Matt Stark* came home from war with an honorable discharge, a traumatic brain injury (TBI), and a bad case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He was a tough guy — muscular, six-foot-two, 220 pounds — a decorated Marine whose life had fallen apart after he left the Corps. He was 32.

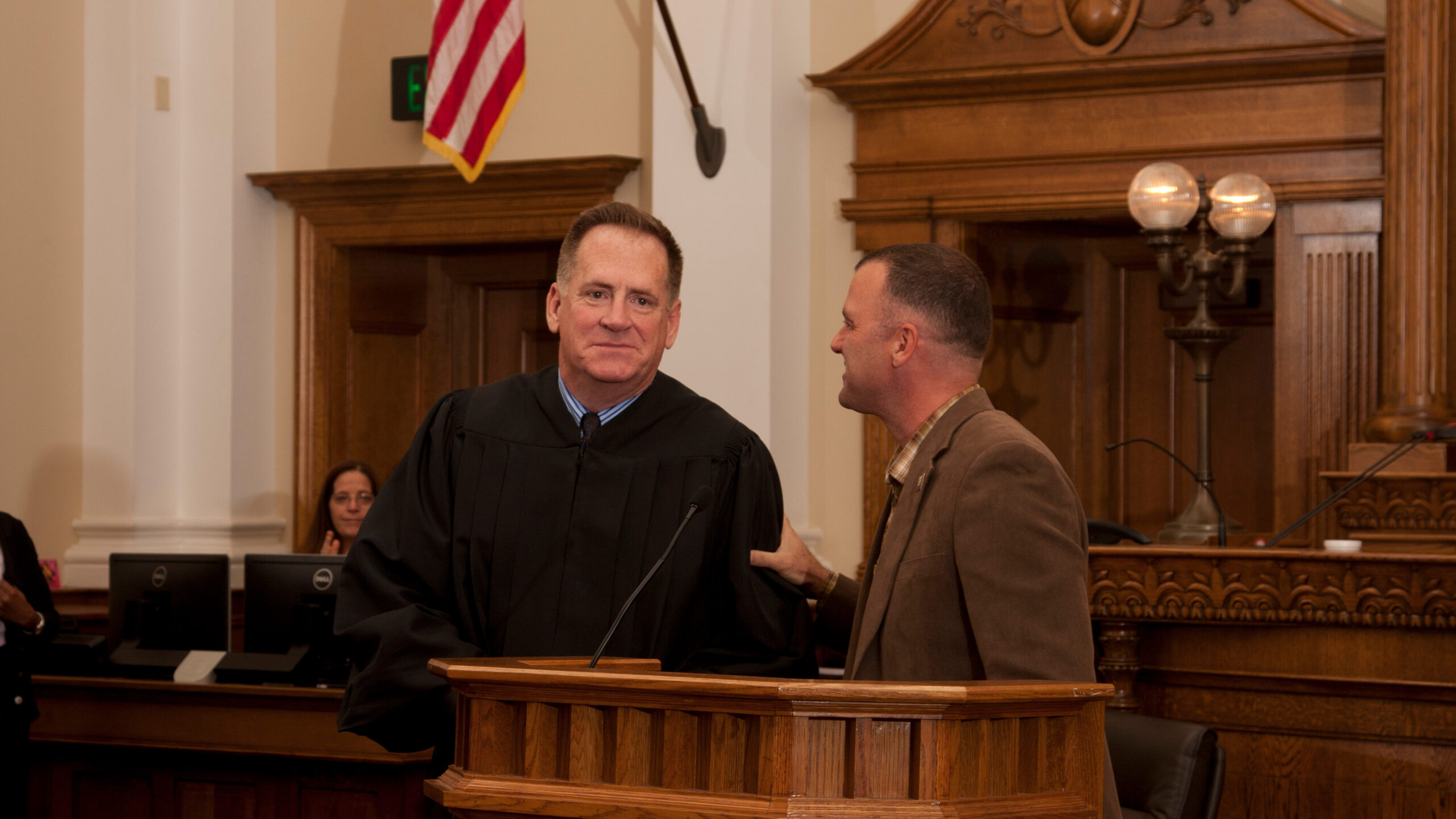

Like many who stand before me in the courtroom, Matt had turned to methamphetamine. I was the judge presiding over his case in the Riverside County Veterans Court. He had been in our program for 11 months and had, once again, tested positive for meth. (*Editor’s note: Matt Stark is a pseudonym).

“Matt,” I said. “I’m tired of sanctioning you.” Sanctions are corrections ranging from a lecture to jail time. His posture was that of a 6-year-old boy in serious trouble. “I don’t know how to help you,” I said. “What do I need to do?”

He moved his lips but made no sound, then started to cry. “I don’t have a mission anymore.”

I have worked with hundreds of combat veterans who feel the same way. Their lives once had great purpose – they led men into battle and had tight bonds with the warriors who watched their six, then returned home to a world they no longer understood.

Behaviors that once made sense — aggression, hypervigilance — now get them into trouble. Flashbacks become commonplace. The legal system does not trust them with their children. Like Matt, these veterans turn to alcohol and illegal drugs to alleviate symptoms. Then everything goes to hell and they find themselves in my courtroom.

I had a bad feeling that day looking at Matt. On the Myers-Briggs personality test, I rate high in Intuition. I trust that inner voice. Gut feelings often guide my decisions. That’s not something I advertise. Who wants to believe their judge makes rulings based on “vibes?” But, seeing how broken and defeated Matt was, I feared he would kill himself.

“Take a seat, Matt,” I said. “I want to talk to your team.”

Our treatment team has representatives from the Veterans Administration and the District Attorney, Public Defender, Mental Health and Probation. I said I was worried Matt was suicidal and suggested putting him in jail for a violation of probation. Sanctions are limited to three days in jail. A probation violation would have allowed me to keep Matt locked up for weeks, giving us time to find another drug-treatment program. Jail would be humiliating and bleak, but he would not be able to hurt himself.

But gut feelings are not transferable. Everyone else thought jail was too severe, so I backed off and sanctioned Matt with community service at a horse rescue ranch. I thought it might help.

“Matt,” I said, “we’re going to have you work with some horses. And the VA will find another residential program. That will take a few weeks. We’re in this together, Marine.”

Matt never did work with those horses. Twelve days later, he was found dead on a bed in a cheap motel. Chronic methamphetamine abuse had killed him.

Veterans Court is based on the drug court model. To enter our 18-month program, the veteran must plead guilty and be placed on probation. Veterans are drug-tested three times each week and must come to court every Friday. With close judicial supervision, I can address problems before they get out of hand. Positive behavior is rewarded. This process is vastly different than it is in most other courts, where it can take months to address a violation. Relapses are expected as part of the recovery process. Some veterans relapse a dozen times before achieving long-lasting sobriety. But I expect more from veterans as they progress. An early relapse is treated with leniency. In later phases, veterans are expected to know their triggers and have developed coping mechanisms. Matt had been in our program for almost a year. He recently had returned from Metcalf Recovery Ranch, a 60-day residential drug-treatment program in Blythe, California. Veteran addicts who surrender to the program generally show great progress after 11 months. Not so for Matt.

+++

I had been a judge for two years when I led a committee to set up our veterans court. I chaired meetings with representatives from county agencies, veterans’ groups and the Veterans Administration. Our first session was held on Jan. 5, 2012.

I thought I was perfect for the job. As a retired Army colonel and Iraq War veteran with 28 years in uniform, I understood the challenges facing our veterans. Drawing on leadership skills gained from company and battalion commands, I saw my role as a judge expanded. Presiding over the court would be a sacred trust between the veterans, the public and me. These veterans would know I was there to help them regain their honor. We would give back to society together. I would lead from the front.

My wife Kim and I worked side by side on community service projects with veterans convicted of felonies. Kim is tough and wise. We met in 2013 and married in 2015. As a single mom, she raised six children adopted from the foster system.

Together, we worked with veterans cleaning up trash in local parks. We volunteered at animal shelters. We found homeless veterans and worked to get them housing.

I started the Veterans Court Ruck Challenge, a fundraiser to help a charity provide housing for veterans. Four-person teams walked for 10 kilometers, each member carrying a 50-pound rucksack. Veterans from the court had to carry a ruck or work to support the event. The Competition would inspire veterans on their paths to healing.

I was at least 25 years older than the other competitors, and my team – dubbed Born to be Wild – came in last. It didn’t matter. I competed and carried the weight, took the pain.

Matt was always at these events. He always looked sad. I tried to make him feel better. “You’ll get there,” I’d say.

Once, after a park cleanup, Matt stood up as Kim approached him, and he gave her his chair. This closeness with probationers is unusual for a judge. Fellow jurists approached me, questioning my prudence. Judges generally steer clear of contact with people who appear before them. One reason is fear of violating a judicial ethical rule: avoid the appearance of impropriety.

Mainly, I think most are afraid of getting attacked by a felon. I think that attitude is cowardly. A judge should set an example. I was a retired colonel who had been shot at and bombed. I was bringing a warrior’s mindset to the fight against mental illness. I would not let fear keep me off the field. Nothing would stand in the way of helping my brothers and sisters to heal.

+++

On April 10, 2015, Matt called his mom, Deborah, asking for a ride to a drug rehabilitation program. However, when she arrived, he demanded she take him to buy beer and give him $160 for car repairs. Agitated, screaming and high on meth, Matt grabbed Deborah by her hair and forced her to drive to an ATM machine.

After returning to her home, Matt tried to take his mom’s car keys. When she resisted, he smashed her face into the driver’s-side window, then dragged her to her front door. She fell, hitting her head, then screamed. Matt grabbed her keys and drove away. Deborah called 911.

The police found Matt in Deborah’s car, parked in front of his home. He was arrested for kidnapping in the commission of carjacking, which carries a life sentence. The district attorney added charges of carjacking, robbery and felony assault. His bail was set at $1 million. Matt was arraigned in Indio on April 14, 2015.

Eight days later, I opted to keep Matt’s bail at $1 million and referred him for a psychological/social history evaluation and for assessments by the VA and probation. I learned the following from those reports and from speaking with two Marines who served with him:

Matt was born on Feb. 28, 1984. He entered active duty with the Marine Corps on March 17, 2003, when he was 19. His parents were divorced, and Deborah, his mother, had remarried.

Matt served two tours in Iraq. His service record included decorations for courage under fire. Fellow Marines described him as a selfless leader. Matt and I were both in Iraq in 2004 but serving at different echelons. I worked at the national level. Matt was a grunt, fighting in Ramadi and Fallujah.

After four years, following a diagnosis of PTSD and traumatic brain injury, Matt was discharged honorably. The Veterans Administration awarded him 100% disability.

For TBI, Matt was prescribed oxycontin. President Trump’s 2017 declaration that opioids were causing a “public health emergency” affirmed something the VA had known for at least six years: opioids were killing our veterans. According to a 2011 study by the VA healthcare system, veterans were twice as likely to die from an opioid overdose than non-veterans.

Matt married Melody in 2009. Their daughter Samantha was born in 2010. A second child, Emily, was born in 2011. Eventually the VA stopped prescribing opioids for Matt. But by then, he was an addict and had turned to street drugs, primarily meth.

In 2012, Matt and his family relocated to Utah. In 2013 and 2014, he attended three residential drug-treatment programs in California. His relationship with Melody was collapsing. In the Fall of 2014, Melody filed for divorce and obtained a restraining order keeping Matt away from herself, his daughters and their home in Utah. Matt then moved to Indio, California. When he appeared in my courtroom, he had not spoken to either of his daughters for seven months.

Even though Matt had no criminal record, I knew before accepting him that the path ahead would be tough. A risk assessment had defined Matt as “high risk, high need,” meaning both his treatment needs and chances of failing were extreme. Only an intensive program had a chance of success.

Melody wanted nothing to do with him at this point. I understood her decision. His behavior was out of control.

Deborah also was uncooperative in the assessment process. Matt described her as an abusive alcoholic. He reported that, upon his return home after his discharge, Deborah’s husband called him a “baby killer” and did not want him around.

Some men beat women and their violence has nothing to do with their service. They are not welcome in our program. But I believed Matt was a decent man whose violence was related to his service. For that reason, I accepted him.

Matt pleaded guilty on May 8, 2015, to carjacking, felony assault and robbery. The prosecution agreed to dismiss the most serious charge: kidnapping. Matt’s convictions otherwise would have resulted in a lengthy state prison sentence. However, the prosecutor agreed to probation because of Matt’s service and clean record.

I placed Matt on probation and said the same words I have told hundreds of veterans: “Mr. Stark, when I look at you, I don’t see a criminal. I see that young guy on the automatic weapon protecting my ass as I traveled in Iraq. I see a hero.”

I continued: “We have a tough fight ahead. Our enemy is more cunning than any insurgent you’ve faced. It wants to destroy you. It will make you believe lies. But we fight as a team.

“From you? I need 100% honesty. I need you to open up, to volunteer the unvarnished truth about your pain. You need to tell your story in treatment. For our enemy has a weakness. It operates in darkness. It scurries like a cockroach when we shine the sunlight of truth on it. We will prevail.

“Can you do that for me?”

“Yes,” Matt said.

I was describing Cognitive Processing Therapy, a primary treatment for PTSD. During CPT, veterans write about their trauma. Then they read what they wrote and share the darkness with others. Bringing trauma out into the open induces healing. It’s a tough process. The main reason these veterans used drugs was to avoid pain. CPT asks them to relive their trauma.

+++

Working with addicts and alcoholics is frustrating. One week, I would congratulate a veteran. The next, he would miss drug tests and his court appearance. A judge should never take relapses by an addict personally. But because I cared so much, I often did. I’d vent to Kim, “I feel like I’m back in Baghdad. It’s three steps forward, two steps back. Or vice versa.”

But I never told her much about my time overseas. I deployed to Iraq from 2003 through late 2004. I was the First Cavalry Division’s advisor to the Baghdad Provincial Council. We were developing democracy. I was doing God’s work, or at least Thomas Jefferson’s.

I loved the Iraqis with whom I worked. Once I was friends with several council members. We drank tea, traded smokes and shared family photographs. They were mesmerized by my 7-year-old daughter Erica’s long auburn hair. None of their wives or daughters had hair that color.

“So beautiful,” they said, passing her photograph around. Their reactions were naïve, refreshing. They had a simple faith in me. But they were always getting killed. One day, a seat at a meeting was vacant and I learned a friend had been murdered, his body butchered, his limbs strung up at a traffic light. It was a warning: “Do not help the Americans!”

I was the American he’d helped. Insurgents hung another friend off the side of a building. Four council members were ambushed. After a while, I quit making friends with Iraqis.

Once, a councilwoman named Ilham was kidnapped. Her family couldn’t pay the ransom, so she was buried alive. Ilham was beautiful, tall, and happy. She wore bright pastel kaftan dresses and matching scarves covering her hair and neck. Once, after she passed by me in the Baghdad City Hall, I said to another officer, “That lady can rock a hijab.”

The day before she disappeared, Ilham walked up, smiling. She wanted money for a women’s empowerment center for her village. She picked the wrong day to ask.

Earlier that day, I had been standing at a window when I heard what sounded like a freight train bearing down, followed by a massive thump. A rocket had struck 20 feet outside the window of my office. The warhead did not detonate. If it had, I would have come home in a box.

“Jesus Christ, Ilham.” I’d had no sleep in 30 hours and had just nearly been killed. My voice raised, I told her how stupid it would be to build a “women’s empowerment center” in a village that lacked running water and a sewage system, yet was filled with insurgents who would love to blow it up.

Her jaw dropped. Her mouth stayed open. She teared up, spun around and walked away. I never saw her again. For years, I kept Ilham’s photo in my wallet.

+++

PTSD is a psychiatric disorder that occurs in people who have witnessed or experienced trauma. Nightmares and flashbacks are classic symptoms. People with PTSD learn to avoid stimuli related to trauma. PTSD destroys marriages and families. It often leads to the incarceration or death of those it afflicts.

In flashbacks, the veteran relives a terrifying incident — even feeling sensations experienced during the trauma. Matt had seen Marines killed and continued to experience their deaths. “I can’t take the nightmares,” he told therapists.

Imagine smelling exhaust — one of his triggers — and finding yourself back in Ramadi watching your best friend get blown away? Meth and alcohol numb the symptoms. The veteran feels better. But drugs also change the wiring of an addict’s brain to the extent that feeling good, or even OK, is impossible unless they use.

Matt’s therapists reported that he didn’t want to talk about his trauma. “You need to open up, shine light on what hurts,” I said, saying things I thought would help.

Everybody liked Matt. Big, humble and always struggling, he would reach a month of sobriety only to relapse. Once he made it almost two months.

I sanctioned him with reprimands, community service, and assigned essays on what triggered his relapses. His therapists reported he was trying. He wanted to get better.

Judges sit higher. We see more. The hopelessness in Matt’s eyes the day he broke down scared me. I thought he should be confined for his own safety. I was the one society trusted to make the call. I should have locked him up.

+++

A week after Matt died, we held his service at the Loma Linda VA Chapel. Deborah blamed us for Matt’s death and refused to attend. We expected such a response from her. She had never come to court. Forty veterans attended. Luis Garcia, Matt’s friend, performed a song written to honor him.

I said a few words:. “Matt was a hero. He loved his daughters and fellow veterans. It is our duty to continue healing. In doing so, we honor him.”

On the altar was a plaque with two photographs. In one, Matt is on his motorcycle. In the second, he is holding his daughters. He looks happy.

+++

In June 2016, I spoke at VetCon 2016, the annual veterans court convention. I was on a panel with two judges and Jack O’Connell, the chief mentor of a New York veterans court. My wife was among the more than 400 people in the audience.

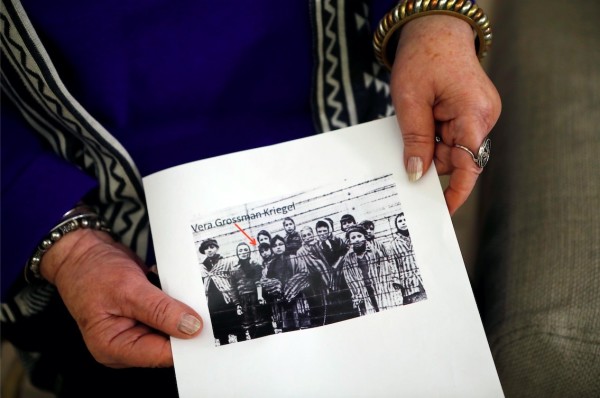

Each judge had 20 minutes to speak. I had one slide, the photograph of Matt with his daughters. The caption read, “WHY WE ARE HERE.”

My plan was to capture the audience’s attention with Matt’s story. “Always start strong,” I advised young lawyers struggling to craft a powerful opening statement. I began, then looked at Matt’s image. A wave started in my gut and rose to my chest. Moving quickly, it lodged in my throat. I couldn’t talk. I started crying.

Fifteen seconds later, still silent and watching an audience shifting uncomfortably, I felt Jack O’Connell squeeze my arm. It helped and I continued to speak. “Sorry,” I said.

Afterward, Kim and I went to lunch. “Why did you get so sad up there?” she asked. “I’ve never seen you cry.”

“I didn’t cry,” I said. She squinted.

“Come on,” she said. “What’s going on? You never talk about these things. I know you spent a year in Iraq, but not much else. You tell me funny stories about court. That’s it. I see things bother you.”

“I’m not a woman,” I said.

She rolled her eyes. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“I’m not unloading on you every time something bothers me. That’s what you guys do. I have to set an example.”

“I’m your wife. Sometimes you sit up at night in bed and yell out. Then you put your feet on the floor and stay that way for 10, 20 minutes. What are you dreaming about?”

“I don’t know.”

But it was always the same. I am standing by a window, watching a rocket moving in slow motion. The tip of the warhead grows close. It’s so loud. I try to drop but I am frozen. The roar is deafening; then, the warhead hits outside and detonates. I feel searing pain as the window shatters. Glass shreds my body. I wake up.

“It scares me,” she said. “Whatever you’re dreaming scares you. Maybe you should go to a doctor at the VA.”

“I don’t need a fuckin’ shrink. I’m fine.”

Kim is an easy read. She was worried. I knew I should say more.

“I’m sorry for Matt,” I said. “He was 32. I’ve seen pictures of him with his girls.”

Kim nodded. “Don’t you always say, working with addicts, that sometimes you’ll lose one?”

“That shit’s easy to say when you haven’t lost one. In 28 years, I never lost a soldier under my command.”

“Is that why you got upset?”

Those tears came out of nowhere. I did not entirely understand my emotions.

“I should have locked him up,” I said. “If I’d locked him up, then sent him to a residential program, he’d be alive.”

She shook her head. “You didn’t give him the drugs. He did this to himself. You know that, don’t you? Are you listening to me?”

She raised her voice. “Are you listening?”

“Yes.”

“Haven’t I heard you say that anybody who thinks he can control another man’s addiction is dreaming?” she asked. “Egotistical?”

I did not answer.

“Why do you think you’re somehow better than everybody else?” Kim asked. “I know you did your best. You need to put this one down.”

+++

For the first four years, I loved presiding over the court. We had a low recidivism rate. Statistically, 70% of inmates released from state prison commit a crime within three years. Among our graduates, it was 12%.

But after Matt died, I was burnt out. “We’re doing more to help you than you’re doing for yourself,” I told veterans who came before me. But they were still only humans struggling with mental illness and addiction.

I got weary of relapses. I saw failure in every mistake. I got sick of listening to stories about wasting kids and seeing buddies die. After five years in Veterans Court, I asked to leave.

In January 2017, I was assigned to a calendar position, presiding over cases before trial. Every day, I called between 70 to 200 cases. There was no opportunity for personal interaction with defendants.

I did not have that same sense of purpose I had found in working with veterans, so I asked to return to Veterans Court and, in April 2019, I was reassigned there.

+++

I learned a lot from veterans like Matt and wanted to write something to help others. I sent Deborah an email on January 28, 2020:

I was Matt’s judge in Veterans Court. I cared for your son. I have always been so sorry we couldn’t save him. I would like to honor him by writing something to help other veterans. Can we talk sometime?

Within minutes, I received her response:

I don’t know what scam you’re playing, but how dare you to try and play on my pain and emotions. VA and VA courts did NOTHING to help my son!

I did not reply.

On February 5, I mailed a letter to Matt’s wife, Melody, expressing my condolences and asking if I could talk with her. She did not respond. But I did receive three unsolicited emails from Deborah on February 10.

Leave our family alone! If you want to contact someone, contact Mr. Gordon, his probation officer that failed him like you and VA did. You can all share your failure.

And as an FYI, my other son committed suicide, blew his brains out in 2008 at Camp Pendleton, so they say. They put him on some depression medication and never followed up with him. Thank you VA for taking both of my sons!

Deborah lost her younger son, Samuel, on May 17, 2008. A 19-year-old lance corporal in the Marine Corps, he shot himself in the head with his M-16. Samuel was taking Prozac and prescription diet pills and had a history of depression, methamphetamine abuse and a previous suicide attempt. A young woman he loved had ended their relationship days before he took his life.

I was mad and typed a response expressing what I thought of a mother who wouldn’t support our efforts to help her son, then blamed us for his death. Just as I was ready to hit send, I received an email from Luis Garcia, the Navy corpsman (medic) who sang at Matt’s service. I had written to him a week before.

Luis’s life had been a mess. Much like Matt, he had struggled in our program. Then something miraculous happened at Metcalf Ranch. He began to recover. He graduated from Veterans Court. Two years later, I dismissed his convictions.

Today, Luis is a supervisor at the VA Hospital in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He works helping veterans with PTSD and addiction. He is married, with a 2-year-old daughter. This is what he wrote to me:

Your Honor,

I was close to Matt, but unfortunately, as quickly as I got close to him, he passed. Let me tell you what I do know about Matt. I first met Matt in an AA meeting at the Veterans Hospital in Loma Linda. What drew me to Matt was his desire to get clean, a passion we both fantasized about. Matt liked you, believed in you and was excited to be in the Program. He believed the program was the only one qualified to help him with his addiction. He was happier than on the streets because he saw hope in the Veterans Court Program. I believe Matt would have died from drug abuse without Veterans Court, his drug abuse was that bad. At least with Veterans Court he died with hope in his heart.

All these things we shared, wanting to get clean and harmful drug addictions, are what drew us together. The night Matt died, he called. I wish he would have called before he relapsed. Things would be different today. He wanted me to pick him up. Because he was using, I told him no. I regret that decision to this day. I wish at the time I was stronger, but I wasn’t.

Like you, I took his death hard, so much that after four months clean, I used. That was the last time I ever used. I promised myself his death would not be in vain. You threw the book at me for that. Who could blame you, you just lost Matt. You sent me to Metcalf Ranch, where I slept in Matt’s bed and spoke his story. Matt’s tragedy sparked something inside of me to get better that still burns inside of me. Matt was a leader. He had integrity and honor. He was committed and loyal. He loved his daughters, hated his ex-wife and mother for obvious reasons. Matt was a really good guy. Your instincts about him were dead on!

Do not be discouraged after speaking with his mother. His mother was abusive towards him growing up. She was also a considerable influence on his addiction. She is a suffering addict herself.

Respectfully,

Luis Garcia

I deleted my initial response to Deborah, instead sending the following:

Matt came to our court after he was convicted of serious felonies. I did my best with him. I only wanted to learn things to help other veterans. I have no intention of contacting you again, and did not contact you after your first email. Sorry for your losses, Mark

Warriors suffer moral injuries for doing things they find unforgivable. Suicide kills so many brothers and sisters. The veteran suicide rate is more than double that of non-veterans. I will never understand the greater purpose of friends getting murdered or why veterans kill themselves. But I know why I cried on that stage. I was tired of pretending it didn’t hurt.

+++

We have rehabilitated several hundred veterans. So many were strung out and dying. They have reunited with family and friends, are living in safe housing, working good jobs and attending college. One veteran convicted of a serious felony assault graduated from our program and is in law school. Another is a successful screenwriter.

The weekend after I received Luis’s email, Kim and I hiked in a preserve near Murrieta, California. In the 1990s, a developer broke ground on an airport and 12,000 homes in these hills. A coalition of government and private agencies banded together and fought. The coalition won. Today, the Santa Rosa Preserve protects 15,000 acres. It is one of the finest woodland areas in California.

We took a break on a bench overlooking a valley. It was one of those beautiful days that brings everyone to California: 75 degrees, light breeze, no clouds. We sat under the shelter of an oak.

“I wanted to tell you some things,” I said. “About those nightmares I have.” I felt Kim’s eyes on my profile.

I told her about the warhead that landed near me in Iraq. “I just stood there like a dumbass. It sounded like a train. I should have hit the floor. In the dream it explodes, blows me to smithereens.”

“I can’t imagine,” she said.

“I’ve felt like I did something wrong,” I said.

“What? Why?”

“You know, I was a great officer,” I said. “Everything, all the things I did, were done great. If it happened under my command, I was responsible. Anything that went wrong was my fault — even if it really wasn’t. That drives you crazy. Humans fuck up all the time.”

Two red-tailed hawks floated in the air. I had beaten myself up for 16 years because I didn’t drop, didn’t yell, “Hit the ground!” to soldiers under my command. All of my psychological self-torture was based on not reacting to a roar I heard for maybe a half-second.

Kim was smiling. I was thinking how beautiful she was and how grateful I was to have her. We do everything together. She is always doing funny things to make me laugh, always going along on my adventures. How many wives would hang out with a group of felons to support their husband?

“You know I’d step in front of a bullet for you,” I said.

“I love you too,” she said, and we laughed.

“I wanted to tell you something else,” I said. “About some good friends. People I knew in Iraq.”

“OK,” she said.

“They’re Iraqis,” I said. “They’re all dead. They were great people. I should have shared their stories. They died because they worked with me.”

I felt Kim seeking the right words.

“Well, Your Honor,” she said. “You can tell me about them now.”

I never did go to the VA for nightmares. Maybe I am a hypocrite, telling others to do what I will not. But talking with Kim took away the nightmares’ power. I was right. PTSD scurries like a cockroach when exposed to the sunlight of truth.

On a wall in my courtroom is the tribute to Matt Stark that we displayed at his service. When struggling to do the right thing, I look to him. I don’t need to be a badass all the time. It’s OK to feel hurt. All I can do is try my best to help our veterans. That is my mission.

+++

M.E. Johnson is an author, California Superior Court judge, retired U.S. Army colonel and Iraq War veteran. For eight years, he has presided over the Riverside County Veterans Treatment Court. His webpage is www.mejohnsonauthor.com. He can be found on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook at @mejohnsonauthor.

What’s new on Task & Purpose

- After training together for years, Air Force pilots are watching Ukrainian friends fight for their lives

- An Army vet’s realization in Ukraine: ‘So horrible or heartbreaking that you can’t continue’

- ‘They own the long clock’ — How the Russian military is starting to adapt in Ukraine

- ‘We strike at night, when the Russians sleep’ — How Ukraine is stalking Russian armor with drones

- The leg tuck is officially dead and other changes coming to the Army Combat Fitness Test

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.