The U.S. military’s vaunted hypervelocity projectile just took a major step towards knocking incoming cruise missiles out of the sky.

Breaking Defense reports that the Air Force recently used the HVP — a low-drag, guided projectile capable of reaching speeds up to Mach 5 — to down a BQM-167 target drone over the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

The BQM-167 drone “served as surrogates for Russian cruise missiles” during a demonstration of the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System that’s designed to enable the rapid detection and destruction of incoming missiles.

The HVP was fired from an Army M109 Paladin-based 155mm howitzer and a Navy deck gun during the demonstration, according to Breaking Defense.

“Tanks shooting down cruise missiles is awesome,” Dr. Will Roper, assistant secretary of the Air Force for acquisition, technology, and logistics, told reporters. “Video game, sci-fi awesome.”

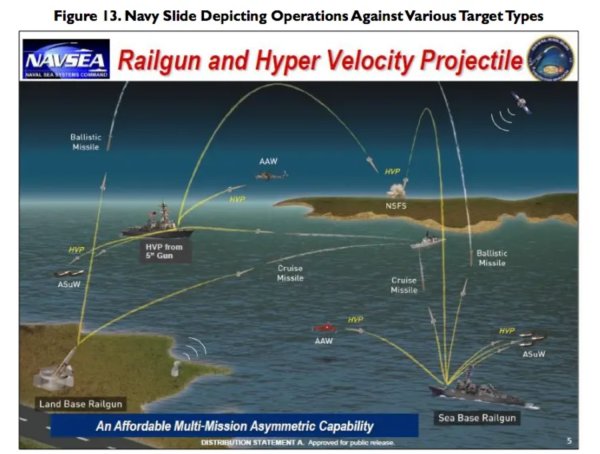

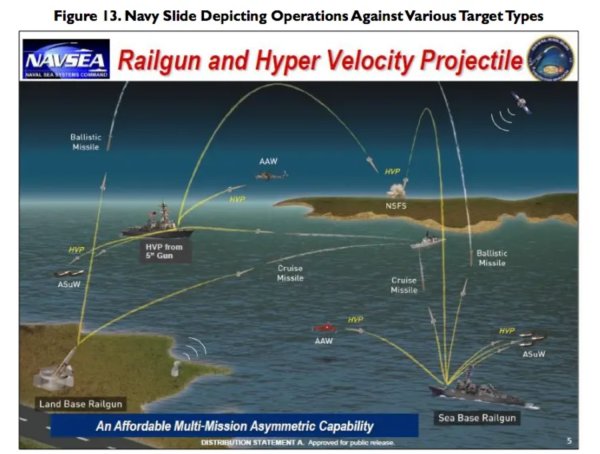

Originally developed starting in 2013 as specialized ammo for the Navy’s much-hyped (and decidedly stagnant) electromagnetic railgun, the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO) has since transitioned the HVP for use from conventional powder weapons like Army howitzers and Navy deck guns.

In 2018, the Navy reportedly test-fired 20 next-generation HVP shells from the USS Dewey’s Mk 45 five-inch deck guns during the service’s annual Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) maritime exercise.

The advantage of the HVP over conventional missile defenses is a matter of cost: While the standard Evolved Seasparrow Missile or Rolling Airframe Missile cost several million dollars apiece, HVP program manager Vincent Sabio pegged the cost of an HVP at around $85,000 apiece.

The same logic applies to the standard Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) interceptors that fill mobile THAAD batteries around the world, Sabio added.

“Our finger pauses over the fire button just because we know every time we push it we’re pushing a fair amount of money out of that launcher,” he said of the Patriot. But with HVPs, “You can shoot a lot of those things and not feel badly about it.”

And while the DoD’s existing land- and sea-based interceptor vehicles perform fine against ballistic missiles, they don’t offer an optimal chance of success against incoming cruise missiles or hypersonic weapons which have become a major focus for the China and Russian militaries — and, in turn, necessitated a similar technological response from the Pentagon.

“We need to be able to address (all) types of threats: subsonic, supersonic; sea-skimming, land-hugging; coming in from above and dropping down on top of us,” Sabio said at the time. “There are many different trajectories that we need to be able to deal with that we… cannot deal with effectively today.”

Related: The Navy’s $500 million effort to develop a futuristic railgun is going nowhere fast