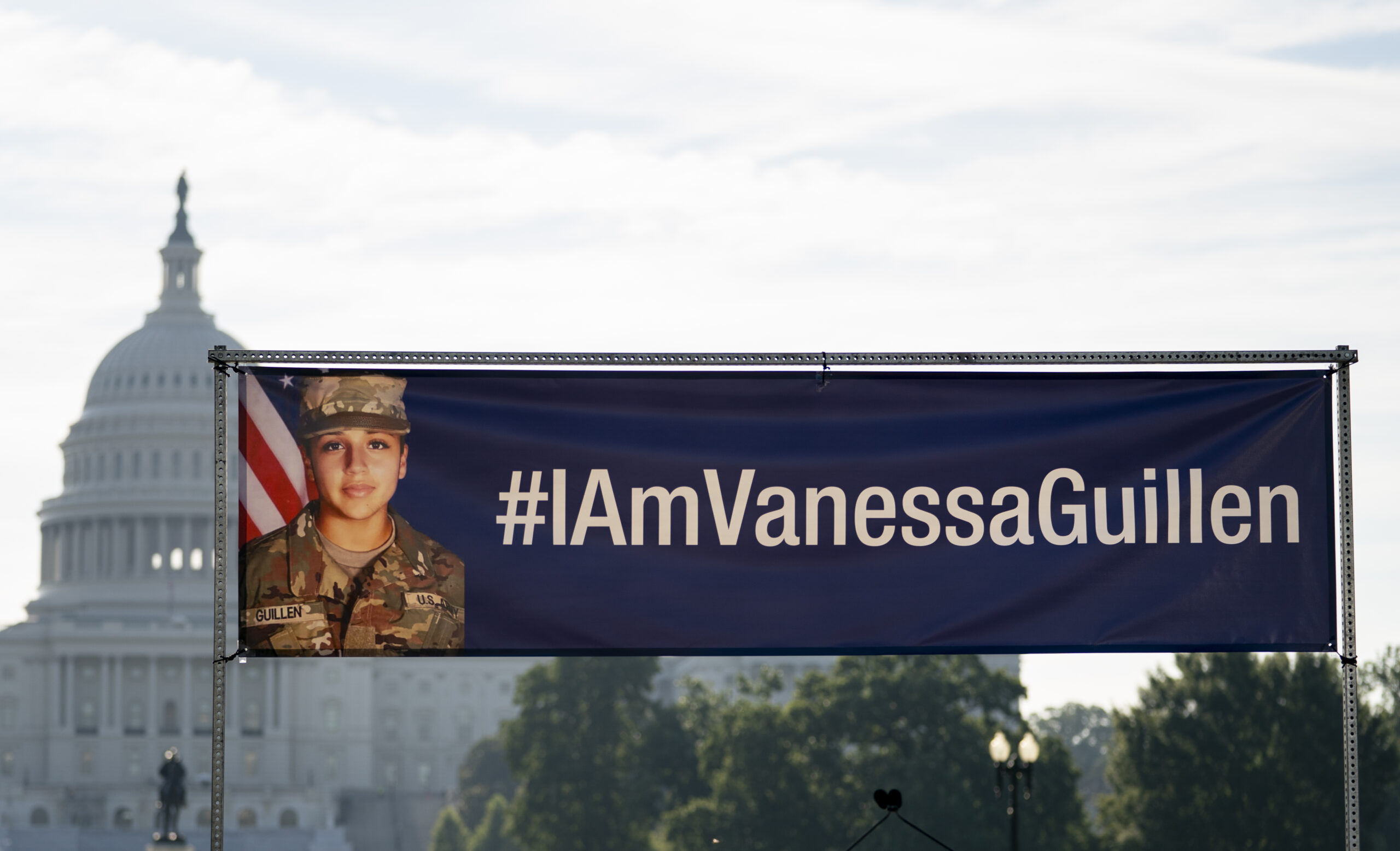

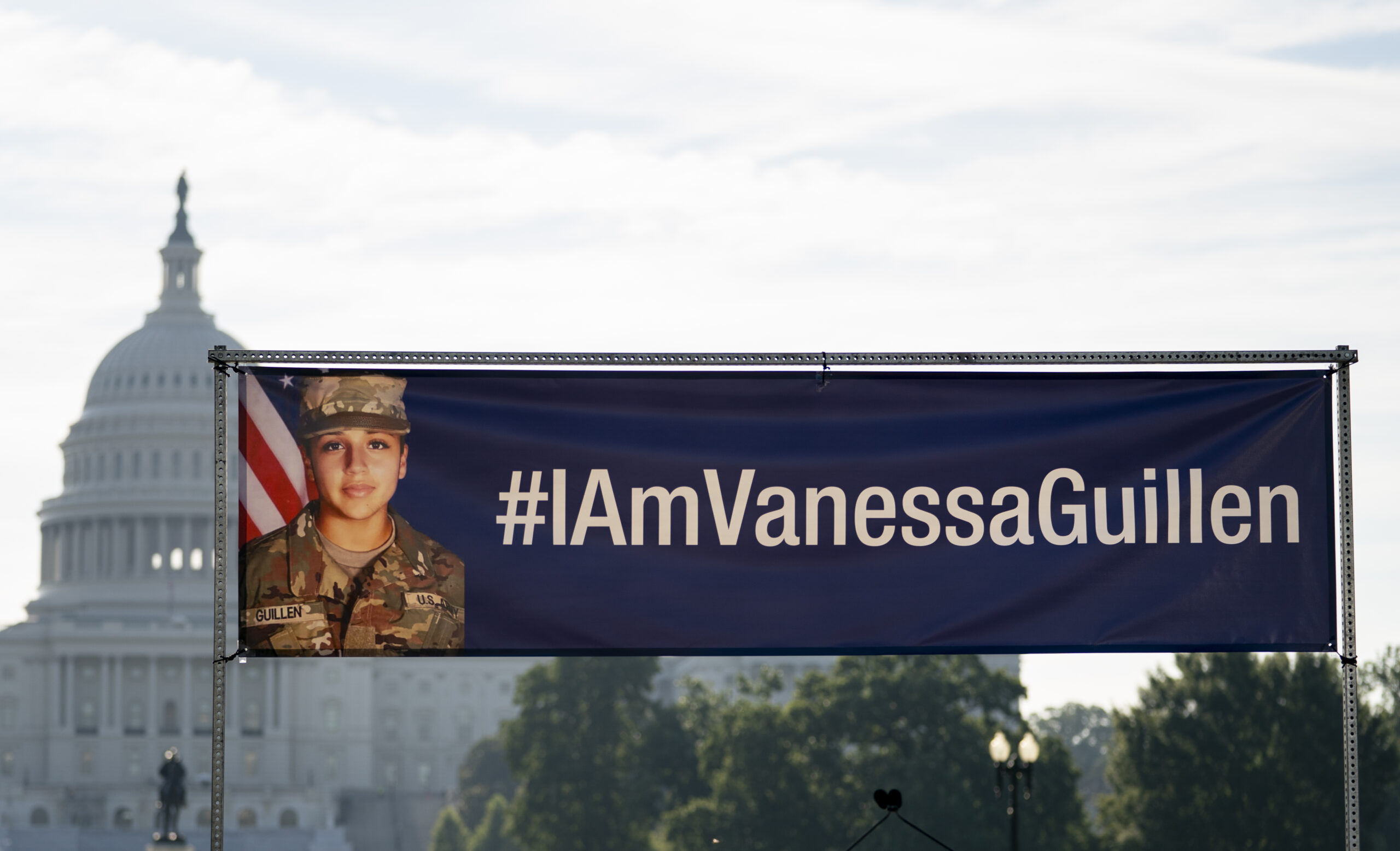

An independent civilian panel’s review of Fort Hood has uncovered shocking lapses in the investigation of Army Spc.Vanessa Guillén’s death that are emblematic of the inexperienced special investigators at the base who often make rookie mistakes.

The Fort Hood Independent Review Committee found that out of 35 Army Criminal Investigation Command special agents who look into cases at Fort Hood, only three special agents have more than two years of experience, according to the panel’s report, which was released on Tuesday.

In fact, a total of 58 of the 63 special agents who were assigned to Fort Hood in fiscal 2019 were fresh out of CID’s 16-week training course, even though the base has the highest drug test failure rate of all divisional posts: It is more than 30% higher than divisional posts and 151.7% higher than-divisional posts in the United States, the report says.

“It has been the experience of these career federal law enforcement professionals that investigative agents with less than 2 years’ experience are generally only capable of conducting simple witness interviews, handling less complex investigative techniques and acting in a support role for more experienced case agents,” the report says.

The investigators’ lack of experience was on full display when Guillén disappeared in April, according to the report.

The special agents “conducted brief, choppy interviews of key individuals” in the critical early stages of the investigation, the report says. They also did not include contact information for the witnesses interviewed or indicate whether they had spoken to people by phone or in person.

“The interviews appeared to be rote and indeed checklist driven,” the report says.

Communication between special agents was extremely limited, according to the report.

On April 24, one agent learned that Guillén met with Army Spc. Aaron Robinson — the soldier accused of killing her — in his unit’s arms room on the day she disappeared, according to the report. Another special agent learned that Guillén had texted Robinson.

Yet there are no indications that a third special agent who interviewed Robinson that evening tried to look at Robinson’s phone or take the device into custody to preserve Guillén’s text and other evidence, the panel found.

CID special agents also believed three noncommissioned officers, who said they saw Guillén leave the arms room and walk toward the parking lot even though none of the soldiers were in Guillén’s unit or knew her. They also provided conflicting descriptions of what Guillén was supposedly wearing, but they were not pressed for details until much later in the investigation, by which time they had changed their stories.

“As a result, CID Agents did not consider SPC Robinson of sufficient interest to even examine his phone, subject him to a more intense investigative focus and at least a more intense and detailed interview by an experienced Special Agent,” the panel found.

CID also did not advise Guillén’s unit to change her duty status from absent without leave even though her keys, wallet, and Common Access Card were found in the squadron headquarters arms room; her car was still in the parking lot across from the street from her barracks; all financial activity on her bank and credit accounts had ceased; and, most importantly, she never returned from what was supposed to be a very brief visit with Robinson in another arms room, according to the panel.

The panel determined that the Fort Hood CID office was receiving “almost no guidance and minimal support” from its battalion leadership.

“In fact, during the Vanessa Guillén investigation, guidance and resource assistance from the Battalion was nonexistent until [Maj. Gen. Scott L.] Efflandt inquired into whether the CID had sufficient resources and expertise,” the report says. “After that inquiry, the CID Office finally obtained some much needed assistance in the form of temporary duty Special Agents, electronic evidence forensics, analysis of electronic evidence, and drafting of probable cause affidavits to support warrants.”

To wit: the inexperienced special agents had such a hard time writing warrants that they ended up needing help from CID headquarters in Quantico, Virginia, the Texas Rangers, and other federal agencies to articulate how they had probable cause to secure evidence, the report says.

“In the Guillén case there were two instances where the incorrect information led to fruitless searches and expenditure of scarce manpower,” the report says.

The amateur hour investigation skills were not limited to the Guillén case, according to the report. A review of Fort Hood investigations from fiscals 2018 to 2020 revealed a stunning lack of competence.

In one 2018 investigation into the death of an infant, a man initially lied by saying the child had struck his head before ultimately admitting that he had shaken the baby to death.

“Autopsy results stated the death was a homicide, however a referral was not documented in the file as of the time of this Review,” the report says. “Moreover, the subject was allowed to stay in the barracks while the case was investigated for 18 months, with no apparent evaluation of the risk the subject posed to himself or others.”