A U.S. Marine and his family have been stuck with a $14,000 bill from a private military housing company, and they are worried others could face similar burdens even if they have renters insurance.

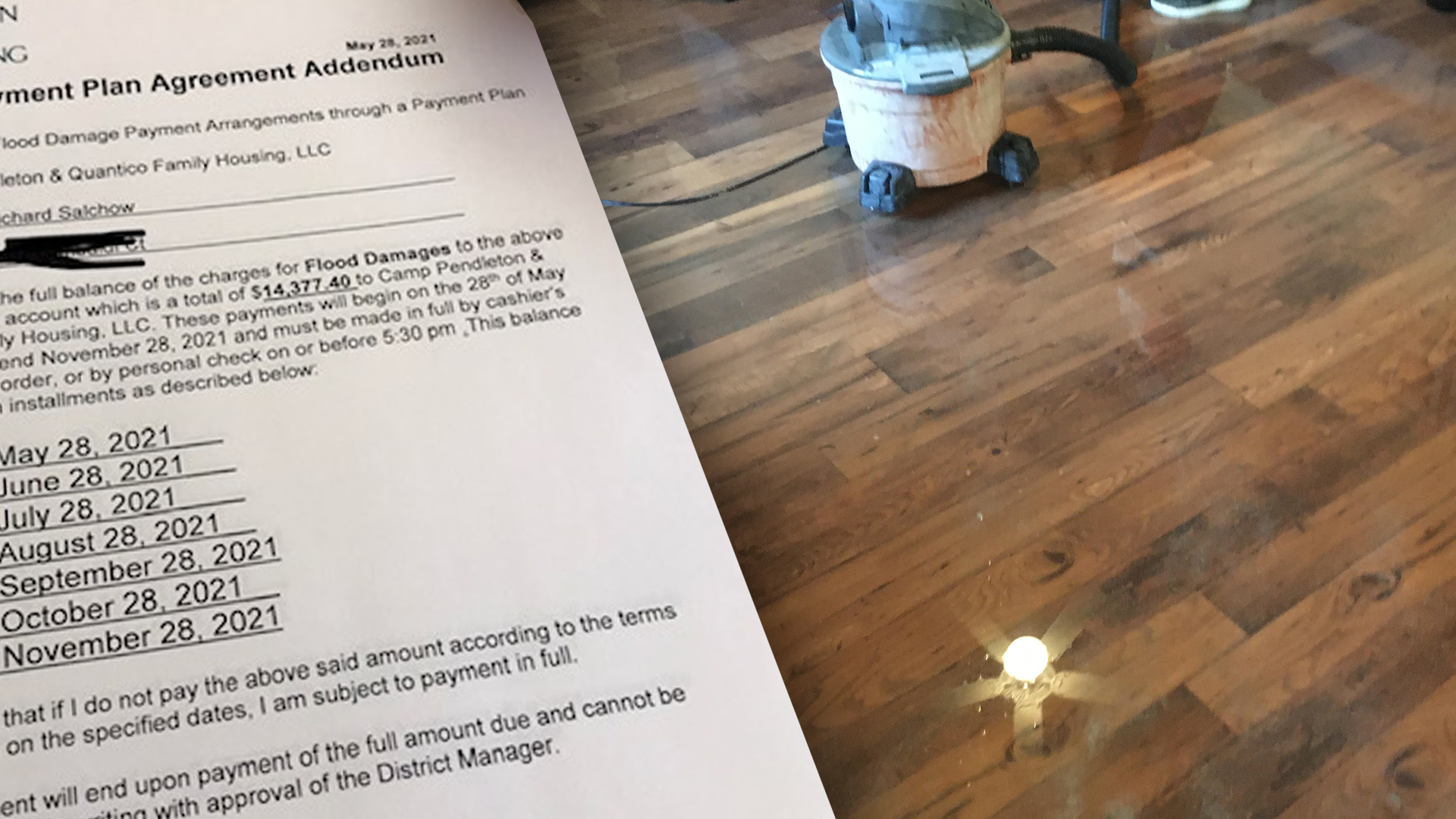

Maj. Richard Salchow and his wife Colleen had been away from their home at Camp Pendleton, California for about five hours on January 16 when they returned to find their floors flooded. Their washing machine malfunctioned during a load while they were out and left a quarter-inch of water covering the entire first floor.

They immediately started vacuuming up the water and contacted their landlord, Lincoln Military Housing, to report the issue, but by then it was too late: The valve between the washer and the water supply had broken and sent so much water leaking throughout the house that it affected the drywall and led to bubbles under the linoleum floors.

“I didn’t even know what a water valve was until I had a repair technician come out,” Richard said.

Lincoln, which owns more than 6,000 homes on the coastal Marine base, secured temporary lodging for the couple within a few hours. And the Salchows were confident things would be taken care of promptly considering the company had outright replaced a faulty dishwasher, stove, and refrigerator in the past. “Anytime you call them they fix it,” Colleen said.

Fortunately, repairs began by January 21 and the couple was able to move back in before the end of the month. But Lincoln said they’d have to file a liability claim for the flooding since it was caused by a washer owned by the family.

“I thought okay we’re good because we have a $100,000 liability policy so there’s no way the repairs could be more than $100,000,” said Richard, a logistics officer with the 1st Marine Division who has served for over 11 years.

He asked Lincoln for work invoices and began reaching out to his insurance company USAA. Their renters insurance policy documents said damage to base housing was covered as long as he was on active duty at the time and the house was “government-controlled.”

Yet that was the problem. An out-of-control load of laundry led to repairs totaling $14.377.40 in base housing but the Salchows, like many military families these days, lived in what’s called a public-private venture: The federal government owned the land but the house itself was leased by a private company which then rented to service members in exchange for their military housing allowance.

“The home you rent from Lincoln Military Housing is not considered to be Government housing,” a USAA representative told Richard in February, according to a provided transcript. “While Lincoln and many other entities are located on bases, they are companies which contract with the Government to lease the land, build residences and manage the facilities. … As the location where you live is not considered Government Housing, that provision does not apply.”

A USAA official declined to comment on the specifics of the Salchows’ case, but said the company offers renters insurance that covers damage caused by water.

“USAA is well known for providing outstanding claims service to our members. While we cannot speak to the specifics of this claim, a standard renters policy intends to provide coverage for the insured’s personal property and limited liability,” said Rebekah Nelson, a USAA spokesperson, noting the USAA website had information on what is and is not covered. She could not point to a specific insurance product that could have helped the Salchows or others, however.

“I asked the USAA insurance adjustor if I could have elected additional coverage for our policy and he indicated that I did not decline any coverage,” Richard said. “We purchased the full renter’s insurance policy from USAA, with liability.”

Still, USAA was able to give them $1,000 as part of its “good neighbor policy.” And though Richard brought the issue up to his chain of command, there wasn’t much his fellow Marines could do to help in the confusing world of privatized military housing, insurance, and leasing documents. “Am I just not understanding this correctly?” Richard wondered.

He also tried negotiating with the base housing office, which initially scheduled a meeting to discuss the issue on a day Richard could not attend since he was training hundreds of miles away in Twentynine Palms, California. The family finally met on April 19 with housing director Robert Marshall, according to email records, though Richard said he didn’t hear anything more from Marshall until more than a month later despite making several attempts to contact him.

“I thought that there would be some sort of informal resolution to minimize that bill as much as possible,” Richard said. Instead, the Salchows said at one point they were told by a Lincoln representative that they should consider letting the bill go to collections where a deal could probably be cut to lower the cost.

“That’s horrible advice to give to anybody,” said Colleen, who has a financial education background and knows issues like these can negatively affect military security clearances and credit scores. “It just felt like a punch to the gut.”

Lincoln Military Housing spokesperson Ashley Gorski Poole declined to comment on the Salchows’ case, citing residents’ privacy, but said in a statement that “although the Department of Defense eliminated the renter’s insurance component of the Basic Allowance for Housing in 2015, Lincoln Military Housing continues to provide renter’s insurance to residents of the Camp Pendleton military housing community through 2021 for personal property contents coverage. However, the insurance provided is not and was never intended to be a substitute for a proper renter’s insurance policy, including liability coverage.

“We understand that unforeseen circumstances can occur,” Poole said, adding that Lincoln and its military partners have encouraged families to have renters insurance at “multiple touchpoints,” including a “plain language briefing” prior to residents moving in.

The commanding general and other Marine leaders at Camp Pendleton have taken notice of the Salchows case. A friend close to the family recently wrote about their predicament in a Facebook group for Marine officer spouses, warning that Lincoln Military Housing “seems to have a $50,000 deductible, at least on some houses at [Camp Pendleton]. So if something belongs to you in your house [and] causes damage to their property, you can end up owing up to $50,000 in damages.”

Brig. Gen. Daniel Conley “has monitored and directed the advocacy efforts of the Military Housing Office and ordered an information campaign about renters insurance as a way to protect against unforeseen circumstances caused by environmental or user-related incidents that damage either the person’s belongings or the physical property itself,” said 1st Lt. Charlotte Dennis, a base spokesperson.

There is not much Conley or anyone else can or will do about the Salchows’ bill beyond that.

“I can honestly see no way we could have possibly planned for this scenario,” Colleen said of the situation in the Facebook post.

Dennis noted in a lengthy written statement that tenant leases “clearly outline that all residents shall be charged for damages caused by the resident” — which the family did not dispute; in fact, they provided a copy of their lease to Task & Purpose — and “residents shall be charged for all damage to the premises as a result of failure to report a problem in a timely manner,” Dennis said. “In addition, residents shall be charged for repair of drain blockages or stoppages caused by resident misuse.”

The statement went on to explain that families must attend a briefing regarding base housing before they move in and officials strongly recommend the use of comprehensive renters insurance for families living on or off base, since tenants “can be held liable for any damages sustained to their residence dependent on the coverage provided by their existing insurance policy,” said Dennis, with potential costs ranging from a “couple hundred dollars to tens-of-thousands.”

Dennis added that a comprehensive information campaign was recently launched to “educate and encourage” tenants on having a robust insurance policy. A public affairs story published on June 2, for example, suggested that renters insurance would have helped in a hypothetical case of a microwave catching on fire. But as the Salchows maintain, renters insurance didn’t help in the real-life case of their washing machine malfunctioning while they were away from home.

“This was not misuse on our behalf,” Richard said. “The water valve broke, and we were not using the washing machine inappropriately. We did have a full renters insurance policy, with liability coverage,” he added, saying that Dennis’ statement that service members should “purchase comprehensive renters insurance” was misleading.

But in the middle of moving across the country — the family is heading to a new base on the east coast — and trying to check out of their current home in time, the Salchows have decided to just pay it and get it over with, though they worry that other Marines could face similar bills with little means to pay.

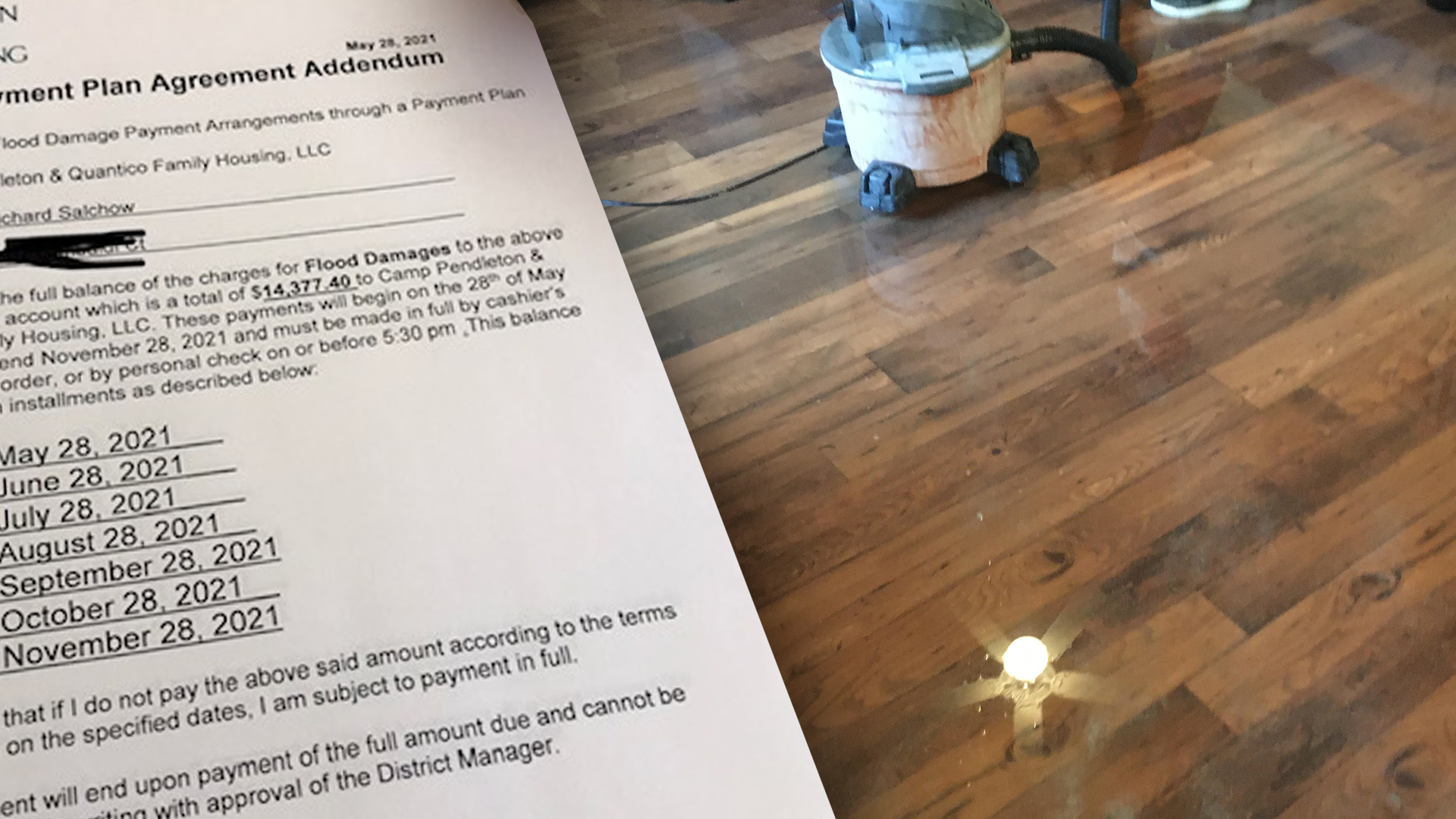

“I’d love to keep fighting this but at the same time we’re in the process of closing on a house and I really want to just get this over with and move on,” said Colleen, who said their biggest fear was Richard’s security clearance being affected in the dispute. They agreed to a payment plan in late May with an upfront $3,594 payment and subsequent payments of nearly $1,800 every month until November. The agreement noted the charges were due to “flood damages.”

Even so, they can’t help thinking back to their washing machine from before the flood — the washing machine that worked perfectly until they put in a load, hit start, and it didn’t — because the house they moved into on base didn’t come with one. If Lincoln had supplied the washer and dryer, the company would have been responsible for the property damage. But because the washer was the property of the Salchows, and since the home existed in an insurance grey area — where it was located on base, but not considered government housing — that meant that it was their problem. As was the stress it brought on top of daily military life: months of back-and-forth with base housing officials and the chain of command; phone calls and live chats with insurance agents; and yet another complaint being shared widely on social media about privatized military housing.

The military community has no shortage of base housing horror stories. As a special report from Reuters found in 2018, thousands of military families in privatized military housing had been subjected to “serious health and safety hazards” that included lead poisoning risk, pest infestations, and rampant mold, prompting the Defense Department to introduce the Tenant Bill of Rights.

Despite base officials’ urging the purchase of renters insurance — which, to be clear, has many benefits and does indeed cover an extensive range of issues — Richard and Colleen believe their experience has exposed a “gap” that military leaders should be aware of and other service members need to know about.

“It is imperative that military families have an emergency fund that they can use in such an event, until a policy is offered,” Richard said.