The text arrived on Tech Sgt. Kyle Olson’s phone late on a Friday afternoon.

“26 YOM head injury, struck in head by metal pole,” the text read. “Blood loss, in/out of consciousness. 2000 nm away,” the shorthand for ‘nautical miles.’ “130s are determining if they can make it in a day.”

Olson understood immediately: somewhere in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a 26-year-old sailor was in critical condition and the 129th Rescue Wing was going to go get him.

At the bottom were instructions on how Olson should reply:

“1) available for [take-off] early tomorrow Saturday 8 July.

“2) not available.”

Olson texted back:

“1”

“They take a look at who is available for what roles and they put together the team,” said Olson, a California Air National Guard pararescueman, or PJ, with the 131st Rescue Squadron. The 131st is the 129th wing’s home for several dozen PJs who train and deploy for both combat and local civilian rescue missions.

Word soon came back: Olson was on the team for what was shaping up to be a high-risk mission, even by Air Force PJ standards.

The 131st team planned to parachute from one of the 129th wing’s HC-130J — the ‘130’ in the text — to reach the fishing boat, 750 miles out in the Pacific Ocean from the coast of Costa Rica.

There were no nearby vessels and no other planes that could help. Once the four men stepped off the rear of the aircraft, they would be totally alone, with no retreat, no support, and no backup if something went wrong.

Adding to the risk, the team’s jump would be at night.

Mid-ocean parachute jumps are extremely rare and among the most high-risk missions a U.S. military unit can be asked to perform inside the U.S. But if any unit can claim to be an expert in pulling them off, it’s the San Jose-based 129th Rescue Wing. Based at Moffett Field in the heart of silicon valley, the team has executed more than half of the dozen or so open ocean rescue jumps performed by Air Force and Air Guard units since 2010.

“We take maritime training very seriously because it’s one of our most likely calls we’ll be tasked with,” Olson told Task & Purpose a few days after returning from Costa Rica.

Among those missions were similar jumps to rescue injured sailors in August 2022 and August 2015 and a jump in 2014 to aid a family on a sailboat whose 1-year-old daughter had become sick and badly dehydrated.

The Costa Rica mission, though, was one of the farthest from home in the unit’s history.

According to Olson, the PJs used a phalanx of specialized training, skills, and custom-made equipment unique to pararescue teams, along with some not-so-specialized gear like common iPhone apps throughout the three-day mission. When the team stepped off the rear of their plane, the jumpers were loaded down with enough medical equipment to outfit a full-sized city ambulance and were accompanied by a rubber raiding craft rigged with its own parachute. On the ship, they stayed awake for most of the three days, treating the sailor with advanced medications rarely found outside of hospital emergency rooms.

And to get home, they executed two mid-ocean ship-to-ship transfers, dangling with their patient over the open ocean on hastily rigged ropes and cables.

None of this would have happened without the initial call for help.

Assembling the rescue team

Few offices in the US military oversee a larger slice of the earth than the Coast Guard’s Eleventh District Command Center in Alameda, California. The 11th District keeps watch across 74 million square miles of the Pacific Ocean, from Arctic waters to South America.

The call from Costa Rica reached the 11th a little after 9 a.m. on July 7. A crew member of a fishing trawler, the Virginia A, had been hit in the head by a swinging pipe while nearly 1,000 miles from shore.

Almost immediately, officials realized it fit the bill for a possible PJ jump mission. The ship was far beyond the 300 miles at which rescue officials begin to consider a parachute jump, and there was no doctor or medic onboard. His condition seemed to be deteriorating, which made time a critical factor.

With that, officials made a call across the San Francisco Bay to Moffett Federal Airfield and the 129th.

The 129th is one of a handful of Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve rescue units across the country at bases in Anchorage, Alaska, Portland, Oregon, Cocoa Beach, Florida, Tuscon, Arizona, and on Long Island in New York. The units are split into squadrons of HH-60 helicopters, HC-130 tankers, and pararescue teams.

Many of the aircrew and PJs on the teams have full-time civilian jobs: PJs are often firefighters or hold civilian jobs in the medical field, while many of the helicopter and tanker pilots work for airlines. Though all can deploy as combat rescue units, the PJs and aircrews relish the chance to respond to civilian emergencies closer to home.

By early evening on July 7, 129th officials had their team in place. Olson would be the senior of three medics on the jump team, with Sr. Airman Spencer and Staff Sgt. Keith, who asked that only their first names be used in this story. The team leader was Tech. Sgt. Chris Rosengarten, who, Olson said, was the only PJ of the four with a jump mission already under his belt.

“It was a pretty green team,” Olson said.

The astronaut rescue system

At the heart of every PJ ocean rescue is a gear package that shares its name with an 80s action hero: the “Rambo.”

In the 1980s, in the wake of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, NASA investigators made a gruesome realization: the explosion that destroyed the shuttle may have been survivable to the crew, but they had no hope of bailing out, parachuting, or otherwise surviving once the shuttle broke apart high in the atmosphere. In response, NASA redesigned the crew cabin to have escape equipment that, hypothetically, astronauts could use to bail out of a doomed orbiter.

This led to a new problem: once they bailed out far over the ocean, who was going to get them? NASA tasked the Air Force’s rescue community to figure that part out.

In response, PJ teams folded a full-size rubber raiding boat into a five-foot cube topped with parachutes, a system now called the Rigging Alternate Method-Boat (RAMB — pronounced RAMBO like the Sylvester Stallone movie). The system could be rolled from the rear of a cargo aircraft like the HC-130 tankers that all Air Force rescue units fly.

From the late 1980s to the end of the Space Shuttle program in 2011, close to two dozen PJs with RAMBs were on alert at remote airfields on both sides of the Atlantic for every launch.

After loading Friday night, the 129th crews went home, with a plan to launch Saturday morning, July 8. It would be a long day.

Warm water and lots of gear

The crew flew from San Jose to Mexico City for fuel, then out to sea toward the last known coordinates of the boat. In flight, the PJs unpacked and sorted the boxes of gear they’d brought, deciding what to jump with and what to leave behind. One member tried on a dry diving suit but then came a report on sea conditions.

“The water temperature was around 86 degrees,” said Olson. “No wetsuit needed.”

The team would jump in rugged, insulated pants made by Crye, and a blue long-sleeve t-shirt. More important was what medical gear they would take and how.

Ocean missions often involve gruesome medical conditions, with burns from fires or serious injuries from heavy machines and equipment. But PJs, who train as special operations combat medics, are well versed in such trauma. But the Costa Rican sailor had been struck in the head, which could mean a traumatic brain injury, or TBI, a notoriously difficult condition to treat outside of a hospital.

The team needed a slew of narcotics, which are easily carried in a small pouch, but also bulky, heavy medical equipment: two oxygen bottles, an advanced heart monitor, and even a ventilator — plus several bags of specialized IV fluid used specifically for TBI.

On top of that, the team carried a full pararescue medical kit in a rucksack, and each PJ carried enough food and water for 72 hours.

They packed everything into oversized, waterproof bags they could attach — barely — to their parachute harness.

“If for some reason the boat burned in, or you couldn’t get to the boat, at least everyone has what they need and [the orbiting HC-130] can always throw the second boat out,” said Olson. “Or the boat you’re jumping to could come pick you up” — here Olson paused to consider such a scenario, being saved from the sea by the crew they were sent to ‘rescue’ — “which would be embarrassing but that’s how it goes.”

The jump

The team had hoped to jump during daylight, but as the HC-130 raced into the Pacific in the late afternoon on July 8, it was clear they would not reach the ship until nightfall — making the jump significantly more risky. As the PJs sorted and packed their gear, the plane’s loadmasters began loading illumination flares into the plane’s tail.

“By the time we were overhead you couldn’t see anything,” said Olson. Fortunately, the Virginia A. had its full suite of deck lights on. “You couldn’t miss it.”

As they circled the boat, Tech. Sgt. Jose Arceo, a 129th tactical aircraft maintenance specialist, was speaking in Spanish with the Virginia A.’s captain. Arceo had joined the mission specifically as a translator.

The patient was deteriorating, and there was no aid for him on the small fishing boat.

The jump was on.

A fifth PJ, Tech. Sgt. Tammer Barkouki was on board as the team’s jumpmaster. Though he would not jump, once the go-ahead came through, he began running through final gear checks and asking Arceo to quiz the ship about surface winds.

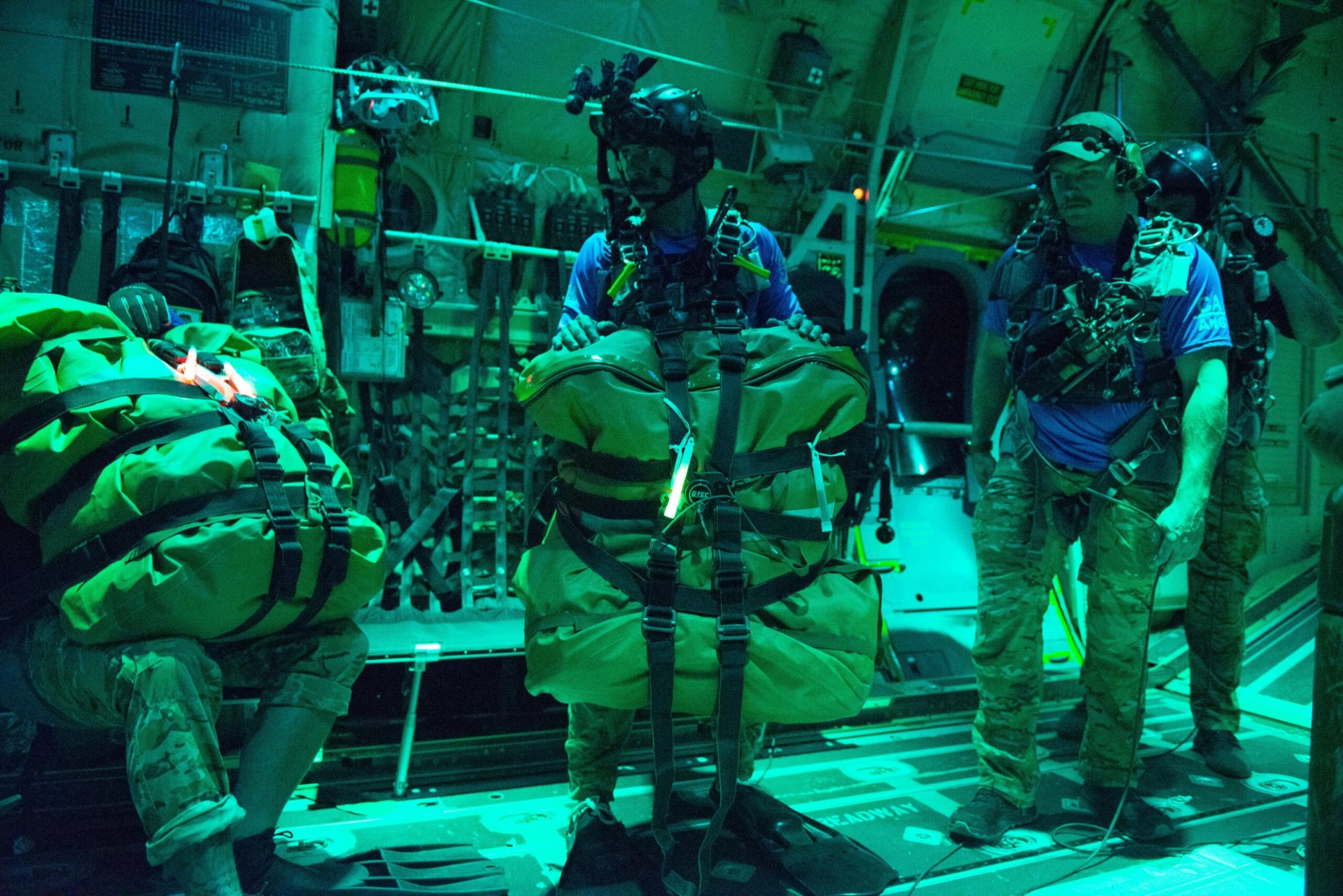

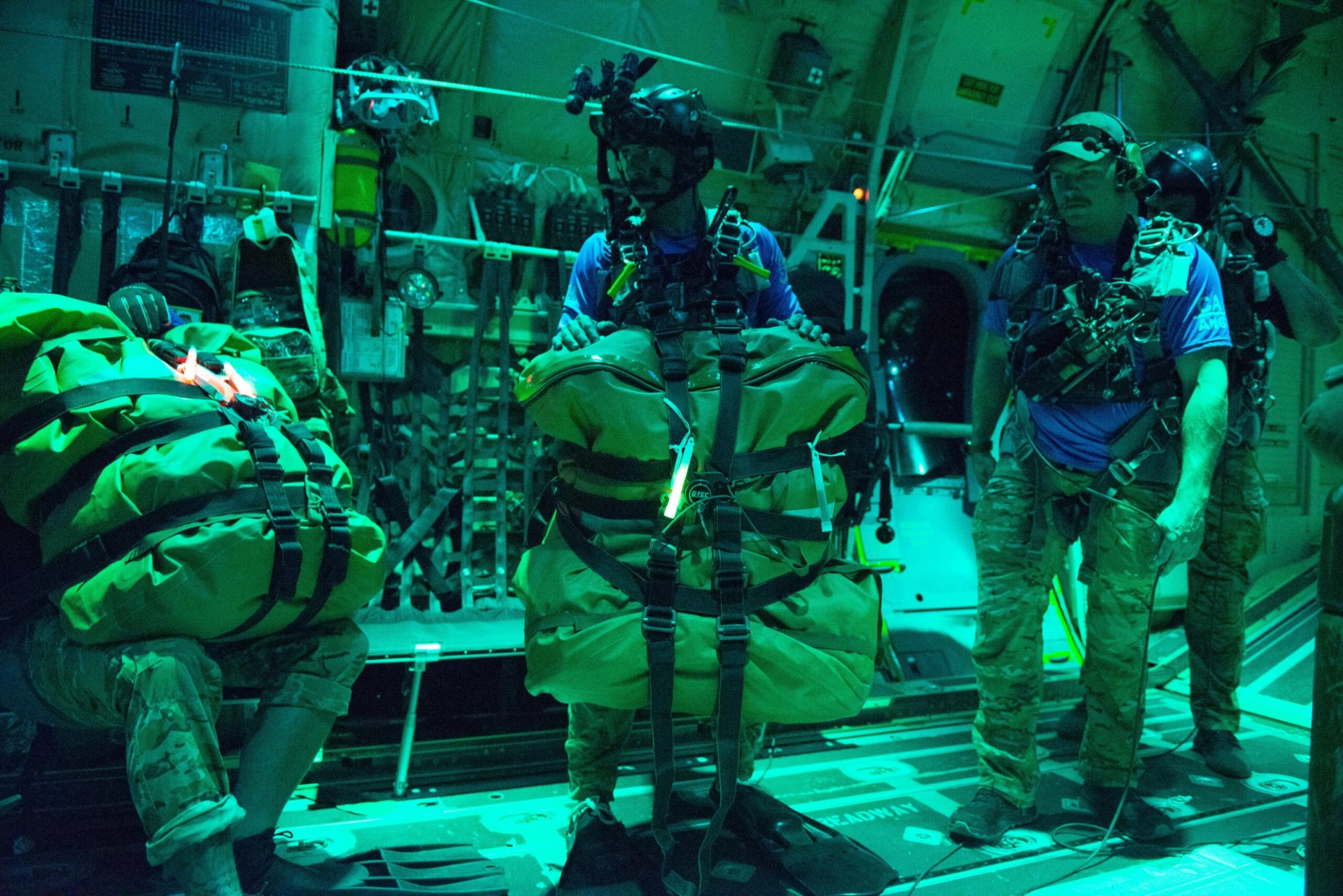

Barkouki snapped the chem lights attached to the RAMB and on each jumper — green on the rear, red on the front. The glow sticks are a simple way for each jumper to know — even in pitch black — if they are safely following a teammate in the air — green — or if they are headed for a mid-air collision — red.

Along with the huge packs that stretched from their faces to their knees, the PJs wore heavy swim fins on their feet and had snorkels and goggles awkwardly hanging from their helmets. In all, each jumper wore close to 100 pounds of gear and could hardly do more than stumble and waddle to the rear of the HC-130 as Barkouki gave final directions.

On the final pass, with the HC-130’s interior lights turned to green and the wind howling over the open ramp, Barkouki gave the jumpmaster the sign to push the RAMB out. It rumbled off the cargo tracks and snapped open almost immediately as its parachutes caught wind, disappearing into the darkness.

Then he looked at the team and pointed out the ramp: go!

With Rosengarten at the front, the PJs waddled single-file the last few feet off the ramp, jumping in a “squat” one at a time, falling into the night, waiting the two or three eternal seconds to feel their parachute snap open above them.

“It was definitely the darkest jump I’ve ever done,” said Olson.

The patient

The darkness wouldn’t last. As soon as the jumpers were under canopy, the HC-130 crew fired flares, illuminating the night sky and turning night to day.

“Everyone landed pretty close,” Olson said. In the water, the team swam quickly to the RAMB. Once the boat was inflated, they sped toward the Virginia A and climbed aboard.

Immediately, they broke out a key piece of gear: the iPhones.

“We all jumped in our phones and used Google translate to communicate with the crew the whole way,” said Olson. “We made sure it was downloaded so it works out there where there’s no signal.”

They found the man awkwardly arranged on the tiny cabin’s galley table.

Their plan, Olson said, was to work the patient in two-hour shifts while other team members slept.

“Didn’t work out that way. We were all pretty much up the whole night,” Olson said.

TBI treatment is well known to modern military medics and pararescuemen follow a specific protocol for it. They first positioned the man with his head up close to 30 degrees, gave him oxygen through a mask, and did a quick neurological exam to determine how awake and oriented, or “A&O,” he was on a scale of 1 to 4. Fully alert and aware is a 4, and a 1 is highly disoriented. “He was A&O times 2, maybe 3,” said Olson.

They started an IV, replacing the normal saline fluid — which is less than 1% sodium chloride — with a solution that is 23.4%, a hyper-salty mix that pulls fluid from body tissues, relieving swelling.

Finally, they considered what medicine they might use to stave off seizures, a common late symptom of severe TBI. They carried Keppra, an anti-seizure drug, and Midazolam, a sedative. If things got really bad, the PJs also carried Ketamine, a dissociative sedative so powerful it is often used to put patients under for surgery, though it has migrated to field rescue work in recent years.

As the team treated the sailor, he quickly stabilized and continued to improve for the remainder of the mission. “No close calls,” Olson said.

All that was left to do was get home.

Transfer and back home

By the middle of the next day, the Virginia A. rendezvoused with a large freighter that would take the team to shore. But that meant switching boats on the open sea, a moment that was almost certainly the riskiest and most improvised of the mission — or, as Olson remembered it, “super dangerous.”

As the ships steamed next to each other, they would use their cranes to bring the team across with the patient packaged in a flexible sled known as a skedco. The PJs also gave the man another dose of ketamine, Olson said, to keep him from, well, freaking out as he helplessly dangled over the open water.

Keith rode with the sailor as the “barrelman” tied to the patient, ensuring he did not get hung up, flipped upside down, or otherwise became injured during the transfer.

Still, said Olson, it was a sketchy event.

“Depending on the sea state, and how good the drivers are and their overall communication, it’s super dangerous,” Olson said. “If one thing goes wrong, it’s just a compounding effect and a whole bunch of things go wrong.”

But after a few tense moments dangling over the Pacific, the team was aboard the freighter.

On the far more spacious ship, the PJs set up an improvised hospital room and for the next two days continued to treat the man and, finally, got some sleep.

After a second transfer to a Costa Rican coast guard ship closer to shore, the team arrived in port about three days after they’d stepped off the HC-130’s ramp.

That night, said Olsen, the team and the aircrew — which had been in Costa Rica since the jump — hit a local bar to celebrate. They were met by a former 129th PJ who drove five hours from where he now lives during the summer in Costa Rica. The crew had dinner and celebrated the mission, said Olson, but after the three-day mission, were too tired to overdo it.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Air Force shows off its Rapid Dragon cruise missile system on China’s doorstep

- The Pentagon didn’t refuse to pay $60,000 to fly fallen Marine Nicole Gee to Arlington [Updated]

- Bowe Bergdahl’s court-martial is overturned

- Everything we know about the U.S. Army soldier in North Korea

- Parris Island drill instructor found not guilty of Marine’s death during Crucible