The Medal of Honor, our nation’s most prestigious military accolade, has been awarded 3,530 times to 3,510 American servicemen and one servicewoman. Nineteen of the recipients have the distinction of having been awarded it twice. Of those 19, two were Marines: Dan Daly and Smedley Butler.

While Butler is known to most Marines for this rare achievement, he is better known outside of the military community for his late-in-life epiphany that during his 33 years of Marine Corps service, he and his men fought, killed, bled, and died more to shore up the profits of Wall Street than to defend the United States from foreign invaders.

“During those years, I had, as the boys in the back room would say, a swell racket,” Butler later said of his time in the Marine Corps in a book he wrote titled “War Is A Racket.” “I was rewarded with honors, medals, and promotions. Looking back on it, I feel I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was operate in three city districts. We Marines operated on three continents.”

Jonathan M. Katz’s new book, Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire follows the career of Butler from his posh early upbringing as the son of a powerful U.S. Congressman and member of a prominent Philadelphia Quaker family, and takes the reader on a whirlwind tour of his many military exploits around the world.

It’s understandable for those of us who were taught in history classes that America is not an imperialist country to be taken aback by the book’s title mentioning empire. I once thought the same. But as Katz travels in the footsteps of Butler, from Guantanamo Bay, Cuba to Shanghai, China and back, he illuminates how the Corps had been used in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries to make de facto colonies out of the Philippines, Nicaragua, Panama, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas, American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands. He also does a masterful job detailing our 1914 invasion of Mexico and the 1900 and 1927 occupations of China.

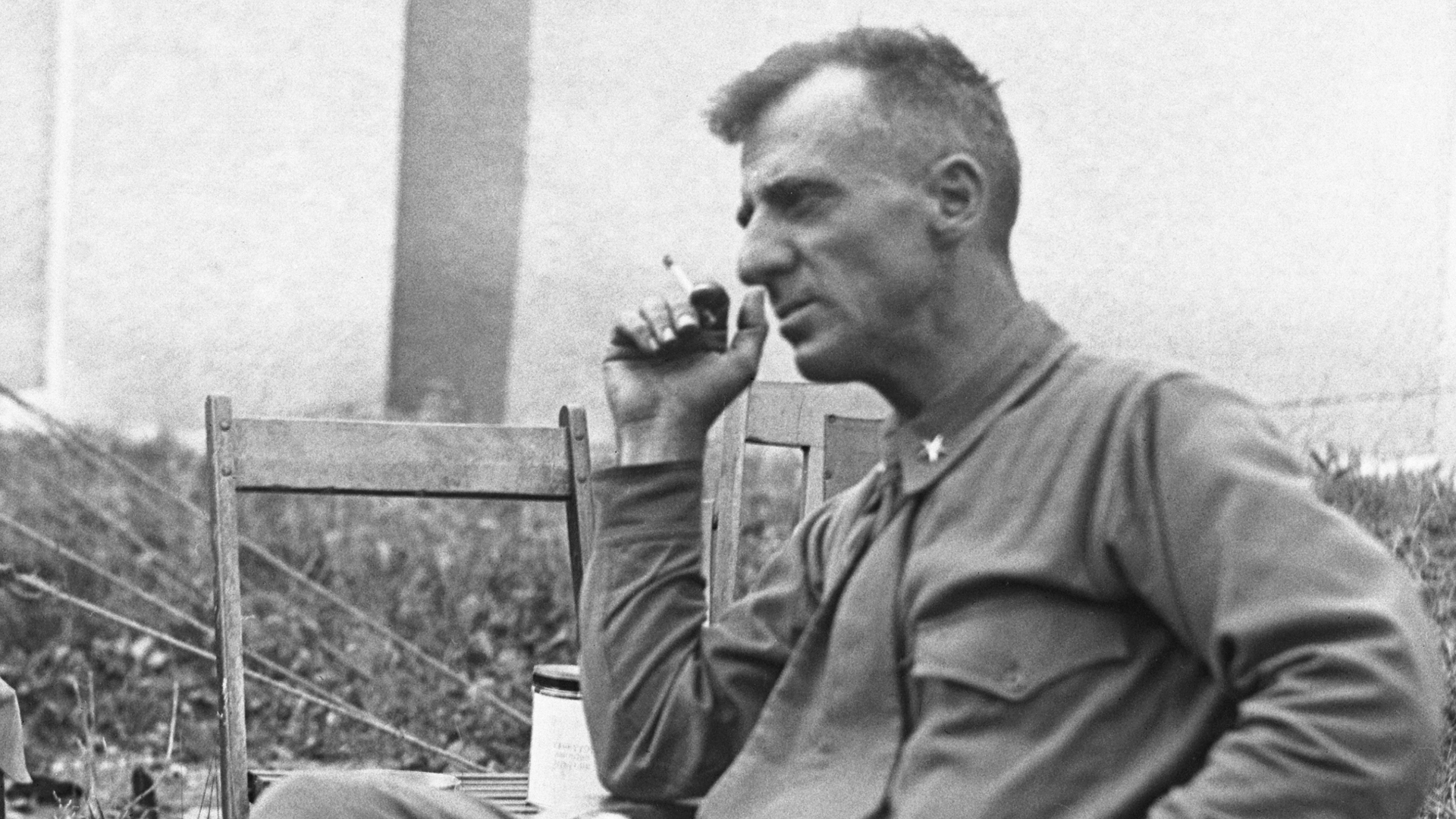

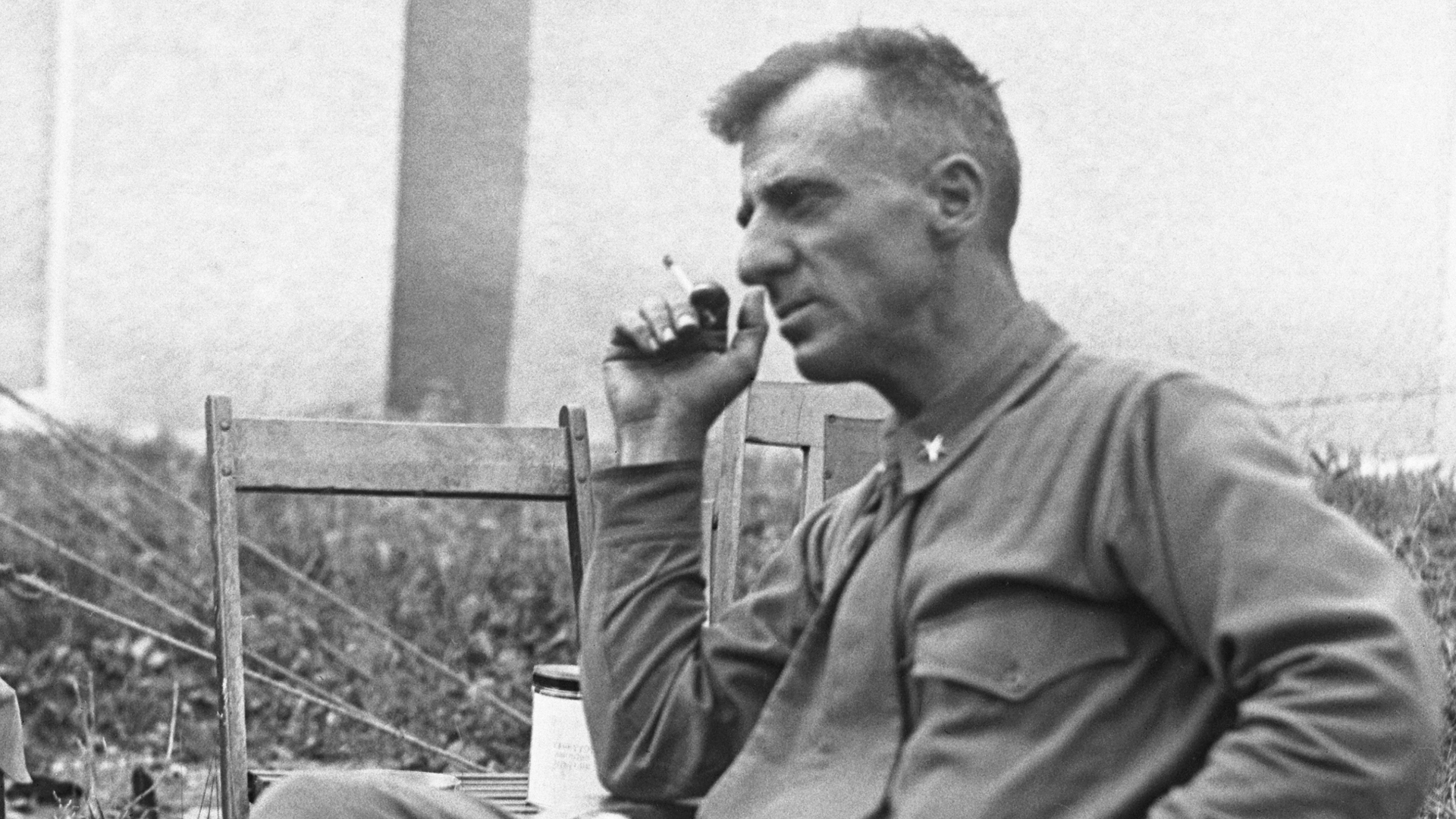

Smedley Butler was the Gen. Jim Mattis of his day – straight-talking, accomplished, and beloved by his troops. He was known nationally by his many nicknames: “The Fighting Hell-Devil Marine,” “Old Gimlet Eye,” “The Leatherneck’s Friend,” and “The Fighting Quaker.”

Unlike what one might glean from official U.S. Marine Corps history classes given at boot camp and Quantico’s officer candidate school, however, Katz provides a sober look at Butler. He describes a young man, who at 16 years of age, lied to join the Corps at the start of the Spanish American War, eager to prove his manliness to his Congressman father and doting mother. He describes a young officer who led his entire battalion straight into an ambush and then returned to base burning Filipino houses along the way home.

He tells of how a traveling Japanese tattoo artist gave 2nd Lt. Butler a gigantic Eagle, Globe, and Anchor (the classic Marine Corps signifier) chest tattoo – which immediately got infected, relegating him to 3 days of limited duty – and how soon after, Butler and company found themselves in Northern China attacking the city of Tianjin where Butler got shot in the right thigh. Katz also tells the story of how the Marines looted the city of a lode of silver bullion with an estimated value of $11 million in today’s dollars – which was quickly sold to a J.P. Morgan representative in Shanghai; and how Butler, who turned 19 on that campaign, was promoted to the rank of captain, contracted typhoid fever, and returned to San Francisco as a 98-pound ghost.

Beyond the fascinating and familiar portrait of Butler, Katz also excels at depicting the domestic and international politics of the Banana War era and how the United States government and large corporations worked hand in hand to create a string of U.S. outposts around the world and overthrow indigenous governments for the purposes of seizing land, controlling exports, and enriching shareholders.

From Panama to Honduras, Nicaragua to Haiti, Katz reveals how the Marine Corps was used to provide muscle as Wall Street financial institutions and U.S. corporations imposed their will where they invested – rigging elections, violently stamping out dissent, installing dictators, and training and militarizing police forces to keep them in power. He also details Butler’s navigation as a Northerner and a Quaker through the cultural climate of the Corps, which was led mainly by Southern-born officers inculcated with white supremacist world views.

One of the book’s most interesting aspects is how Katz shows how U.S. policy and our frequent military interventions in the late 1800s and early 1900s created many of the problems still present in Mexico, Central America, and many Caribbean countries.

Katz also captures the evolution of Butler’s thinking as he left active duty, and how he spent his final decade on Earth working to restrain and dial back the same military forces that he had personally helped unleash upon the world. As fascism engulfed Europe, Butler sought to atone for his past transgressions and engaged in anti-war, anti-imperialist, and anti-fascist efforts. Katz covers Butler’s advocacy in 1932 on the behalf of the impoverished World War I veterans of the Bonus Army before they were driven from Washington, D.C. with tear gas, by tanks, and at bayonet point by Army troops led by Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Katz also tells the story of how Butler was recruited in 1934 by agents of Wall Street financiers to lead 500,000 American Legionnaires in a coup to overthrow the Government of the United States and install a fascist dictatorship.

He goes on to detail Butler’s 1935 blistering condemnation of corporate greed and war profiteering in his book War is a Racket fully 26 years before President Eisenhower warned of the dangers of the military-industrial complex. In this sense, Butler was a man way ahead of his time.

Those who served during the invasion and occupation of Iraq or any of the bewildering two decades in Afghanistan will see many parallels of wars sold to the American public based on false information and the minimization of the many strategic failures of senior political and military leaders. Katz’s realism may shock many readers, but they would be well served to join him in pulling back the curtain, tipping over the jugs of institutional Kool-Aid, and taking a long, cold hard look in the proverbial mirror. Like watching a train wreck in slow motion, this is a raw historical perspective that will both fascinate and unsettle.

What’s hot on Task & Purpose

- A judge ordered a man convicted of sexual assault to join the military or go to jail

- An Army spouse used a $30 device to track down a shady moving truck driver

- The Navy is still looking for the best use of its ‘little crappy ships’

- Here’s why the Marine Corps must do more to keep its best female Marines in uniform

- These soldiers cleared a path through 145 unexploded artillery rounds so senior officials could visit a building

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.