Base Operations theorized that in the event of war with Japan — which Ellis claimed would begin with a first strike against the U.S. — it would be up to a reorganized Marine Corps to conduct amphibious assaults on islands across the Pacific occupied by Japan in order to develop them into advanced bases for the Navy. It would go on to become a blueprint of sorts for the “island hopping” strategy that the Marine Corps and Navy would use to fight the Pacific campaign of World War II.

“Considering our consistent policy of non-aggression, she [Japan] will probably initiate the war; which will indicate that, in her own mind, she believes that, considering her own defensive position, she has sufficient military strength to defeat our fleet,” wrote Ellis.

The mission of the Marines, according to Ellis’ plan, would be to conduct amphibious assaults on Japanese-occupied islands across the Pacific in order to establish advanced bases for the Navy and further amphibious operations.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

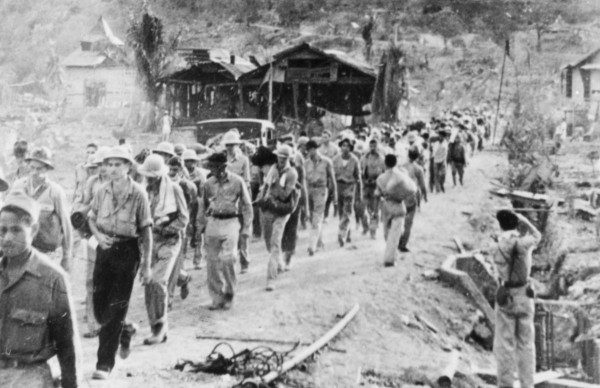

Ellis’ plan called for three phases. First, landing in the Marshall Islands, then onto the Caroline Islands, and thirdly, to continue through the Carolines into what is now the Palau Islands. Ellis also identified the vulnerability of the U.S.-held island of Guam in the Mariana Islands.

Published in 1921, Ellis and his work couldn’t account for the technological advances that would appear in the ensuing two decades. But he predicted an island hopping campaign that is quite similar to what actually happened. Indeed, many of the islands Ellis identified would become the sites of some of the Marine Corps’ bloodiest battles during WWII.

The document was also foundational in establishing a new mission for the Marine Corps, as a mobile, amphibious landing force. Until then, amphibious landings had tended to be haphazard affairs. Only six years earlier, in 1915, the massive amphibious landings at Gallipoli had turned into a disastrous defeat for allied forces. Ellis’ plans, though, called for highly detailed and synchronized landings, combined with naval bombardment, along with Marine units specifically organized around amphibious assaults.

As Dakota Wood, former Marine and senior research fellow for defense programs at Heritage Foundation told Breaking Defense in 2021, it was an “absolute foundational document for the modern Marine Corps.”

Strategic prophecy

Ellis was born in Kansas in 1880 and enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1900, receiving a commission the following year. His first assignment was in the Philippines, where he would serve multiple tours of duty over the coming decade.

The Marine Corps that Ellis entered was an organization in flux. The 19th-century mission of serving as sharpshooters and small landing parties aboard ships was ending, and as author Brett Friedman wrote in 21st Century Ellis: Operational Art and Strategic Prophecy in the Modern Era, President Theodore Roosevelt authorized the removal of Marine detachments from warships in 1908. Instead, Marines were increasingly used for garrison and counter-insurgency campaigns throughout the Philippines and in various U.S.-led interventions across Central and South America.

It was in this environment that Ellis first gained a reputation as an excellent planner and staff officer, and in 1911 he was sent to the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, first as a student and then as a lecturer.

It was while at the Naval War College that Ellis first began writing about advanced base operations, which had been proposed a few years earlier by Navy Rear Adm. William Freeland Fullam, who, perhaps unsurprisingly, considered Marines a hindrance on his ships and wanted them kept afloat separately to secure bases for the fleet.

Ellis completed four essays on the study of advanced base operations, an early attempt to plan for the future of amphibious warfare.

In Naval Bases: Their Location, Resources, and Security Ellis predicted not just that there would be a war with Japan in the Pacific, but that it would begin with Japan attempting to seize territory and “reduce the naval superiority of the United States.”

His further writing expanded on the need for the Navy and Marine Corps to seize and defend advanced bases of their own throughout the Pacific.

During World War I, Ellis was among some of the first Marine units to arrive in France, again serving as a staff officer under then-Maj. Gen. John Lejeune. While with the 4th Marine Brigade, Ellis received a temporary promotion to lieutenant colonel in 1918 and was awarded the Navy Cross and the French Croix de Guerre, along with a Silver Star, as the brigade operated under the overall command of the Army.

After a short stint as an intelligence officer in the Dominican Republic, Ellis was summoned back to Marine Corps headquarters by Lejeune, who was by that time serving as the Marine Corps commandant, and began work on Operations Plan 712-H, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia.

His earlier work was now more relevant than ever, as Japan had used its entry into WWI to seize control of several island chains in the Pacific previously held by Germany.

While Ellis’ plans would become highly influential, and seem downright prophetic given what would happen two decades later during WWII, his career was not without controversy.

Throughout his life, Ellis suffered from both depression and alcoholism. According to Friedman, one early anecdote from Ellis’ time in the Philippines recounts a time he drew his pistol and shot a Navy chaplain’s glass off a table. Years later, Ellis was reprimanded for fighting with a Navy captain.

His career was also repeatedly sidelined by bouts of what doctors at the time described as exhaustion, fits of melancholia, and hysteria. Indeed, Ellis was under constant medical supervision while preparing the planning document.

It also can’t be ignored that Ellis’ writing was tinged with racist overtones. The indigenous populations of the Pacific islands are described in his writing as being of little threat to any occupying forces, but are also at times described as having “lazy and deceitful qualities.” Likewise, Ellis also wrote that the Marines would have an advantage over Japanese soldiers because of what he described as their racially superior “higher individual intelligence, physique, and endurance.”

Ellis died in 1923 while traveling in the Pacific, and the events of his passing were themselves shrouded in some measure of controversy. Following the publication of his planning document, Ellis took a leave of absence from the Marine Corps and spent the next two years traveling, under a great deal of secrecy, around the very same islands he expected Marines to fight in. He was already in poor health and was under constant surveillance by Japanese counter-intelligence officials, Friedman wrote in his book about Ellis.

By May 1923, Ellis was in Micronesia. He was reportedly given two bottles of whiskey by local officials on an island in what is now the Republic of Palau and died shortly after. There were rumors that he had been poisoned, but the specifics of his death were never determined with any certainty. The most likely cause was alcohol poisoning and nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys.

Despite the unsavory aspects of Ellis’ story, his predictions for what the future of warfare would look like for the Marine Corps proved correct. Less than twenty years after his death, much of what he had spent his career planning for would come to fruition.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- ‘Untethered’ Air Force general: ‘When you kill your enemy, every part of your life is better’

- The Air Force’s top recruiter is personally reviewing recruits’ hand tattoos so they can enlist

- Political candidate accused of stolen valor claims his deployments are ‘classified’

- Tank warfare is still relevant, even if the Russians suck at it

- The best military field gear we’ve ever bought

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.