Between inflation, high gas prices, and rising housing costs around many bases, it has not been a great year on the economic front for many service members. That’s why recent news that 489 enlisted airmen may face a pay cut in the next few months seemed to add more pressure to many already strained pocket-books.

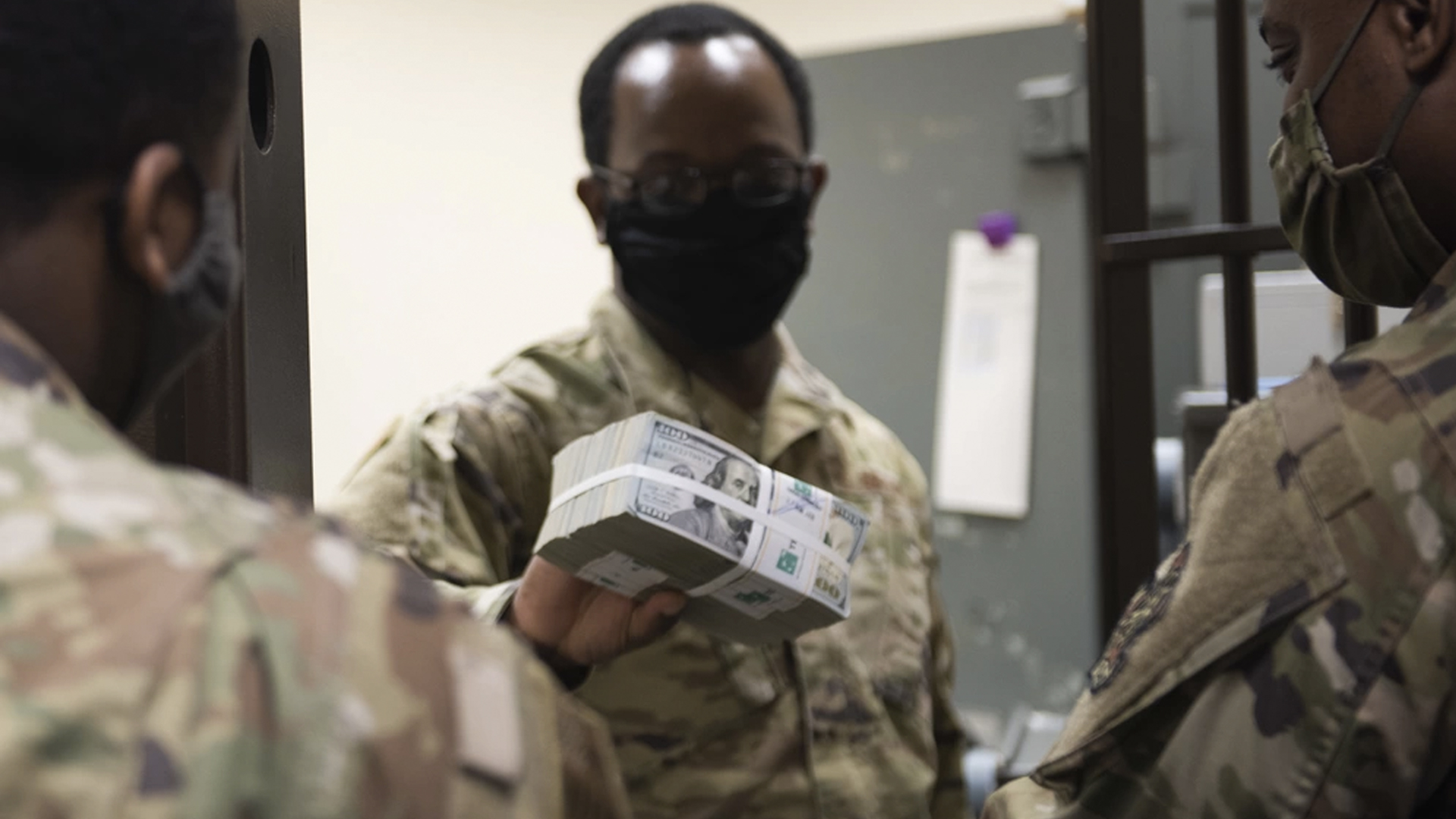

Airmen in 44 enlisted career fields which receive special duty assignment pay (SDAP) are set to receive less special pay than usual — a drop of anywhere from $75 to $450 a month, as first reported by Air Force Times last week. Those fields include some of the most dangerous or difficult jobs in the service, including pararescuemen, combat controllers, first sergeants — who serve as mentors for younger airmen — and basic military training instructors. Also included are recruiters, who are already having a tough time amid one of the most difficult recruiting years in recent memory.

“With high gas prices and cost of living in some of the biggest cities, we are feeling less motivated,” wrote one recruiter in a message about the SDAP drop posted to the popular Facebook page Air Force amn/nco/snco in June.

The 30,845 airmen who are still due to receive SDAP in 2023 are 489 fewer than the 31,334 airmen who received it in 2022, which in turn was 367 airmen higher than 2020’s figure of 30,976 airmen on SDAP, according to budget documents.

Fiscal year 2023 begins on Oct. 1, but it could still take months before the Air Force’s budget is signed into law. Last year President Joe Biden signed the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act on Dec. 27, nearly three months after the start of the 2022 fiscal year.

How much of an impact the SDAP drop may have on airmen and their families depends on the finances of individual airmen, but some have to make every cent count just to put food on the table. The U.S. Census Bureau found an average of 23% of active duty respondents with children reported not having enough to eat sometimes, or often, between April 2020 and February 2022, compared to 16% of all active-duty respondents and 11.9% of all U.S. households with children.

“If you’re in the Pentagon, you get by, but the enlisted guys living paycheck to paycheck may not,” said retired Army Maj. Gen. John Ferrari, a nonresident senior fellow and defense budget expert at the American Enterprise Institute.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Beyond the monetary cost of losing up to $5,400 a year in income, there is also the personal sting of losing a benefit that airmen were promised in exchange for performing “extremely difficult duties that may involve an unusual degree of responsibility in military skill,” as the Air Force described SDAP jobs.

“Whether it’s $1 or $1,000, It sends the message that this assignment is not as respected as it used to be,” said Katherine Kuzminski, a senior fellow and director of the Military, Veterans, and Society Program at the Center for a New American Security. “That’s not the message the Air Force is trying to send … they are dealing with a budget shortfall.”

Congress, the Air Force and the military in general are trying to soften the blow of inflation on service members by including a 4.6% military-wide pay raise in the 2023 budget request. The Air Force also included a 4.3% increase in basic housing allowance in its proposal, and a 3.4% bump in basic allowance for subsistence to offset the cost of groceries, Military.com reported.

Even so, the bumps may not be enough to offset the 8.5% inflation reported in July, Kuzminski pointed out. Air Force officials often say that airmen are the service’s “most important asset,” so how did the Air Force come to a point where it has to take $1.5 million in special pay from airmen who do some of the most difficult work in the business?

In the complicated process that is balancing the defense budget, it is difficult to pin down an exact answer, but experts pointed to several factors that may have influenced the decision. Those factors include the long lead time for planning the annual defense budget; insufficient methods for measuring inflation; and the sheer number of trade-offs and decisions that have to be made to create an annual Air Force budget.

“You have to nip a little here and a little there and you may not even remember you did it,” said Ferrari, who was personally involved in many similar decisions during his time in the Army. “It’s not like people set out to be malicious … but there are so many hundreds of decisions that have to be made where you try to make the best of bad choices, so you hope you don’t do anything irreversible.”

It’s not uncommon for SDAP levels to fluctuate from year to year depending on the needs of the Air Force. Still, this drop seems to come at a tough time for many service members. One of the most important reasons why this happened is because Air Force planners made their decision to cut SDAP for some airmen months before inflation became as serious a problem as it is today. Officials discussed how to handle a $3 million shortfall in special duty pay as far back as last November, a service spokesperson told Air Force Times. Keep in mind that a major trigger for today’s economic turbulence was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which began on Feb. 24.

Technically, the pending SDAP cut has also been public information for five months now. The Air Force’s fiscal 2023 budget estimates for personnel were published in April, though it’s not surprising the implications of the document slipped past many people.

“The budget documents are hard to decipher,” Ferrari said. “And so now staffers on the Hill are saying ‘hey wait a minute.’”

The Air Force could have been more proactive in communicating the implications of its budget estimates to service members affected by the SDAP cut, Ferrari and Kuzminski said. Ferrari said it was also curious that the Air Force did not include SDAP on its unfunded priority list, which is a document outlining for Congress all the things the Air Force wants to buy but could not fit in its budget request.

“The unfunded priority list is where uniformed leadership mentions things they’re worried about,” Ferrari explained.

Instead, much of the $4.6 billion requested on the Air Force’s unfunded priority list was split between weapon system sustainment, building and restoring facilities and buying new aircraft like F-35 fighter jets and EC-37 electronic warfare platforms. The $1.5 million cut from SDAP is a drop in the bucket compared to the $979 million requested for EC-37s and the $921 million requested for F-35s, so it may be tempting for service members to feel undervalued when compared to expensive equipment.

“It is a valid concern,” said Ferrari, who pointed out that budget planners spend much of their time making trade-offs between manpower, training and modernization, each of which is essential and none of which can be fully funded without taking funds away from another.

“It’s a delicate balance where Air Force leaders try to make the least worst choice,” he said.

One of the Air Force’s budget planners, Vice Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin, seemed to admit as much during a live-streamed chat last week with the top enlisted airman, Chief Master Sgt. of the Air Force JoAnne Bass.

“It’s tough to look at the airmen and say, ‘Yes, we have tough economic times, but I’m going to cut your pay anyway,’” he said, according to Air Force Times. The general said officials “lose touch” with what service members need while creating budgets.

“We carve out little bits of money here and there to afford that next F-35, or to be able to do that development and testing here. But that doesn’t resonate very well,” he said. “We all have work to do to understand the impact on recruiting and retention.”

Even so, a massive chunk of the military’s budget does not go to F-35s, submarines or other expensive equipment, but to the professional workforce. Mackenzie Eaglen, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, pointed out in an op-ed for Defense One that in 2021, $300 billion of the Pentagon’s $720 billion defense budget went to civilian and military pay and benefits, which must stay competitive with civilian pay and benefits in order to keep the military staffed.

“There’s the public perception that the Air Force spends all its money on platforms, where in reality they spend quite a significant bit on human capital,” said Kuzminski.

On top of that, another 30 to 40% of the military’s overall budget went to operations and maintenance of equipment, Eaglen wrote. Inflation eats up another chunk of percentage points every year, which leaves only 10 to 15% of the military’s overall budget to spend flexibly “for meaningful change or truly strategic choices,” she said.

“The fixed and fenced costs throughout the U.S. defense budget will prevent even the most well-intentioned Pentagon team from achieving better purchasing power for defense strategy outcomes,” Eaglen added. In a separate analysis for AEI, she pointed out that the military also spends money on efforts that duplicate civilian sector programs, like cancer research, education grants for state and local entities, running schools and bolstering grocery chains.

“The cost of people has been rising faster than inflation for the last 20 years because of wars, needing professionals, because the military is a risky business, and troops sacrifice to serve,” Eaglen told Task & Purpose. “We pay more for a smaller force … but many enlisted troops are on food stamps.”

Part of the problem is that military officials at this point do not have the most capable tools for predicting or adjusting to rapid changes in inflation. Pentagon leaders wrote in a May letter to Congress that the Department of Defense does not collect actual inflation-related data when executing a budget, and while the department does monitor overall spending levels, inflation “is not tracked separately … primarily because inflation is only one of the factors that can impact the cost, schedule and performance of our programs and activities,” the Pentagon wrote.

U.S. Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.) and Sen. Jim Inhofe (R-Okla.) were not impressed by the Department of Defense’s efforts to measure inflation.

“Overall, we are concerned that the Department is not taking a proactive stance to mitigate the harmful effects of inflation,” they wrote in May. “At the very least, they should be collecting necessary data, establishing a governance framework and conducting regular touchpoints with all stakeholders. In particular, it doesn’t seem that the Department has a good grasp on how inflation is hurting our service members and their families — and how this is in turn impacting recruiting and retention.”

Eaglen and Ferrari noted in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal that the House and Senate have added $7.1 billion and $21.2 billion to their respective defense bills, but it still may not be enough to clear inflation for military families.

“Having already added more money to the defense budget than President Biden requested, Congress will have to appropriate even more to save America’s troops from the Defense Department’s negligence,” they wrote.

There may be changes on the horizon. The Pentagon will soon conduct its 14th Quadrennial Review of Military Compensation, which is a study the military conducts every four years “of compensation principles and concepts for members of the armed forces,” according to a Pentagon website. The top enlisted airman, Chief Master Sgt. of the Air Force JoAnne Bass, told Air Force Times on Tuesday that she and her counterparts in the other services want to take “a holistic look at our military compensation, to include health care, for our service members and their families.”

Bass acknowledged that the military needs a better way to calculate how to help troops keep up with inflation, rather than wait too long for an annual pay raise which, “is not helpful to anybody,” she said.

Still, it could be several more years before the quadrennial review is complete, so how can the military be more responsive to the economy’s rapid changes in the meantime? Bass proposed looking into artificial intelligence to help predict how families should be paid. She also said that she and her boss, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles ‘CQ’ Brown Jr., “are beating the drum when it comes to the pay, the benefits, the quality of life and quality of service of our airmen.”

It may not be too late for Congress and the Air Force to reverse course on the SDAP cuts. Ferrari said that the Air Force may still be able to go to Congressional committees and ask for an adjustment, and even after a bill is signed into law, the Air Force can ask for reprogramming to plug the $1.5 million gap in SDAP.

Considering the scale of the Air Force’s $170 billion dollar budget request for 2023, it’s not difficult to imagine $1.5 million being misplaced. But for the 489 affected airmen whose budgets are much smaller than that of the Air Force, it may be difficult to fill that gap.

“As [planners] get to the end of these budget processes and there are large bills that need to be paid, sometimes you go to many different accounts and you don’t fully anticipate the effect downstream,” Ferrari said. “Nobody sets out to do anything bad, but it’s a big institution and hundreds of decisions get made … in this case, it’s not irreversible. They can still fix this.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- The Navy’s ‘ghost fleet’ is growing

- Watch Iran try (and fail) to kidnap an American drone boat at sea

- Little Debbie snacks are being retired from service at military commissaries

- We salute the airmen who got 300 Chick-fil-A sandwiches flown in to feed their buddies

- Watch an Air Force pararescue vet fight off an alligator attack with his bare hands

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.