Since 9/11, U.S. Army Special Forces have focused primarily on counterterrorism and foreign internal defense operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere around the world and are neither prepared to win in the current competitive environment nor the next major theater war. Counterterrorism and foreign internal defense requirements continue to shrink as the U.S. reduces its commitments to such operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere around the world, creating an opportunity for Special Forces to reorganize to better meet emerging threats.

Now with many decades of combined experience in Special Forces, we have deployed as detachment commanders, task force operational staff officers, and in many other operational command capacities to a myriad of different countries to rarely support anything other than counterterrorism or foreign internal defense missions. From Kidal in Northern Mali to Kunar Province in Afghanistan, and many places in between, we have served with and led America’s finest enabling partners and hunted down terrorists in some of the world’s most austere locales.

The Army has relied heavily on the 1st Special Forces Command (1st SFC) to conduct these operations, and as a result, its soldiers have become experts in counterterrorism and foreign internal defense. And yet, throughout these experiences, we have found Chinese, Russian, and other actors diligently pursuing their own national interests, quite oblivious to our efforts to rid the world of the scourge of terrorism.

It’s no surprise that the 2018 National Defense Strategy directed the Department of Defense to refocus its efforts on “great power competition” against near-peer global rivals, such as China and Russia. And it directed an increased emphasis on irregular warfare, or as the Joint Chiefs define it, “a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant population.” The Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy, recently published in an unclassified form by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict, directs an increased emphasis on unconventional warfare, a much-neglected Special Forces mission that directly supports irregular warfare. Revision of various geographic combatant command operational plans specifically call for the application of unconventional warfare capabilities to support irregular warfare in pre-conflict and conflict phases to deter and, if necessary, defeat Chinese and Russian aggression.

1st SFC has undertaken modest force management changes to adapt to this new focus, but the command has still not optimally configured itself to provide the unconventional warfare capabilities necessary to meet the irregular warfare requirements aligned with the NDS. One focus area of the Irregular Warfare Annex, referred to as “lines of effort,” directs the Defense Department to “[o]rganize the Department to preserve a baseline of IW knowledge, expertise, doctrine, and capabilities.”

This article provides force management recommendations meant to bring Special Forces “back to basics” and address this capability gap by ensuring optimal configuration of 1st SFC to develop formations designed to meet current and projected operational requirements.

Where is unconventional warfare going?

The majority of competition between the United States and its global competitors is occurring within the space known as “irregular warfare,” a critical activity of which is deemed “unconventional warfare.” The Department of Defense defines unconventional warfare as, “activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt or overthrow an occupying power or government by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary or guerrilla force in a denied area.” Enabling and directing an indigenous population to undermine and potentially replace an illegitimate government structure is the pinnacle of exerting national influence on the global stage.

1st SFC traces its lineage directly back to the men and women of the Office of Strategic Services, which was renowned for its “behind the lines” operations supporting various resistance movements against the Axis during World War II. In fact, the first Special Forces unit that was established in 1952 was comprised of several OSS veterans with an explicit mission “to infiltrate by land, sea or air, deep into enemy-occupied territory and organize the resistance/guerrilla potential to conduct Special Forces operations, with emphasis on guerrilla warfare.” While such activities will never singularly result in military victory, they can certainly contribute considerably to overall success. During both current peacetime competition and a potential wartime conflict with China or Russia, unconventional warfare-focused battalions would partner with local resistance forces to either deter enemy aggression from ever occurring or greatly increase the difficulty of with which an adversary could hold seized territory in the event of an actual invasion.

Although 1st SFC generally conducts counterterrorism and foreign internal defense in friendly territory in which they can operate freely and openly, its elements sometimes conduct unconventional warfare in enemy-controlled environments that require a far more sophisticated set of capabilities and skills to effectively execute this mission. Successful execution of unconventional warfare requires a myriad of advanced skills to effectively operate behind enemy lines to stealthily organize, train, equip, and advise indigenous personnel to conduct political resistance, support activities, and conduct hit-and-run combat operations against a superior enemy force.

During the Cold War until its deactivation in 1984, “Detachment A” was a small SF unit specifically tasked, trained, and equipped to conduct unconventional warfare and other highly sensitive operations. Unconventional warfare is the SF mission most closely aligned against those requirements that address the threat posed by near-peer adversaries like China and Russia.

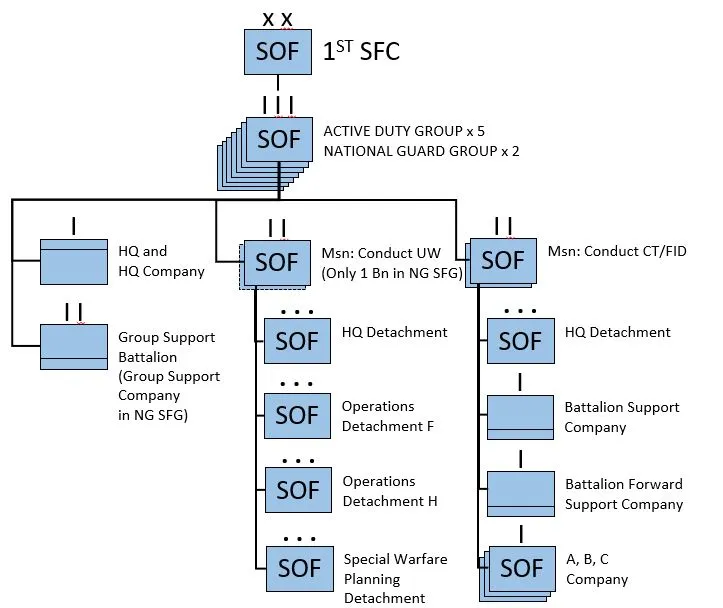

So how is 1st Special Forces Command currently organized? The command has five active-duty Special Forces Groups and two in the Army National Guard. Each of the active-duty groups (1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 10th Group) have three Special Forces battalions of soldiers focused on counterterrorism and foreign internal defense. Only one battalion is focused on unconventional warfare.

The two National Guard groups (19th and 20th Groups) have three counter-terrorism-focused battalions each and lack a dedicated unconventional warfare capability. Needless to say, the current force structure has produced a gap in special operations capabilities, despite repeated urging from Congress that U.S. Special Operations Command reduce its post-9/11 posture in favor of countering China and Russia.

Getting force structure right

Repurposing one battalion in each Special Forces Group to focus on unconventional warfare would better align the 1st Special Forces Command with the National Defense Strategy and its Irregular Warfare Annex while having minimal impact on readiness. The rest of the command’s organization would remain unchanged.

This would then result in having two battalions with expertise in counterterrorism and foreign internal defense, and two battalions ready for unconventional warfare missions. Meanwhile, National Guard Special Forces Groups would have two battalions remaining the same while converting one to unconventional warfare. Aside from this reorganization leading to better outcomes in line with national policy, this solution can be executed with existing resources: a battalion focused on unconventional warfare needs just 215 soldiers, while a counterterrorism/foreign internal defense battalion requires just over 509.

Once implemented, this conversion would reduce the 1st Special Forces Command’s total manning requirements by nearly 3,000 soldiers. This is particularly important given the much-lamented difficulty that all of special operations has experienced in recruiting enough new personnel to fill its manning requirements.

Still, we realize there will be pushback on this recommendation. The most likely area of contention would be in gaining buy-in from the rank-and-file, as stakeholders will point to the historically high demand for counterterrorism operations and partnering with foreign forces during the Global War on Terror. However, recent force realignment away from Iraq and Afghanistan will reduce those requirements and should make a refocus toward unconventional warfare priorities both more acceptable and necessary.

The devil is in the details

Several existing processes for managing personnel and their careers will require modification. Manning and training considerations will have the greatest impact on the successful conversion of one battalion per group to an unconventional warfare focus, as this recommendation requires the recruitment, management, and retention of exceptional personnel who are uniquely capable of operating safely in hostile territory for extended periods of time.

Still, a reorganization would reduce the overall manning requirements for the 1st Special Forces Command while eliminating the need for both battalion support and forward support company in each group.

There will be further challenges: While 1st Special Forces Command already has one of the most intensive assessment and selection processes in the military, the characteristics required for unconventional warfare further limits the pool of appropriate candidates. Additionally, the training required to develop true subject-matter experts capable of accomplishing such sensitive missions will strain the current pipeline designed to impart the required specialized skills. Implementation will only be successful if U.S. Special Operations Command increases its capacity to train unconventional warfare subject matter experts.

Finally, U.S. Special Operations Command must be willing to support the use of its increased unconventional warfare capability in those circumstances in which it is both appropriate and able to contribute meaningfully to broader national interests. In interagency discussions, the Defense Department’s Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict plays a critical role in advocating for the development, maintenance, and employment of unconventional warfare options as the “service-like secretary” for the U.S. Special Operations Command.

Historically, other departments and agencies within the U.S. government have resisted the Defense Department’s efforts to apply indirect military approaches against sensitive international security challenges. Within a broader irregular warfare framework, the Defense Department can and should nest more robust and aggressive unconventional warfare activities to fully support interagency approaches to our thorniest problems.

The performance of the 1st Special Forces Command since 9/11 has been nothing short of extraordinary, as soldiers have bravely served on the frontlines around the world. But to win the next fight, on the next battlefield against peer competitors, it is imperative that the command be ready, willing, and able to execute the unconventional warfare mission.

Our proposal would create Special Forces formations with the capabilities necessary to counter China and Russia while getting back to the fundamental ideal of what makes Special Forces truly “special.”

It would create a Special Forces Command that is more reflective of its roots — more closely resembling the famed OSS and early Army Green Berets that stood up against Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and other communist adversaries throughout the Cold War. Finally, it would model those Special Forces “Horse Soldiers” who waged unconventional warfare to fight alongside the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan to bring about the rapid collapse of the Taliban in 2001.

This return “back to basics” will certainly require considered and sustained focus throughout the Department of Defense and the Army to successfully transform 1st SFC into a formation even better prepared to meet the nation’s current and future operational requirements and meet the threat posed by China and Russia. However, the modest investment made now, during a period of reduced counterterrorism threats, will allow the force to better support the National Defense Strategy and Irregular Warfare Annex.

A refocus on increased unconventional warfare capability will both allow for greater deterrence to prevent a war with China and Russia or, failing that, provide the United States and its allies with the means to drastically increase the cost and difficulty by which adversaries might pursue such aggression.

As President John F. Kennedy said in 1962, “There is another type of warfare — new in its intensity, ancient in its origin — war by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins; war by ambush instead of by combat, by infiltration instead of aggression, seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy instead of engaging him,” he said, his words still applicable to today’s challenges. “It preys on unrest.”

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government. The public release clearance of this publication by the Department of Defense does not imply Department of Defense endorsement or factual accuracy of the material.