Soldiers in Alaska will be saying goodbye to Arctic-challenged Stryker vehicles, in a move that service leaders hope will improve their day-to-day lives — and by extension, the lives of their families.

The Army announced this week that the 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, would be redesignated as the 1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 11th Airborne Division. The change is part of the Army’s reactivation of the division, which unites soldiers from two brigades previously with the 25th Infantry Division based in Hawaii, and U.S. Army Alaska.

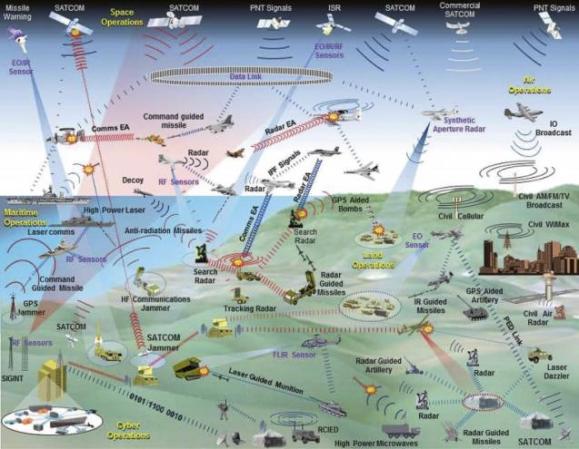

The division, which has been deactivated since 1965, will be at the center of the Army’s arctic strategy, looking ahead to a possible conflict with Russia and China. The Strykers are one change coming to soldiers in Alaska, which according to Military.com, who first reported the news, were “no good in the frigid and snowy Arctic conditions.”

Indeed, during a roundtable with Sgt. Maj. of the Army Michael Grinston on Monday, division Command Sgt. Maj. Vern Daley said the vehicles are “not well-suited for the Arctic environment, they’re very difficult to maintain, they haven’t been very mobile in that environment. And the ability for 1-11 now to be able to focus on their light infantry tasks and not have to worry about the maintenance and the headache that they’ve had.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

It’s unclear where the Strykers will be going, though Army Secretary Christine Wormuth recently said if they aren’t used elsewhere in the force they’ll be scrapped for parts. But leaders hope that by getting rid of the Strykers, soldiers and their families — will be happier, which will create a more positive climate and culture. And making a positive climate in Alaska has been a top priority for the Army, as units in the region have been facing rising suicide rates.

During the roundtable on Monday, Grinston recalled “casually” mentioning the idea of getting rid of the Strykers in Alaska several months ago while he was at Fort Knox, Kentucky. “I got a round of applause,” he said.

When a soldier is spending all their time working on vehicles that have no chance of success in that environment anyway, that stress bleeds into their home and family life, Grinston said. It creates a slippery slope which could lead to their spouse or loved ones leaving because they’re “never home anyway,” which in turn could lead to the soldier drinking more or spending more time alone.

“I can really see this as getting rid of those Strykers is really help for resiliency,” Grinston said.

Alaska has been a primary point of concern for Army leaders over the years, as the number of suicides has been on the rise. In 2021, the number of soldiers who died by suicide was double that of the previous year, setting off alarm bells in the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill. In April this year, lawmakers urged Army Secretary Christine Wormuth in a letter to do more to address the rise in suicide in Alaska.

Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-Alaska) wrote that his state has “horrifically high rates of military suicide.” Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) agreed, calling out the “troubling” trend of suicides in Alaska compared to other military communities.

“I’ve heard firsthand from so many servicemen and women in Alaska about the challenges they face — from physical and psychological trauma, isolation, to seasonal depression,” Murkowski said. “We need to do everything in our power to turn this tide and be there for our service members — to get them the proper help they need so suicide is never the answer.”

The Army has poured resources into Alaska to provide more access to mental health care and even made small changes like providing vitamin D tablets and keeping the gyms open longer. But service leaders also hope that the activation of the 11th Airborne Division in Alaska contributes to positive change by giving the roughly 12,000 soldiers an identity to hold onto.

“Arctic warfighting is not just what they do, it’s really who they are,” Army Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville told reporters on Monday. “And that’s the identity these great soldiers are going to have in the 11th Airborne Division.”

But leaders also see the change with the Stryker brigade as a positive step in making life easier for soldiers. During a trip to Alaska this spring, Military.com reported that a training exercise was delayed because the Strykers had broken down on the way to the training site. One mechanic told Military.com that the vehicles were “meant for the desert,” but out in Alaska, they “just freeze.” And it’s not just the challenges soldiers were having with them, but the money the Army was spending trying to maintain them.

Daley mentioned on Monday the “incredible amount of money the Army has had to pour in” to facilities and heating shelters, all in an attempt to get the Strykers operational. And Grinston said that if a soldier is spending “an extremely long amount of time at work trying to fix a vehicle that does not operate in the cold,” it will frustrate their family who is seeing them less. And when that soldier returns to work and goes out into the field, only to have the vehicle they’ve spent so much time trying to maintain break down again, that frustration will only worsen.

“Overwhelmingly,” Daley said, “there is a lot of relief in having the Strykers move out.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Someone apparently leaked classified Chinese tank schematics to win an online argument

- Flip-flop-wearing Air Force commandos saved 2 lives on the way back from training

- How Ukraine is using artillery to stop Russian forces in their tracks

- The Navy might have a garage sale for the Littoral Combat Ships they just built but don’t want

- Ukrainian fighter calls US soldier for help fixing Javelin missile launcher

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.