The Army has a communications problem.

In at least three recent documented instances, the Army was either extremely reluctant to speak with the media on a high-profile issue, allegedly suppressed and withheld facts, and in one case provided blatantly false information. For this story, three active duty public affairs officers spoke on condition of anonymity in order to speak freely about issues they see in their field. They said the three instances are symptomatic of a larger problem: that commanders fail to recognize the importance of transparency, which results in an Army that doesn’t prioritize communicating with the public.

“The public affairs motto is strength through truth,” a field grade public affairs officer told Task & Purpose. “I think we need to remember that, and remember that we’re told that transparency is key to trust, whereas it seems like we prefer not to be transparent through fear.”

“We have a problem,” the officer said.

What the three officers described was an extremely risk-averse Army that often fails to proactively communicate — either from an outright refusal to do so, or from being weighed down by processes that force them to move too slowly, which is a frustration frequently voiced by reporters who work with the service. A seemingly simple question can sometimes result in days of waiting for a statement that doesn’t provide much context, or worse, one that says the Army won’t be commenting after all. (As one public affairs officer told me years ago, I could ask what color the sky is and even though we can all see the sky is blue, they’ll still need everyone and their lawyer to sign off on a statement confirming as much.)

A senior public affairs official said while the service has been aggressively focusing on modernizing everything in the force, that same forward-thinking hasn’t extended to the way it communicates. The Army has to modernize the way it communicates with the public, the official said, “otherwise, how do we maintain information advantage?”

The Army’s Chief of Public Affairs, Brig. Gen. Amy Johnston, said in a statement that Army public affairs professionals “respond to dozens of media requests” every day, and in every case “work to answer reporters’ questions with maximum disclosure and minimum delay.”

“Most of the time we get it right,” Johnston said. “But sometimes we fall short; regardless, we will strive to do our best, and continue to do so, no matter what the challenge.”

The Associated Press reported on Monday that the Army “sought to suppress information” regarding data on missing and stolen weapons. A former Army insider told the AP that Army officials “resisted releasing details” to the news organization when it started asking about the weapons 10 years ago.

In January, the Washington Post reported the Army “falsely denied for days” that Lt. Gen. Charles Flynn — the former Army deputy chief of staff for operations, plans, and training, and brother of retired Army Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn — was present during meetings at the Pentagon on Jan. 6, as riots at the U.S. Capitol began. Charles Flynn later confirmed to the Post himself that he was indeed present, which is not particularly surprising, considering Flynn’s job in the Pentagon at the time.

And in April, significant issues with Army public affairs were spotlighted in an internal investigation of Fort Hood’s involvement in and response to the disappearance of Spc. Vanessa Guillén. Fort Hood did not engage with the media on its own until May 21, almost 30 days after Guillén disappeared. According to the investigation, Maj. Gen. Scott Efflandt, the former deputy commander of Fort Hood, was encouraged to put his name on a press release which he refused, saying “he did not want to be ‘the face’ of the Guillén case ‘yet.’”

“The intent of the media release was to correct a narrative that the Army was not doing anything to find SPC Guillén,” the internal investigation said. But in many ways it was too late. By then, the narrative had taken off without the Army because of its reluctance to be proactive, which is something the field grade public affairs officer said happens frequently.

“Ignoring inquiries or questions online, it’s just a bad look and people assume the worst. If people assume the worst and you don’t say anything, that narrative is free to go … Army public affairs seems to delay the process of responding to queries so much that they are always playing from behind,” the officer said. Gen. John “Mike” Murray, who put together the investigation released this year, recommended that the Army’s head public affairs office “consider new policy and training on how to handle incidents” like Guillén’s disappearance and death.

The failure of public affairs at Fort Hood likely could have happened anywhere. Each of the three public affairs officers who spoke to Task & Purpose said a primary challenge in their field is commanders who are reluctant to publicly acknowledge wrongdoing and more inclined to believe if they don’t address something, it’ll eventually go away.

Rarely does it ever actually go away.

One of the officers who spoke with Task & Purpose recalled one instance in which they encouraged their commander to get out in front of a problem, only to have the commander say no because “he was very, very concerned about what his boss would say if there was a negative news story.”

“It’s very tricky to explain to them that ‘hey, if we don’t, it’s going to get worse.’ And then we’ll have dual issues, you’re creating a secondary problem being wrong and also not being transparent about the issue,” the officer said.

However, the officers also gave examples of commanders who communicate well; one pointed to U.S. Forces Korea, saying they’re “pretty much always really out in front of any problem.” They attributed that to the influence of the U.S Forces Korea commander, Gen. Robert Abrams. Another officer mentioned Brig. Gen. Milford Beagle, Jr., the commander of Fort Jackson, who put out statements regarding two separate racist incidents that involved current and former soldiers.

“The Fort Jackson [commanding general] was immediately open and honest about it … And that, I think, was the way to go, rather than kind of waiting to see what people are asking,” the officer said.

But that’s not always the case. The officers pointed back to the systemic issues in their field, like a lack of trust in public affairs and overwhelming red tape that slows down the process, and said oftentimes the Army simply doesn’t understand why proactively communicating with the public is important.

“I think it is fair to say the Army has a transparency problem, but not because they don’t want to [be transparent],” the senior official said. “It’s because they don’t know how to.”

“I don’t think they’re trying to deliberately deceive anybody,” the officer said, explaining that Army officials fail to understand how and when to communicate, which doesn’t exactly inspire confidence in the country’s largest military service to keep American taxpayers informed of what’s happening in the Army.

“They may think they’re making efforts for transparency,” the official added. “They’re not.”

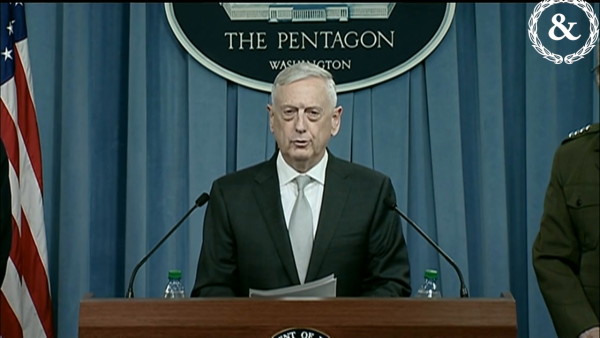

Featured photo: Lt. Gen. Pat White, III Corps and Fort Hood commanding general, addresses the media about the findings in the independent review and what is going to happen at Fort Hood moving forward. (U.S. Army/Staff Sgt. Daniel Herman)