In the early afternoon of Oct. 4, 2017, a team of U.S. and Nigerien partner forces were pinned down by an overwhelming enemy force in Tongo Tongo, Niger — stuck without backup or the possibility of medical evacuation. Four Americans were killed. The cover-up began almost immediately.

That’s the finding of a new documentary from ABC News on Hulu, “3212: UN-REDACTED,” which closely chronicled attempts by senior military officials to cover up what really happened that day, and to protect higher-ranking officers who were at fault.

The attack by Islamic State militants in Niger resulted in the deaths of four Army special operators — Sgt. 1st Class Jeremiah Johnson, Sgt. LaDavid Johnson, Staff Sgt. Bryan Black, and Staff Sgt. Dustin Wright — and four Nigerien soldiers. It was a shock to a nation who, in many cases, didn’t even know the U.S. had troops in the African country.

While speaking to the press at the Pentagon on May 10, 2018, Marine Corps Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, the commander of U.S. Africa Command, stated in his opening remarks that he took “ownership for all the events connected to the ambush.” The “responsibility is mine,” he said. But that sense of ownership quickly dissipated as the official who carried out the investigation — Waldhauser’s own chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Roger Cloutier — laid out a list of problems the investigation had found.

The problems weren’t with AFRICOM, officials claimed, or even with the chain of command that oversaw an operation that placed American soldiers in a situation where they had little to no support and were vastly outnumbered by enemy militants. Instead, the blame was laid at the feet of the special operators themselves.

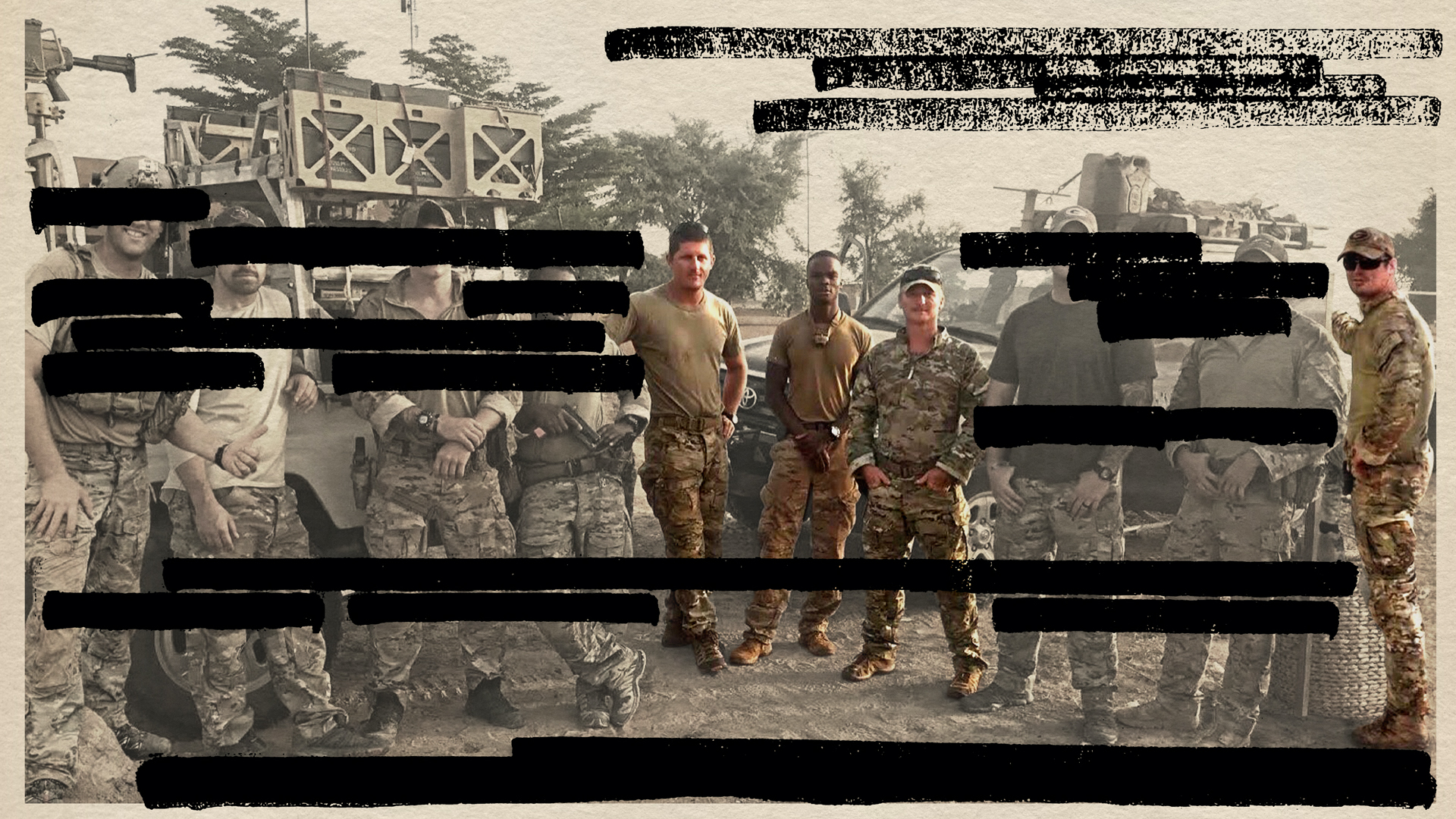

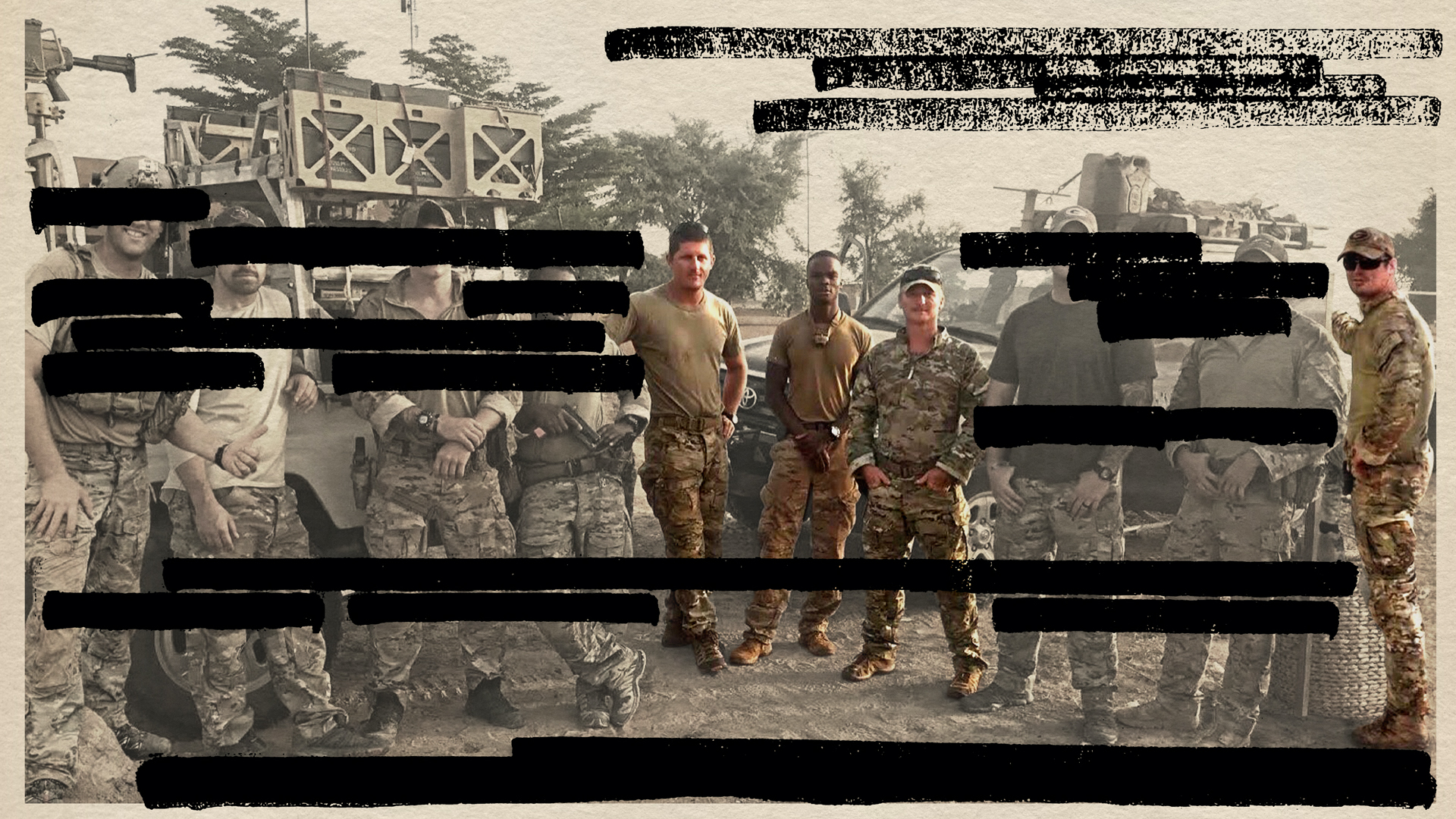

The soldiers of Operational Detachment-Alpha 3212 had not completed “basic social-level routine tasks” ahead of the mission, Waldhauser said, adding that they “inaccurately portrayed” the intent of a mission they carried out the day before the ambush. The actions of the soldiers of ODA 3212, Waldhauser claimed, were “not indicative” of the “fantastic job” U.S. special operators do in Africa.

U.S. AFRICOM briefing on the Tongo Tongo, Niger ambush:

Elsewhere across the country that day, outside of that briefing room at the Pentagon, family members of the four fallen soldiers watched as Waldhauser and Cloutier described their loved ones as inadequately prepared soldiers who had essentially gone rogue on an unauthorized mission to capture an ISIS target.

“From the beginning, everything was negative about the team,” Arnold Wright, Staff Sgt. Dustin Wright’s father, said in the documentary. “Basically what they said was the team leader lied in the brief that he submitted to higher about the mission.”

They felt in their gut that what they were hearing wasn’t correct. And now, more than three years after that May 2018 briefing at the Pentagon, the families know the truth.

“3212: UN-REDACTED,” the culmination of years of investigative reporting by ABC News’ James Gordon Meek, pieces together a story that’s entirely at odds with the Pentagon’s version of events of what happened that day in Tongo Tongo. A story of soldiers who followed orders from senior officers who were continents away, after concerns about the mission’s safety voiced by the commander on the ground were overruled. A story about families who say they were deeply misled by Army officials and lied to on a number of occasions. A story about senior military officials who sought to cover their tracks and allowed more junior leaders to take the fall for the mission’s outcome — including an Army officer who was back in the United States with his wife while his baby daughter was being born.

The documentary highlights the excruciating and raw pain of each of the families of the fallen. In one particularly heartbreaking moment, Myeshia Johnson, the wife of Sgt. LaDavid Johnson, is shown lighting a candle on her daughter’s birthday cake. The family of four sings happy birthday as she picks up the little girl and tells her to blow the candle out.

While they sit down at their kitchen table to eat cake, Myeshai sets a photo of LaDavid next to her.

“I don’t got anything to make him sit up,” she says.

“Daddy can sit on Shay Shay’s lap,” one of the children responds. Each day, the kids still ask when their father is coming home, Myeshia says.

“‘Mommy, when Daddy coming home? When Daddy coming home?’ And I have to tell them, ‘Daddy’s not coming home. Daddy’s in Heaven now. You can see Daddy in your dreams,’” Myeshia says. “And when I’m dead and gone, I’m going to reunite with my husband. He’s going to be waiting for me.”

Near the end of the film, Arnold Wright, an Army veteran himself, is shown in his home with his hands on his hips, standing over a box of his son’s military gear. He releases a sharp exhale before beginning to pull out his son’s uniform.

“The Army let me down,” he says in a voiceover. “They let my son down. And then they lied about it.”

‘He did it for love. He did it for the man standing next to him’

On Oct. 3, 2017, the day before the ambush, the 10-man team of ODA 3212 was tasked with a recon mission.

A U.S. drone had picked up the phone signal of Doundoun Cheffou, an ISIS subcommander, in Tiloa, a village near the border of Mali. The soldiers were assisted by two Nigeriens who had been previously trained by the Central Intelligence Agency to use a surveillance device that could lock onto Cheffou’s cell phone, ABC News reported on Nov. 13.

They traveled northwest from their base in Oulluam to Tiloa, roughly 30 miles away, but they found nothing, and began making their way back to their compound.

But as darkness began to fall and the team of U.S. and Nigerien forces neared their base the plan changed again: Cheffou’s phone signal was detected in “a different, more remote location on the Niger-Mali border,” according to ABC News. The team was instructed to head back toward the border where the signal was located. This meant moving at night to a new location where they would support another special operations team, ODA 3216, in a raid on a campsite of suspected ISIS fighters.

However, just hours later, the plan changed once more: ODA 3216 reported that they were unable to get to the campsite at the Niger-Mali border due to bad weather. They returned to their base elsewhere in Niger, which meant that ODA 3212 would be responsible for completing the mission, alone.

“Now, you might think the team would be thrilled to be the main reigning force,” James Gordon Meek, the ABC News investigative reporter who conducted the investigation into the ambush, says in the documentary. “After all, according to the AFRICOM report, they had just set out on a rogue mission to do exactly that.”

But that wasn’t the case. ABC News reports that after receiving word that his team would be the only one conducting the raid to capture Cheffou, the ODA 3212 commander, Capt. Mike Perozeni, strongly pushed back on the orders from his battalion commander, Lt. Col. David Painter. Perozeni’s objection focused on taking his team and their “exhausted” Nigerien partner forces into unfamiliar territory, where they’d have no backup or the possibility of a “speedy medical evacuation” if it was needed, according to the film.

It’s here that the narrative that the soldiers with ODA 3212 were a rogue team of operators begins to unravel.

It makes “no sense” to say that the team had gone out on an unauthorized mission on Oct. 3 to find Cheffou, considering that Perozeni was pushing back so strongly against the new orders, Maj. Alan Van Saun, company commander of ODA 3212, said in “3212: UN-REDACTED.”

“Why would he push back now if he was supposedly on board at the very front?” Van Saun said. “Why would he be expressing concerns about not being equipped or prepared if that was his intent all along?”

Despite the concerns raised by Perozeni, the commander of ODA 3212, Painter, who was hundreds of miles away from the team, directed the captain to move forward with the raid, according to ABC News. Col. Bradley Moses, the 3rd Special Forces Group commander based in Germany at the time, was also informed of the changes to ODA 3212’s mission, though he told ABC News that he wasn’t aware of Perozeni’s concerns.

“If someone told me that Mike Perozeni had concerns on his ability to execute the mission, I would have called him directly on a SAT phone … because nothing beats the ground truth if it’s coming from the ground commander,” Moses told ABC News last year.

Perozeni’s objections were not communicated to the families of the fallen soldiers, either. Arnold Wright says in the documentary that he was “left with the impression that this guy was a screw-up” who “carried my son off and got him killed.”

“That’s what I was led to believe,” Wright said. “And I think that’s probably the biggest injustice … I walked around pissed off for a year and my anger was directed towards somebody that was completely innocent of what they told me he did.”

Henry “Hank” Black, the father of Staff Sgt. Bryan Black, said in the documentary that he believes if Perozeni had been listened to, the soldiers “would be here today.”

But that wasn’t the case. Despite his concerns, Perozeni was overruled and told to take his soldiers and Nigerien partners forward to conduct the raid.

“They were told to go anyway,” said Debbie Gannon, the mother of Jeremiah Johnson. “They didn’t care that there was no backup for those boys.”

The team moved back towards the Niger-Mali border through the night of Oct. 3. When they reached the campsite on the morning of Oct. 4, they found that Cheffou had already left, and so they once again turned around and began heading back to their base in Ouallam.

It was a long journey back, and the convoy of U.S. and Nigerien forces pulled off near the village of Tongo Tongo to resupply and get water, ABC News reports. While there, they had an impromptu meeting with the village elder and other leaders in the area. The meeting lasted roughly half an hour longer than they’d expected, the documentary says, which the AFRICOM report said was likely intentional: the village elder is believed to have “deliberately delayed the convoy” to give enemy fighters time to set up the ambush that ODA 3212 would later drive into.

As the patrol left the village and made their way back to base, they started taking small arms fire. The convoy halted and reported enemy contact while returning fire, but the special operations soldiers and their Nigerien partners were seriously outnumbered. In the May 2018 press briefing, Cloutier said the team was outnumbered three to one by the enemy. ABC News reported it was actually 10 to one.

While Perozeni, LaDavid Johnson, and other soldiers were able to get out of the immediate line of fire, they quickly realized that Jeremiah Johnson, Black, and Wright hadn’t been able to follow them. Before they could turn back, they were pinned down by enemy fire. LaDavid Johnson “dropped to the ground under fire and ran south with two Nigerien soldiers,” both of whom were killed, according to ABC News. LaDavid made it another 900 meters to a tree where he attempted to take cover, firing back at the ISIS fighters, before he was killed.

Footage from a helmet camera worn by Jeremiah Johnson, which was taken by ISIS fighters after the battle and later retrieved by French Special Forces last year during an operation in which they killed the head of ISIS in the Greater Sahara, helps piece together the rest of the firefight.

The footage shows the three separated soldiers fighting through a chaotic situation after being separated from the rest of the team. When Black is shot and killed, Wright and Johnson expose themselves to the enemy to pull him behind their truck. While Wright and Johnson attempt to get to safety, they are pinned down by overwhelming enemy fire. At one point in the video, according to the ABC News, Wright is heard asking, “where is everybody?” Johnson can later be heard telling Wright that he’s been “shot seven times.”

In the documentary, Wright’s parents emotionally read aloud portions of the AFRICOM report, detailing what their son did: Returning to Johnson after he was shot, turning his own weapon on the enemy and firing until he was killed.

“I know what it took to take him down,” Dustin Wright’s older brother, Will, who also served in the Army and who has since re-enlisted, says in the documentary. “It makes me want to strap on my boots and go back. It does. I have no problem with how he went … He fought more than 10 men could fight, until his dying breath. He did it for love. He did it for the man standing next to him.”

‘A reckless mission that was concealed by senior commanders’

Some of the family members have watched the full 45-minute video of what happened that day. As painful as it is, for some it has brought a sense of closure.

At the premier of “3212: UN-REDACTED” in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 9, Debbie Gannon said that she watched her son’s head camera footage because she “had to find out some answers.” Johnson was shot 13 times, she said. She could only watch and listen to the first three.

“I’ve learned a lot more,” she said. “I wish I’d had this video prior to making this [documentary], because a lot more truth came out.”

And for these families, learning the truth is really what this documentary has been about. They needed to know what happened to loved ones — their son, their husband, their brother. They needed to know the real story, as opposed to the story they say they were told by the Pentagon.

Many of the details found in the documentary were not communicated to them, they said. They weren’t told about the CIA’s involvement in the first mission, an element of the story they believe was left out in order to push the narrative that the soldiers were acting on their own. They also weren’t told about Perozeni’s firm objections to the mission. According to ABC News, the family members said Cloutier “heaped blame on Perozeni for a reckless mission that was concealed by senior commanders.”

And those senior commanders have, for the most part, carried on unscathed by the events of Oct. 4. Both Lt. Col. David Painter and Col. Bradley Moses were promoted, according to the documentary, though their promotions were blocked by the U.S. Senate. Maj. Gen. Roger Cloutier, who carried out the investigation, was promoted to lieutenant general. Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, the head of U.S. Africa Command, retired in 2019 after classifying the redactions in the investigation report until 2043.

Meanwhile, Capt. Perozeni, who objected to the mission, received two potentially career-ending letters of reprimand called General Officer Memorandum of Reprimands (GOMORs), which were later rescinded. He was later awarded the Army Commendation Medal.

Maj. Alan Van Saun, the company commander who was with his wife who had just given birth to their daughter, also received a General Officer Memorandum of Reprimand, effectively ending his career.

Van Saun was reprimanded for failing to ensure that the soldiers of ODA 3212 “were adequately trained prior to conducting combined operations with the Nigerien partner force.” He said the general who delivered the reprimand “notified me that, more or less, my future in the Army was over.”

“My words to him were, ‘Sir, just so we’re straight here, just so I understand, so we’re on the same page: You’re essentially ending my career over something that I was not part of, nor did I have authority over. ODA 3212 was trained and certified and validated by Lt. Col. Painter and Col. Moses,’” The general quickly changed the topic, Van Saun says in the film.

Retired Gen. Donald Bolduc, the former commander of Special Operations Command-Africa, said in the film that Painter and Moses weren’t held accountable because they are “card-carrying members of the club.”

“[Van Saun] was a scapegoat to protect higher officers from being punished,” Bolduc said.

Myeshia Johnson also questions Van Saun’s punishment: “They gave him a reprimand,” she says in the film. “For what? He wasn’t even … there. His daughter was born the same day my husband died, and I’m pretty sure that eats him up every day.”

Highlighting the lack of accountability, and pushing for more, is a big reason why Gannon, Jeremiah Johnson’s mother, chose to be involved in the film in the first place. She said at the documentary premiere that she wants people to know the real story about what happened in Niger on Oct. 4, 2017.

“I want Moses and Painter held accountable. They go to bed every night, they don’t think at all about my boy. They wake up every morning and they wake up and go about their day. There’s not a day that I don’t wake up and think about him, or go to bed at night and think about him,” she said, crying. “Is it revenge? Yes there’s a part of it that’s revenge. But also so they can’t do this to another family … it’s never going to end for us. And if it stops their career, and they can’t do it to somebody else, and they wake up in the morning with no career, at least they’ll think about what they’ve done.”

More great stories on Task & Purpose

- A Marine actually got a tattoo based on that cringe viral ‘He’s a Marine’ TikTok video

- Meet the Army sergeant who ran a makeshift orphanage in Kabul to care for children during the evacuation

- Hollywood is already making a movie about the Afghanistan withdrawal

- No ‘surrender’ — What really happened between US and British Marines at a training exercise

- Marine Corps throws cold water on fighter jet rides for reenlistment

- A woman just graduated the US Army’s sniper school for the first time ever

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Learn more here and be sure to check out more great stories on our homepage.