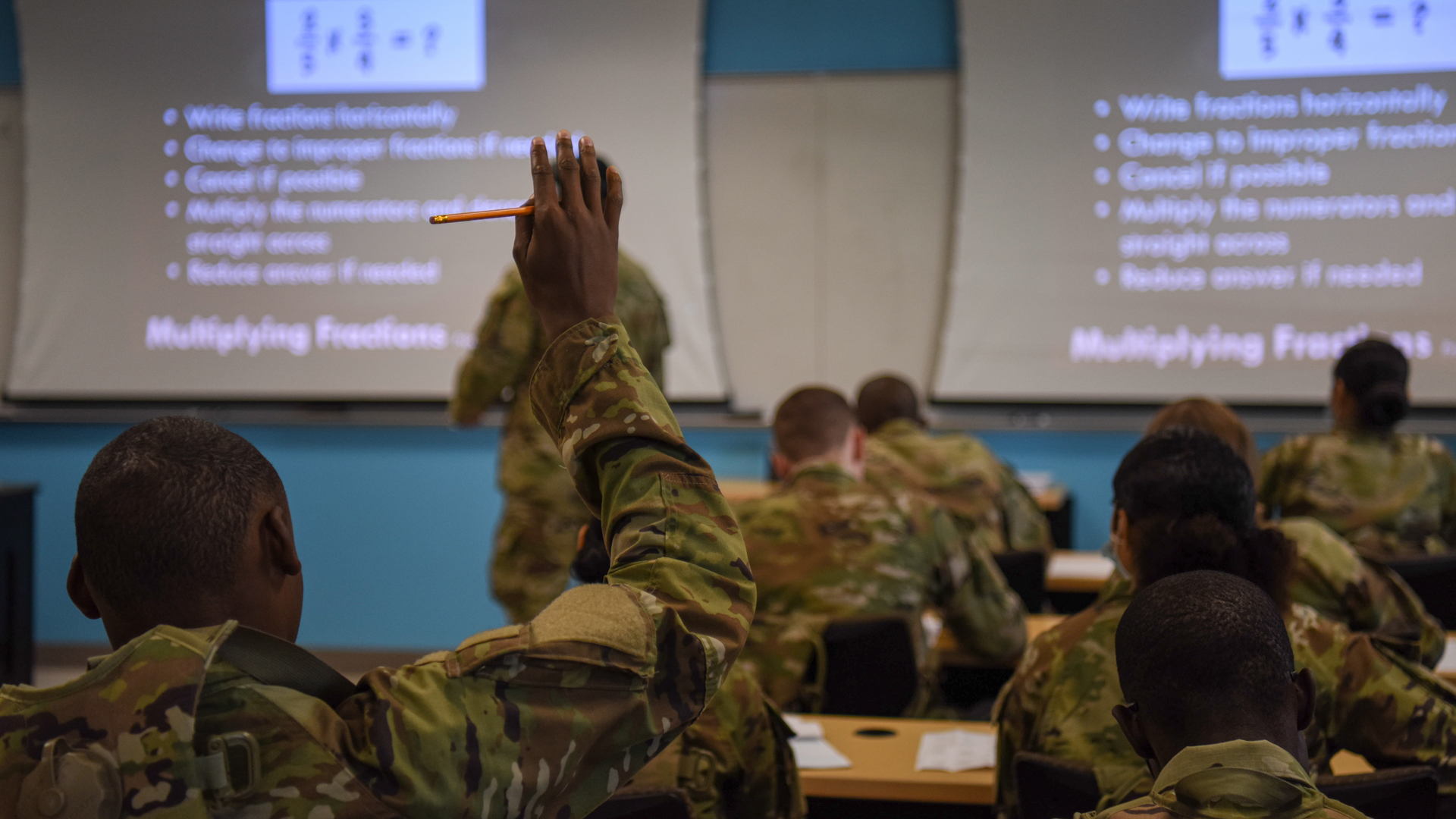

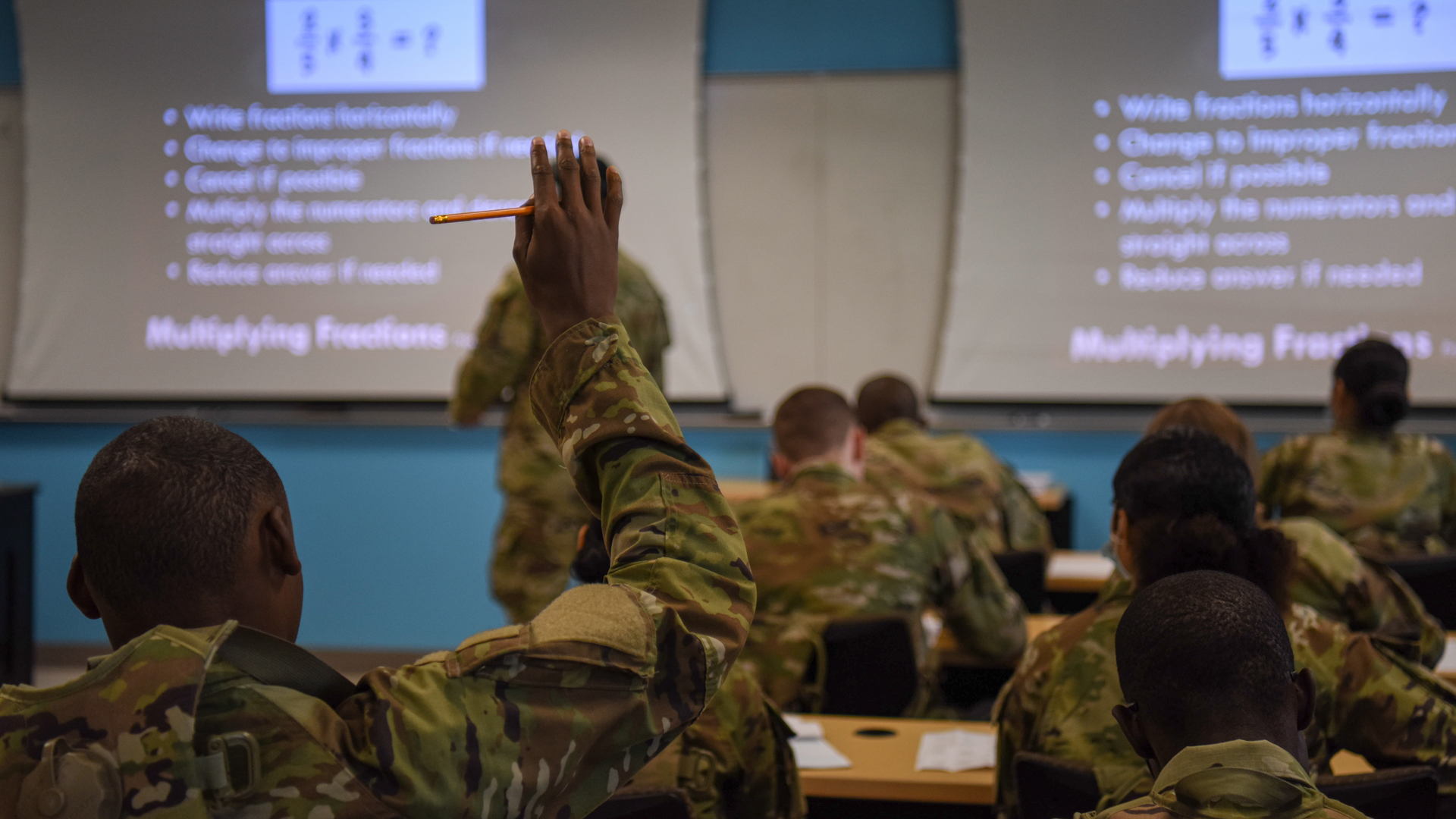

Drill sergeants at the Future Soldier Prep Course are not your average drill sergeants.

The instructors at the course, a new initiative launched this summer to help get more potential soldiers qualified to serve, are meant to “inspire” hopeful soldiers more than strike the fear of God into them. There’s no “physical corrective action” for simply looking too happy to be there, or any other mundane issue drill sergeants might find problems with.

“No physical corrective action, is what they call it,” Capt. Nancy Butler, a company commander in the 1st Battalion, 61st Infantry Regiment told Task & Purpose last week. “It just doesn’t have a place in the classroom, it’s actually not very conducive for the learning environment.”

Needless to say, the Future Soldier Prep Course is a new way of doing things. Introduced in July, the course is meant to help get aspiring trainees within Army standards so they can ship off to basic, whether that requires working on their testing scores for the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), or doing physical training to be within the weight requirement. The pilot program for the course was started at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and while it’s still in the early stages, leaders said last week that all signs were pointing to success.

“We have started the Future Soldier Prep Course, as I said in my speech the early results of that look pretty promising,” Army Secretary Christine Wormuth told reporters at the Association of the U.S. Army’s annual conference last week. “And depending on how that plays out in the next month or two I think we will look at expanding that to some additional training sites, which would obviously help us.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Indeed, the Army needs all the help it can get. The service missed its recruiting goal by 15,000 soldiers after experiencing the worst recruiting crisis in decades. Army leaders have pointed to a decline in interest to serve among young Americans as a reason for the gap in recruitment, as well as the failure to meet Army requirements that the prep course is seeking to fix.

The roughly 1,070 people who have come into the course since its inception — who are called “students” rather than trainee — can go to one of the two tracks, focusing on either their academic performance or physical fitness, but never both simultaneously. The students enlist under 09M delayed training contracts and have 90 days to get within the standards for whichever track they’re on. If they don’t meet the requirements they need to meet within those 90 days, the Army separates them under a Chapter 11, which essentially means they can come back and try again in six months.

As of Oct. 1, 706 students have gone into the academic course since it started in August, with 581 finishing and heading to basic training. On the physical fitness side, 366 students have entered the course, with 292 having graduated thus far.

The drill sergeant cadre, who are working alongside civilian instructors, take on a more “inspirational role,” Butler told Task & Purpose at AUSA last week — a bit different than what soldiers might typically expect from a drill sergeant. Instead, they are focused on building students’ “mental resiliency,” and using their experience in the Army as inspiration for students in how to overcome obstacles.

“It’s not the hard standard disciplinarian and instructor that they’re used to as a drill sergeant,” said Lt. Col. Dan Hayes, commander of the future soldier prep course. “One that’s connecting to their students and helping determine what is the limiting factor in them achieving their true potential. And what we learned from a disciplinary side, is the vast majority of those who perhaps are not acting the best typically are the ones struggling the most in the classroom. And once you connect to them and figure out how or where they’re falling short in education, now all of a sudden they’re performing.”

It’s the same for the students on the physical training side of the house, who are focusing on learning life-long tools to help them stay healthy as much as they are doing the physical training.

Capt. Remedios Timo-Dondoyano, the fitness training company commander at the course, said drill sergeants take on more of a coaching mentality than the typical drill sergeant approach, because “some cues don’t work for everybody.” Instructors want students to learn how to track their workouts and their nutrition, ensure they’re eating enough of the right foods, and learn individualized exercise plans for their body type. Timo-Dondoyano said most students end up leaving the course for basic training before that 90-day mark.

On the academic side, students start the day with PT — it is still the Army, after all — and then have a 9-5 day of instruction on topics like math and reading comprehension from a civilian instructor. Students will practice testing to improve their scores, with instruction available in both English and Spanish, and take the ASVAB every three weeks. If they meet the score, they’ll be moved on to basic training and continue on like any other trainee. If not, they’ll continue through another three-week period of teaching and try again.

But no matter which track a student is on, they’re experiencing the Army’s H2F approach. The intent of H2F is to build healthier, more durable soldiers by focusing on nutrition, sleep, and spiritual and mental wellness in addition to physical training.

The Army has been investing in bringing in dieticians, nutritionists, and physical therapists to ensure that soldiers are training the right way. Butler said that while basic trainees might be getting six hours of sleep or less, that’s “not great for resiliency or for cognitive function.” And when it comes to daily PT, she added that the intent is not to run them “into the ground,” but to focus on “movement patterns, introducing muscular strength and endurance, so that when they get to basic training we’re not giving broken goods back to the Army.”

“We want to help them write a successful Army story, not break them off right at the start,” she added.

All in all, how the prep course is run is somewhat similar to how the Army is shifting its basic training to be. As Military.com reported on Tuesday, the service has already started pulling back on the stereotypically loud and belligerent drill sergeant and sought to replace that mentality with that of “strict football coaches.” Instead, training is focusing on making fitness and marksmanship requirements more demanding, Military.com reported.

Depending on the prep course’s success, it could further influence changes to basic training. And ultimately, leaders are confident that not only will the students going through the course be successful as soldiers, but possibly more successful than soldiers who are joining up without having gone through the course. Maj. Gen. John Kline, commander of the U.S. Army Center for Initial Military Training, told Task & Purpose that’s the “big thing that we don’t know yet,” is how a student who graduates from the course “is going to compete against an individual that’s right off the street.”

“I would argue, my assumption is that they’re actually going to do better,” Kline said. “Because they’ve been in this culture for a little while, they’re on a diet, they’re on the right sleep schedule, they’re getting all the components of H2F, they’re learning our values, they are doing PT even if they are on the academic side. Soldierization is taking place. So I’m excited to find out once they go through basic training whether or not their attrition rate is better than the others.”

And while some critics may think this means the Army is going soft to help people get into uniform, those running the course couldn’t disagree more. Timo-Dondoyano, the fitness training company commander, said the course is making the Army better because it’s not only giving people who are really passionate about serving an opportunity to do so, but it’s ensuring they come in healthy and ready to go.

“We want those educated, young new soldiers that enter their first duty station to be empowered and enabled,” she said, “so that they are going to be as healthy as possible to start their career.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Orca submarine is yet another case of the Navy spending money like a drunken sailor

- What if the sailor charged in the Bonhomme Richard fire was actually a minor hero?

- Woke Army or Woe Army: What really happened in the social media controversy rocking the force?

- Watch a Ukrainian soldier take out a Russian cruise missile with a MANPADS

- The end of the brown beret: Air Force special ops squadron shuts down after 28 years advising allied aviators

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.