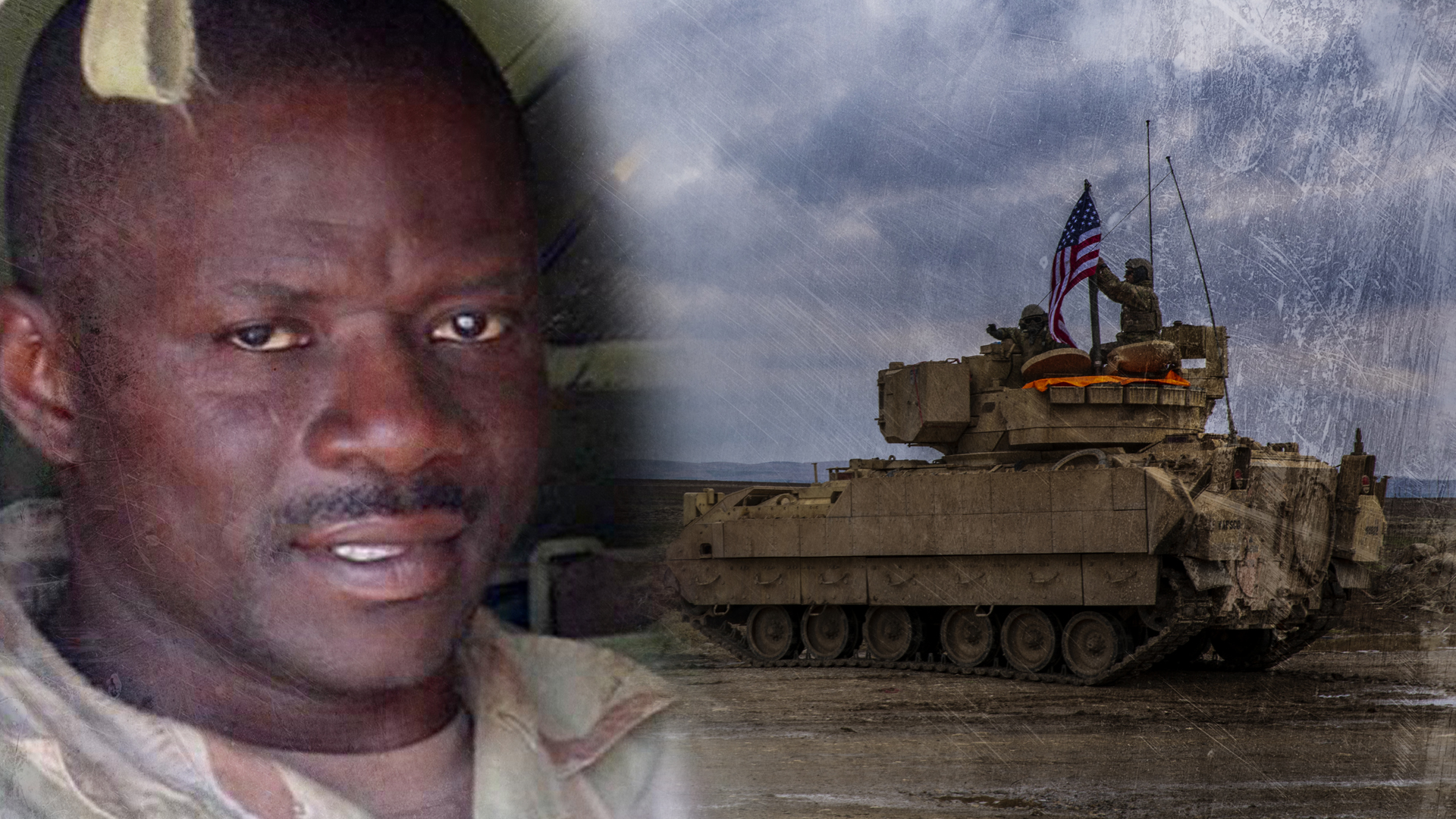

On Oct. 17, 2005, Sgt. 1st Class Alwyn Cashe walked through fire again, and again, and again, all to save his soldiers who were trapped in a burning Bradley Fighting Vehicle in Iraq.

Cashe, who died weeks after sustaining major injuries from the improvised explosive device (IED) that engulfed his vehicle in flames, is set to posthumously receive the Medal of Honor on Thursday. The journey to have Cashe’s posthumous Silver Star upgraded has been over a decade in the making. In a series of six videos posted by the 3rd Infantry Division on Monday, Cashe’s soldiers told his story in their own words. They remembered him as a dedicated leader who put in the time to really know them, who always had a joke at the ready, and who even in their darkest moment was concerned with their wellbeing over his own.

Born in 1970, Cashe enlisted in the Army after high school in 1989. In 2005, he deployed to Iraq with the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division — his second tour there. Soldiers who served with him in 1st Platoon, Alpha Company, remember a leader who was “calm and cool” and cared for each of his troops individually. He was like a “big brother,” said Gary Mills, the 2nd Squad Team leader at the time of Cashe’s death. He would never “tell me to do something he wouldn’t do,” Mills said. Cashe “always had our welfare in his interest,” retired Sgt. 1st Class Douglas Dodge said.

Maj. Leon Matthias, Cashe’s platoon leader, first met Cashe in Iraq. Matthias recalled being a “young new lieutenant” who was champing at the bit to get into combat while Cashe, who had deployed before, approached things in a more level-headed and methodical way and who, based on the video interviews with his fellow soldiers, appeared to be every bit the seasoned staff noncommissioned officer.

“The first conversation I remember having with him, I was saying, ‘Hey sergeant, cigarettes are bad for your health.’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, so are effing lieutenants,’” Matthias laughed in one of the video interviews.

Matthias said he was struck by how well Cashe knew his soldiers — their strengths, weaknesses, and whatever challenges they were facing — and how much he cared for them. He “talked about them like they were his children,” he said. Dodge who was a squad leader under Cashe, recalled once having marital problems while he was deployed to Iraq. While they had some — very rare and brief — down time, Dodge said Cashe “called my wife from Iraq and talked to her at length.” He then came and told Dodge to call her as well.

“‘I know you’re having problems, and I want you to have your head clear while you’re out here doing stuff,’” Dodge recalled Cashe telling him. “At the time I was kind of angry because I was tired, I just wanted to sleep. But he had taken his time when he could have been sleeping … to try to take care of me. And that’s something I’ll never forget.”

‘We were all on fire’

Cashe and his soldiers were in “a hot spot” for enemy contact. Dodge said they were engaged with small arms fire or improvised explosive devices (IEDs) three or four days out of the week. Cashe’s burden, Matthias said, was to “bring everyone home.” It drove “everything that he said and did.”

“Every ramp brief he would say, ‘It’s going to be hard coming home without the guys you came here with.’ Every ramp brief,” Dodge said. “Who would have known he would have been one of those people?”

On the night of Oct. 17, 2005, 1st Platoon set out to conduct a route clearance patrol ahead of another convoy coming through the area the next day. The weather was “really, really bad,” Matthias recalled. There was a dust storm moving past Forward Operating Base Mackenzie. While the platoon originally had three Bradley Fighting Vehicles ready to leave the base, mechanical issues resulted in just two leaving.

Matthias, the platoon leader, would typically ride in the first Bradley of a convoy, but he’d just returned from leave and Cashe insisted that he go in the lead vehicle instead. Because they only drove out with two Bradleys instead of three, they didn’t have all of the soldiers they’d planned to bring, but it was supposed to be a relatively simple patrol, Matthias said. They didn’t even plan to dismount. It would be “a standard drive down to the bridge, make sure the route was clear, hang out for a bit, and drive right back.”

The platoon moved out slowly. Mills recalled being in the back of one of the Bradleys, talking with the other soldiers and “getting our mind into what was going to happen.”

“Then, boom,” he said.

Cashe’s Bradley at the front of the convoy hit an improvised explosive device. Dodge, who was in the vehicle with Cashe, said he remembers hearing the very distinct sound of the IED before he was thrown into the ceiling of the vehicle and knocked unconscious.

When the Bradley Fighting Vehicle struck the IED, the fuel cell ignited, immediately engulfing the vehicle — and all of the soldiers trapped inside — in flames. The explosion “severed the cargo hatch opening mechanism,” according to the videos, and the driver, Spc. Darren Howe, was also knocked unconscious and unable to release the hatch.

Dodge said that when he awoke after an unknown period of time, “we were all on fire.”

Matthias, in the second Bradley, said he saw Cashe and another soldier immediately jump out of their vehicle. Initially, Cashe was only slightly injured, according to his Silver Star citation, but he, and the other soldiers, were drenched with fuel. After Cashe helped pull Howe out of the driver’s hatch, he immediately ran back to the burning vehicle.

Inside, soldiers were screaming and attempting to get out. The first thing Dodge remembers after waking up is “the pain from being on fire,” which he immediately tried to extinguish as best as he could. He heard the other soldiers yelling for help and he reached into the dark to find some way to open the back hatch but to no avail.

“That’s when I saw Sgt. Cashe at the back of the Bradley,” Dodge said. “And I looked at him and it was very surreal: He had his helmet on, his body armor on, and his boots on, but he didn’t have anything else on because it had been burned off of him. The only thing he asked me was, ‘Where are the boys at?’ I just kind of looked at him and looked at the Bradley, and he said, ‘We’ve got to get the boys out.’ And he just instantly started climbing in.”

As Matthias continued calling back to headquarters to get help, Cashe began pulling his soldiers out, one by one, despite being on fire himself. In a video interview Matthias said that as the chaotic situation unfolded, he couldn’t tell if the patrol was taking incoming fire. Details from that day emerged slowly, with new information coming to light that showed the patrol was caught in an ambush and took small-arms fire in addition to the IED strike.

“The true impact of what he did that evening was not immediately known because of the chaos of the moment,” Maj. Gen. Joseph Taluto, one of Cashe’s commanding officers and an advocate to see his Silver Star citation upgraded to the Medal of Honor, told the Los Angeles Times in December 2014.

Nonetheless, Cashe went back “over and over again,” Matthias said. It “felt like forever” before another team arrived to help. Two helicopters arrived to evacuate the wounded, and even though Cashe was the most severely burned — 72% of his body was covered in third and second-degree burns — Mills said he wouldn’t stop asking how everyone else was.

And when it was time for him to be loaded onto the helicopter, Cashe refused to be carried. He wanted to walk off the battlefield.

‘How are my boys?’

Once Cashe was loaded onto the medevac with the rest of the wounded, they were flown to the nearest military hospital in Iraq. Dodge recounted the medevac flight to Balad Air Base where the wounded were triaged and treated. “Sgt. Cashe, the whole time there, I could hear him yelling ‘how are my guys? What’s going on with them? Where are they at?’ Kind of refusing, almost, treatment until he knew that we were all being taken care of.”

For the soldiers who were there, the following hours and days are a blur, with some of the soldiers placed in medically induced comas to help them recover from their injuries. But from the moment they stepped off on patrol, through the IED strike and ensuing ambush, and aboard the medevac flight to Balad, and then on to an Army hospital in Texas, and up until the end, Cashe and his soldiers remained together.

An Air Force doctor who treated him, Maj. Mark Rasnake, wrote in a letter home that Cashe is “the closest thing to a hero that I likely will ever meet.”

“People use the word ‘hero’ too much,” Rasnake wrote. “We have cheapened it. We use it to describe football players and politicians. We even use it derisively at times to describe people we think are being too eager or self-promoting … Most of us will serve our time here with pride without ever truly earning that title. The man I met last night deserves to be called Hero.”

When Mills woke up at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas and saw his family, the first thing he said to them was, “I didn’t know that they allowed family in Iraq.”

“I didn’t know I was in Texas,” he said. “I did not know — they were like, ‘No it’s four days later.’”

While the doctors and his family told Mills he wasn’t allowed to go visit the other men, he did anyway. He had to see Cashe. It was “crazy” to him because, despite the pain and injuries they were both dealing with, he said Cashe “still had jokes” and was making sure he was okay.

“It’s like man, even in our baddest moment, it [didn’t] matter about him, it mattered about everybody else,” Mills said.

Just five days after the explosion, the first soldier injured that day succumbed to his wounds. Staff Sgt. George Alexander, 34, was the 2,000th soldier to die from combat in the Iraq War. He was followed by the platoon’s medic, Sgt. Michael Robinson, who was 28 years old, just four days later. The young soldier who was driving the Bradley at the time of the explosion, Spc. Darren Howe, died on Nov. 3. He was 21 — he’d enlisted in the Army on Sept. 10, 2001.

Cashe died five days later on Nov. 8. His final moments were a testament to his character and his stalwart leadership. As he lay in a hospital bed, his sister recalled Cashe asking, “How are my boys?

Since then, advocates including Cashe’s family, and lawmakers, have called for his Silver Star to be upgraded to the Medal of Honor. That fight looked to be nearing an end last year, when lawmakers passed legislation waiving the required time limit in which someone must receive the medal, approving him for the award. In December 2020, President Donald Trump signed that legislation into law, clearing the path forward to have Cashe posthumously awarded the nation’s highest award for valor.

But the announcement never came. In January, the White House team coordinating the Medal of Honor announcement determined that a potential ceremony wouldn’t come until after President Joe Biden took office. And since then, Cashe’s family and their supporters have been waiting.

That wait finally came to an end when the White House officially announced the upgrade on Friday.

While the rest of the world has learned who Cashe was and what he did that day in Iraq, his soldiers have always known exactly the kind of leader they had. In the videos posted on Monday, Dodge recalled one moment when he and another squad leader disagreed with Cashe on something. Cashe directed them to their company first sergeant who sat Dodge and the other squad leader down, and told them, “You guys don’t understand what he does every day to try to give you guys time, just to have even an hour for yourselves.”

“He wasn’t in our faces, he wasn’t like, ‘Look what I did for you guys,’” Dodge said. “It was just unspoken. He just did it because he cared.”