The Army will correct the military records of Black soldiers hanged by the U.S. military following the 1917 Houston race riots and deliver veteran benefits to their descendants in a display of historical reckoning.

The Army is setting aside the soldiers’ convictions, correcting records to note honorable discharges for 95 soldiers, and setting up a mechanism to deliver survivor benefits through the Department of Veterans Affairs. Army Under Secretary Gabe Camarillo announced Monday the service’s steps to right the wrongs of the U.S. military justice system which resulted in the largest mass execution of American soldiers by the U.S. Army.

“Today, the legacy of the soldiers, their patriotism and service to our nation — protecting freedoms that they themselves could not enjoy — is being respected, and uplifted,” said Jason Holt, an attorney and descendent of Pfc. Thomas Hawkins, at the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston, Texas. “I pray with all my heart that their souls witnessed these moments of reckoning and are set free.”

The historic change comes after the Army received petitions from retired general officers and the South Texas College of Law, requesting a review of the court’s decision and clemency for the 110 soldiers. Army Secretary Christine Wormuth directed a board in charge of military record corrections to review each of the cases. The board determined the court proceedings to be “fundamentally unfair,” and unanimously recommended that all convictions be set aside and that the soldiers’ military service be re-characterized as honorable.

In light of the changes, Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery, where 17 of the soldiers are interred, will provide new headstones with the “same amount of information that every veteran is entitled to,” said Matthew Quinn, Under Secretary for Memorial Affairs. The Army also announced 17 personal soldier pages featured on the Veterans Legacy Memorial.

“While we cannot go back in time to change the past from today on, we have an obligation to correct the record. Not only should we recognize the dedicated service of these Buffalo Soldiers, we must restore and preserve their legacies in perpetuity,” Quinn said.

In the summer of 1917, the 3rd Battalion was sent to Houston to guard a construction site that would later become Camp Logan. As racial tensions boiled up in Houston that summer, rumors and threats spurred a group of more than 100 Black soldiers to seize weapons and leave camp “thinking that they were marching in their own self defense,” Camarillo said.

The 19 Black soldiers were charged with mutiny and murder and sentenced to hanging. The first set of executions took place in secrecy the day following the sentencing hearing. Ultimately, this led to a regulatory change that prohibited future executions without review by the War Department and the president.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news and culture in your inbox daily.

“While we commemorate this momentous occasion, wherein we have literally been the arc of the moral universe toward justice, we cannot rest on our laurels,” said Rep. Al Green (D-Texas). “The pain for the 10 Black soldiers is a stark reminder of the racial prejudices that men and women of color continue to face.”

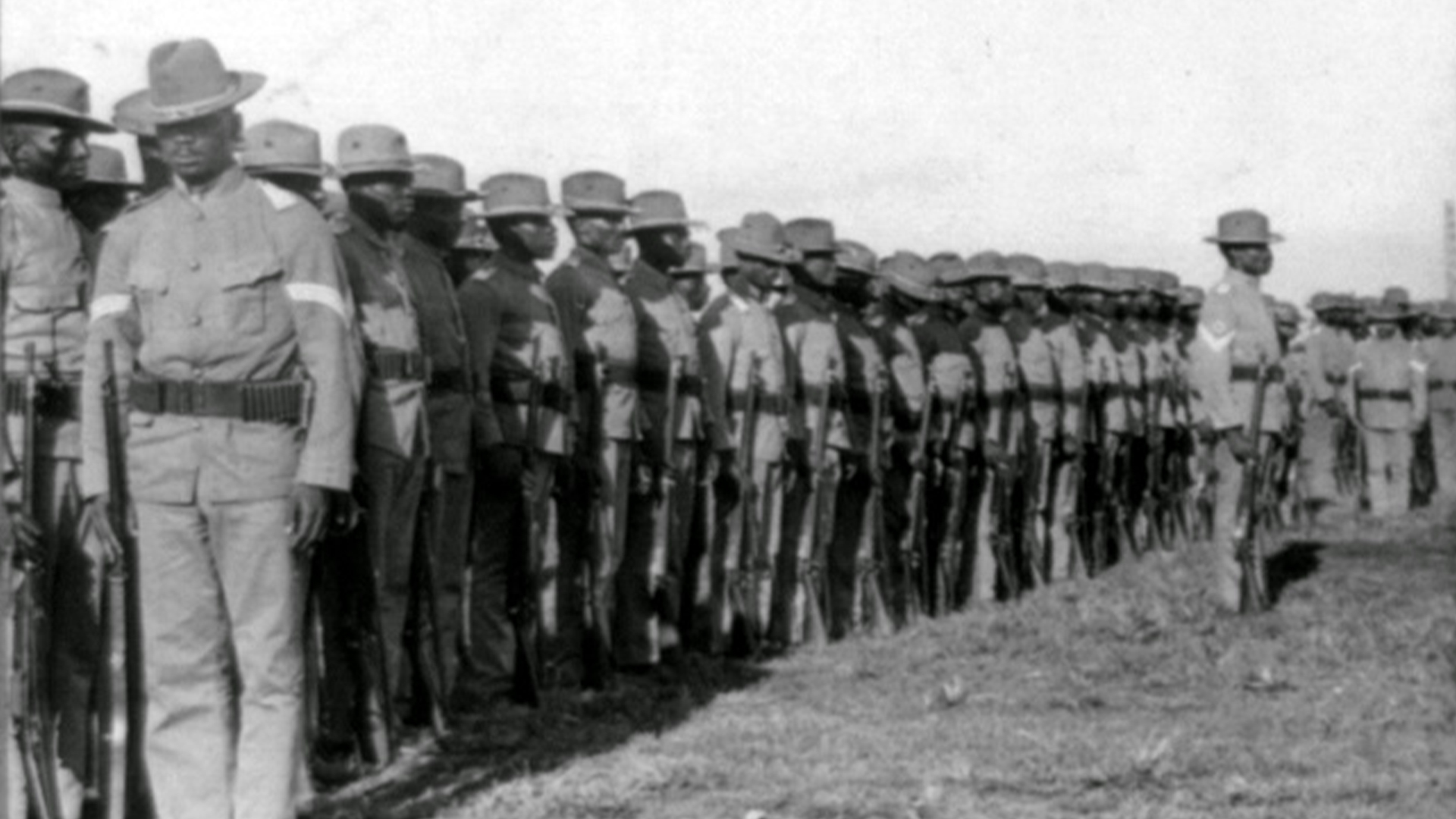

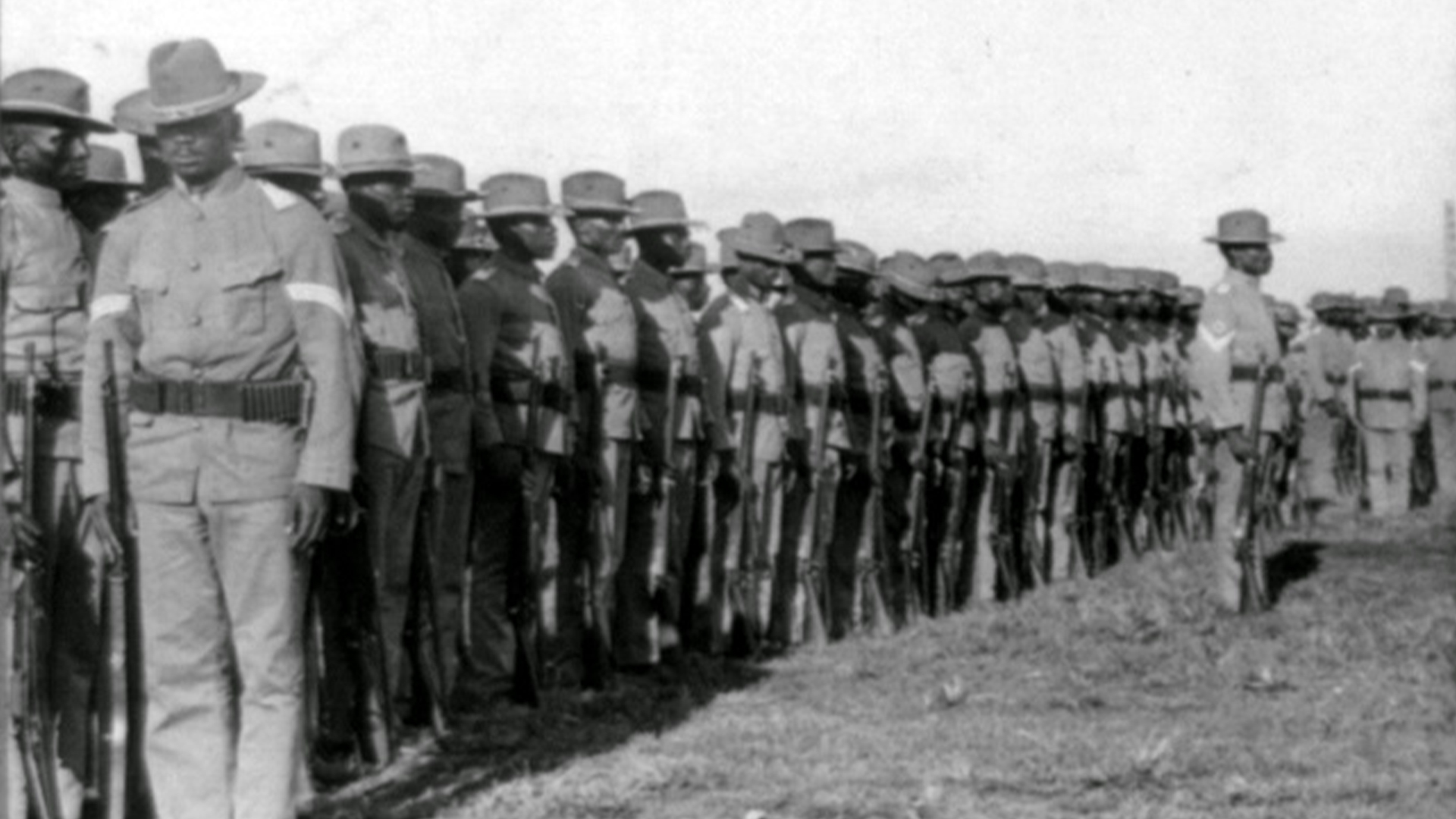

The soldiers who received clemency served in the 3rd Battalion of the 24th Infantry Regiment and were nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers,” a term for service members of color who were assigned to segregated, all-Black Army units after the end of the Civil War. The 24th regiment served in Cuba, Mexico, and the Philippines and “with their own hands, helped build the American West,” Camarillo said.

Congress established six all-Black regiments in 1866 to help with post-Civil War rebuilding efforts and to fight on the Western frontier during the American Indian Wars. Native Americans who fought against these troops referred to the Black cavalry as “Buffalo Soldiers” because of their dark, curly hair which resembled a buffalo’s coat, according to popular lore. While the origins have not been confirmed, Black soldiers embraced the nickname by World War I and the 92nd Infantry Division adopted the buffalo as the symbol for its unit patch, according to the National Museum for African American History and Culture.

All-black regiments were disbanded during the Korean War under a 1948 executive order from President Harry Truman which desegregated the military.

“Most people had moved on over the years. The Houston incident had become a historical footnote for niche academics, but the story was very much alive for the descendants of the wrongfully executed and the wrongfully convicted,” said Brig. Gen. Ronald D. Sullivan. He now serves as the chief judge of the Army Court of Criminal Appeals created in the wake of the Houston incident.

The Fort Sam Houston National Cemetary’s plaque will feature the historic reckoning of the Army’s role in hanging its troops and the “widespread racism and the tensions” that “pervaded the trial process for the soldiers making their trials unfair,” Sullivan said. It will also reflect the soldiers’ honorable discharges.

“I cannot even tell you that when the Under Secretary Camarillo made his announcement about the honorable discharges being restored or granted and that the descendants would get benefits, I don’t know about you, but I had tears in my eyes knowing that long though it may be, the arc of the moral universe still bends towards justice,” Green said.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- The top 10 Army unit patches from glider units to PSYOP

- Troops and veterans don’t like ‘Thank You For Your Service’ — so what’s better?

- Military officers used prostitution ring that checked IDs, credit cards, employers

- Fort Liberty soldier arrested, faces 34 counts of sex crimes against minors

- Did a stimulant known as ‘the drug of jihad’ fuel Hamas terror on Oct. 7?