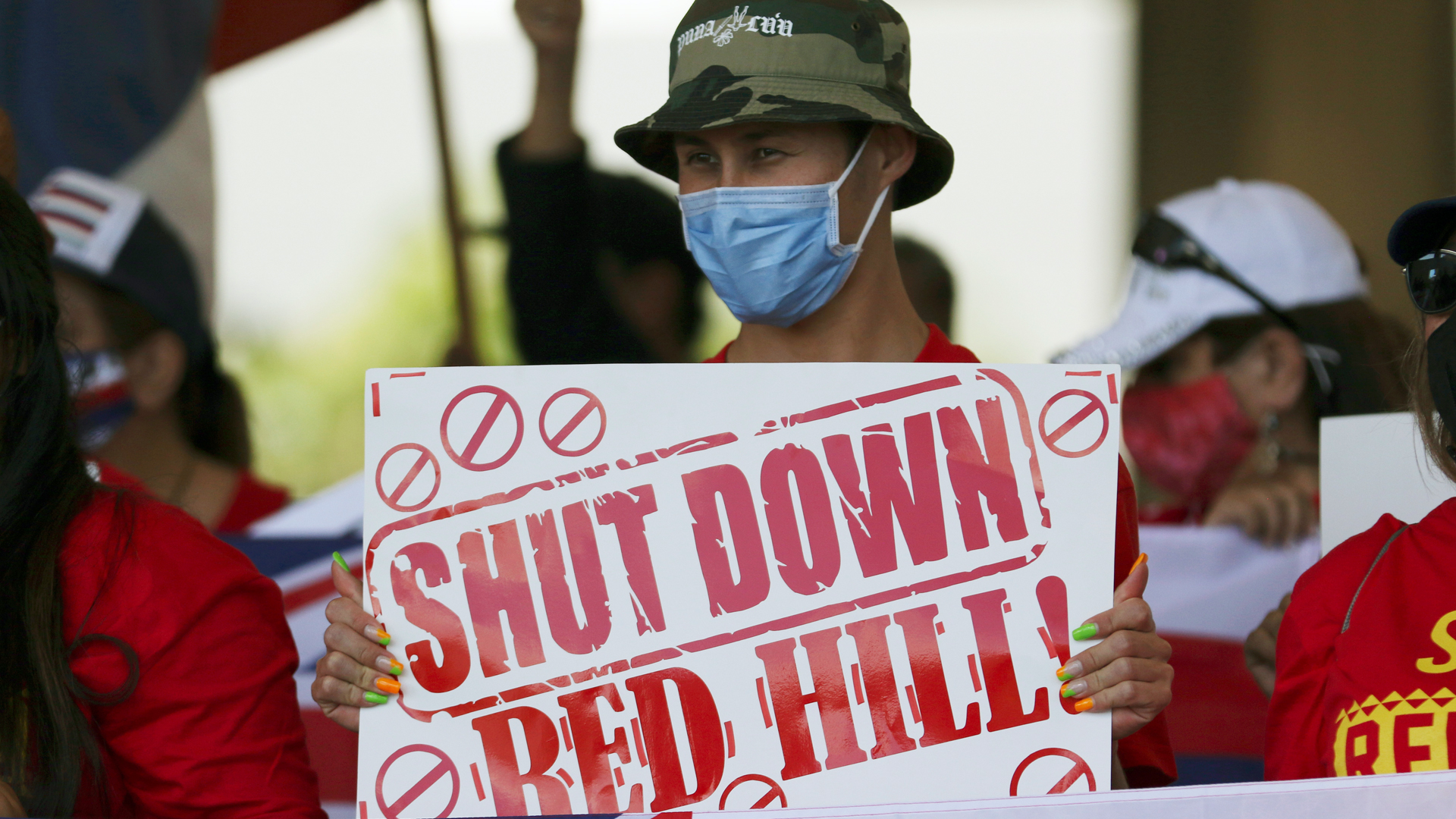

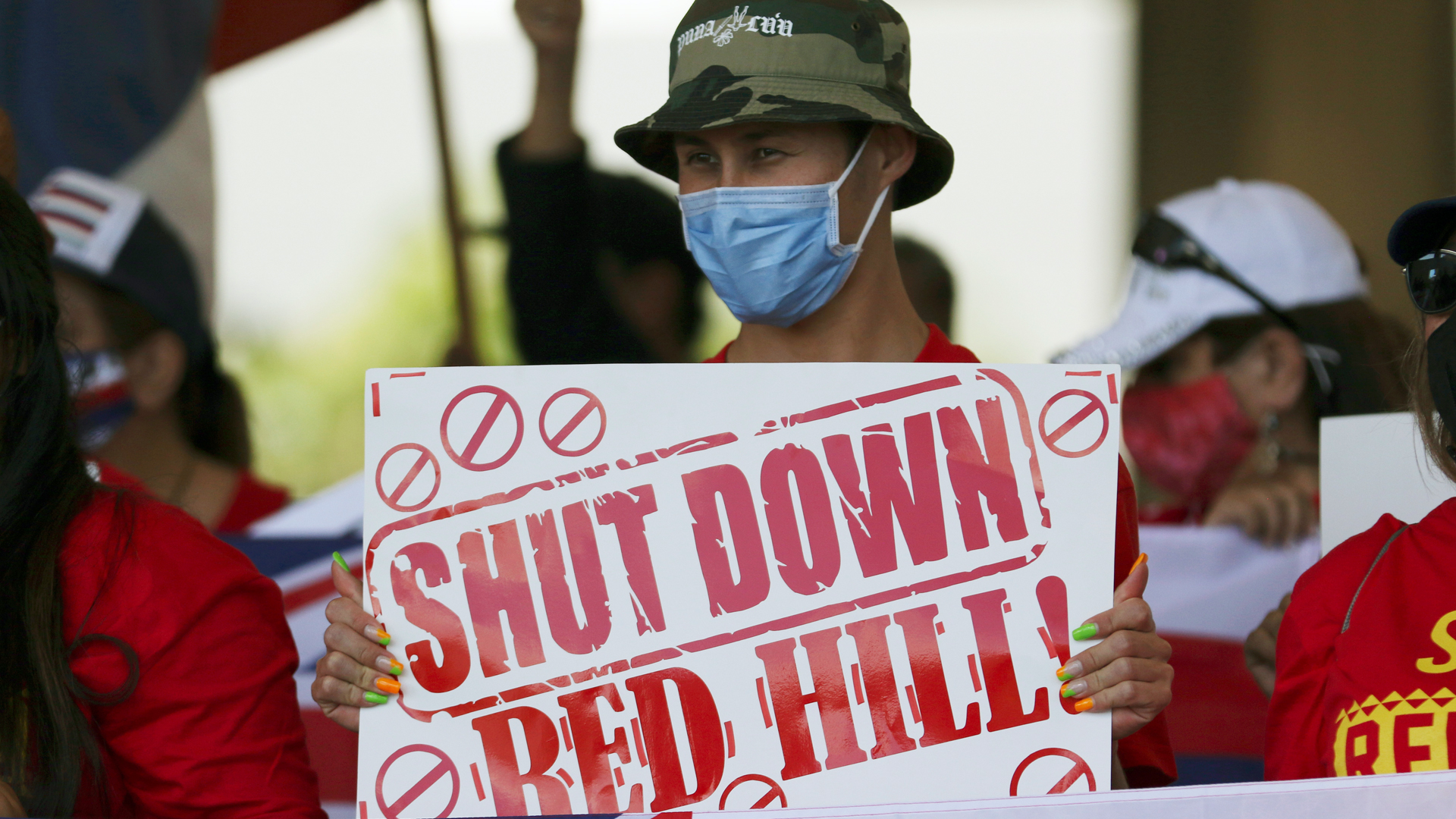

The Pentagon has decided to permanently close a fuel storage facility in Hawaii, months after a leak sickened service members and their families and forced thousands of them from their homes.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said in a statement on Monday that he made the decision to close the Red Hill bulk fuel storage facility in Hawaii after “close consultation with senior civilian and military leaders.” It won’t be completed anytime soon, however — the Secretary of the Navy, Carlos Del Toro, and the Director of the Defense Logistics Agency, Navy Vice Adm. Michelle Skubic, have until May 31 to provide Austin with a plan on how the facility will be defueled and closed, the statement says. After that, it will likely be 12 months before the process is completed.

Pentagon spokesman John Kirby announced the decision on Monday, saying Austin’s decision “is not considered by the department to be some sort of quick fix.”

“We have work to do — we know that — across the enterprise, with elected officials from Hawaii, and local organizations, and of course with our military families, many of whom have suffered as a result of that leak and that contamination,” Kirby said.

Residents of Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, first reported issues with their water at the end of November. Those issues included a chemical or fuel smell coming from the water in their homes, as well as an oily appearance in some cases. Within days the Navy was sending water samples to labs off of Hawaii to have them tested for contamination, but leaders have since been criticized for not communicating the severity of the issue early enough.

Capt. Erik Spitzer, commander of Pearl Harbor-Hickam, told residents on Nov. 29 that there are “no immediate indications that the water is not safe,” and said he and his staff were drinking the water. A week later, Spitzer came back with a statement to families that he “mistakenly felt the initial tests … meant we may drink the water.”

“We were wrong,” Spitzer said at the time. “I apologize with my whole heart that we trusted those initial tests. If there was one day I had a chance to do over, it would be that day. The words used in my notification were not the compassionate and validating words I wish were used, and I regret I did not tell our families not to drink the water. I am deeply remorseful.”

One Army family said they continued using the water for days when they likely shouldn’t have, because messaging from the Navy seemed to say the water was safe to use and drink. All four members of the family, including two small children, were hospitalized; their medical records listed possible water contamination as reasons behind their symptoms which included vomiting, diarrhea, severe migraines, and rashes.

“I volunteered for this, right?” Army Maj. Amanda Feindt told Task & Purpose. “I signed up, volunteering to serve our country after 9/11 happened. Me. And with that I know comes risk, and I know comes potentially being in harm’s way … but now I’m having to put my kids on a registry? My kids didn’t volunteer for this. My kids did not volunteer to be poisoned.”

Concerns from military families were laid directly at the feet of Navy leadership in various town halls with residents, when service members and spouses pressed leaders on what they knew and when. In one emotional moment, a military spouse told Navy leaders that whatever they’d known before the leak “became widely publicized and picked up internationally by the media is between you and your maker.”

“But now I ask with all eyes and ears on you that you fix this, and you fix it honestly, and I implore you to truthfully let us know how long we’ve been exposed so we can take precautions in the coming years and decades,” the woman, Lauren Bauer, said.

The leak in November is not the first time the Navy has been in the hot seat for fuel leaks. Local news reports identify leaks that have occured at Red Hill as far back as 2014. The November leak, however, was the last straw.

A week after reports emerged about contaminated water, the governor of Hawaii ordered the Navy to empty the Red Hill facility. But the Navy saw it differently; Secretary Carlos Del Toro said in a press conference that the governor’s direction was not an “order” but “a request and we are taking that very seriously.”

The Navy fought the emergency order, according to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, submitting “43 pages of objections.” But in January the Department of Health stood by the order, and the deputy director of the department issued “a final decision that upheld the order in its entirety,” according to the Star-Advertiser.

A fact sheet about the defueling process released on Monday says the Defense Department will work “in compliance with environmental safeguards,” and “complete environment mitigation efforts” for the Red Hill well and surrounding areas impacted by the leak. Moving forward, fuel storage will be redistributed “across the Indo-Pacific,” Austin said in a memo on Monday, which will “better position the United States to meet future challenges in the region.”

He also said the Pentagon “remains committed to mitigating the impacts” of the fuel leak in November, both to the civilian community and impacted military families. One of those primary concerns, of course, being potential long-term health issues that they or their children could develop because of the exposure to contamination.

Nataile Exum, an assistant scientist of environmental health and engineering at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told Task & Purpose it is “scary stuff when you start looking at health effects of petroleum in drinking water. I mean to be honest, will these parents ever know how this has impacted their kids and their immunological or their developmental growth? I mean I don’t think so.”

Asked on Monday about what the Pentagon will do to help families concerned about long-term health impacts, Kirby said the department owes “these families our very best attention to make sure that they get the medical care they need for the way in which this contamination has affected their health.

“We are 100% committed to that.”

What’s new on Task & Purpose

- What we know about the Russian general killed in Ukraine

- Where is the Russian air force? Experts break down why they might be hiding

- Meet Army Col. Daniel Blackman, the accidental face of romance scams around the world

- An urban warfare expert offers Ukrainians tips on battling Russians in close combat

- How the US can beat Russia in Ukraine without firing a shot

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.