The Air Force is looking into a possible association between cancer and missile combat crew member service at Malmstrom Air Force Base, Montana after a Space Force lieutenant colonel discovered that some former Malmstrom missileers developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) after serving at the base between the late 1990s and the late 2000s.

About 1 in 80 missileers who served at Malmstrom between 2004 and 2007 developed NHL, said Space Force Lt. Col. Daniel Sebeck, himself a former missileer diagnosed with NHL, in a briefing he made on the issue for Air Force and Space Force leaders that was shared on the popular Air Force amn/nco/snco Facebook page on Saturday.

The 1-in-80 rate is much higher than the general population incidence rate of 1 for every 9,091 people, according to a figure Sebeck said came from the New York Health Department. Although Task & Purpose could not verify the New York Health Department estimate, the National Institutes of Health found that the rate of new cases of NHL was 19 per 100,000 men and women per year.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

According to Sebeck, at least 10 service members associated with Malmstrom developed NHL after working there between 1997 and 2007. Two other service members developed Hodgkin’s lymphoma and 24 others developed some form of cancer. Eight of these service members have since passed away, Sebeck noted. Many of the aforementioned service members served in missile units at Malmstrom.

“I’ve lost two friends over the last two years and two more are undergoing the same diagnosis, which is itself alarming,” said one former missileer who served at Malmstrom and who spoke with Task & Purpose on the condition of anonymity. All four friends had been diagnosed with NHL in their 30s or 40s, even though the condition is most common in people 60 or over, according to the Mayo Clinic.

“I feel two emotions: one is ‘holy cow, what is going on with my friends,’ and two: ‘is this something I should be worried about?’” said the former missileer. “When I go for my annual physical I’m going to ask for a much more robust battery of tests.”

In a statement, Air Force spokesperson Ann Stefanek said that service senior leaders are aware of Sebeck’s report.

“We are heartbroken for all who have lost loved ones or are currently facing cancer of any kind and know that we have the responsibility to investigate any potential service-related risks to airmen, guardians, or their dependents’ health,” she said. “The information in the briefing has been shared with the Department of the Air Force Surgeon General and our medical professionals are working to gather data and understand more.”

Chemical cocktail

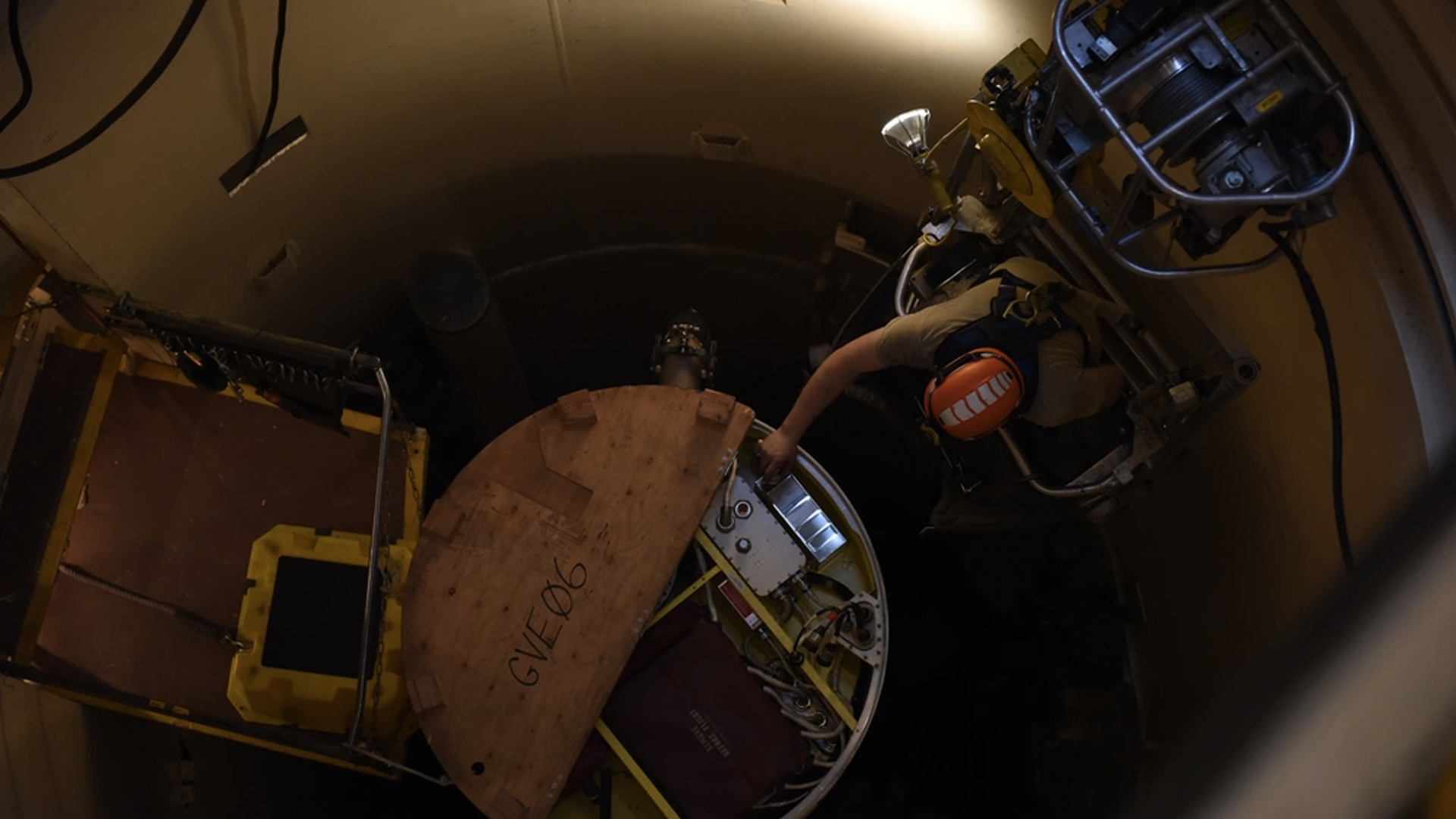

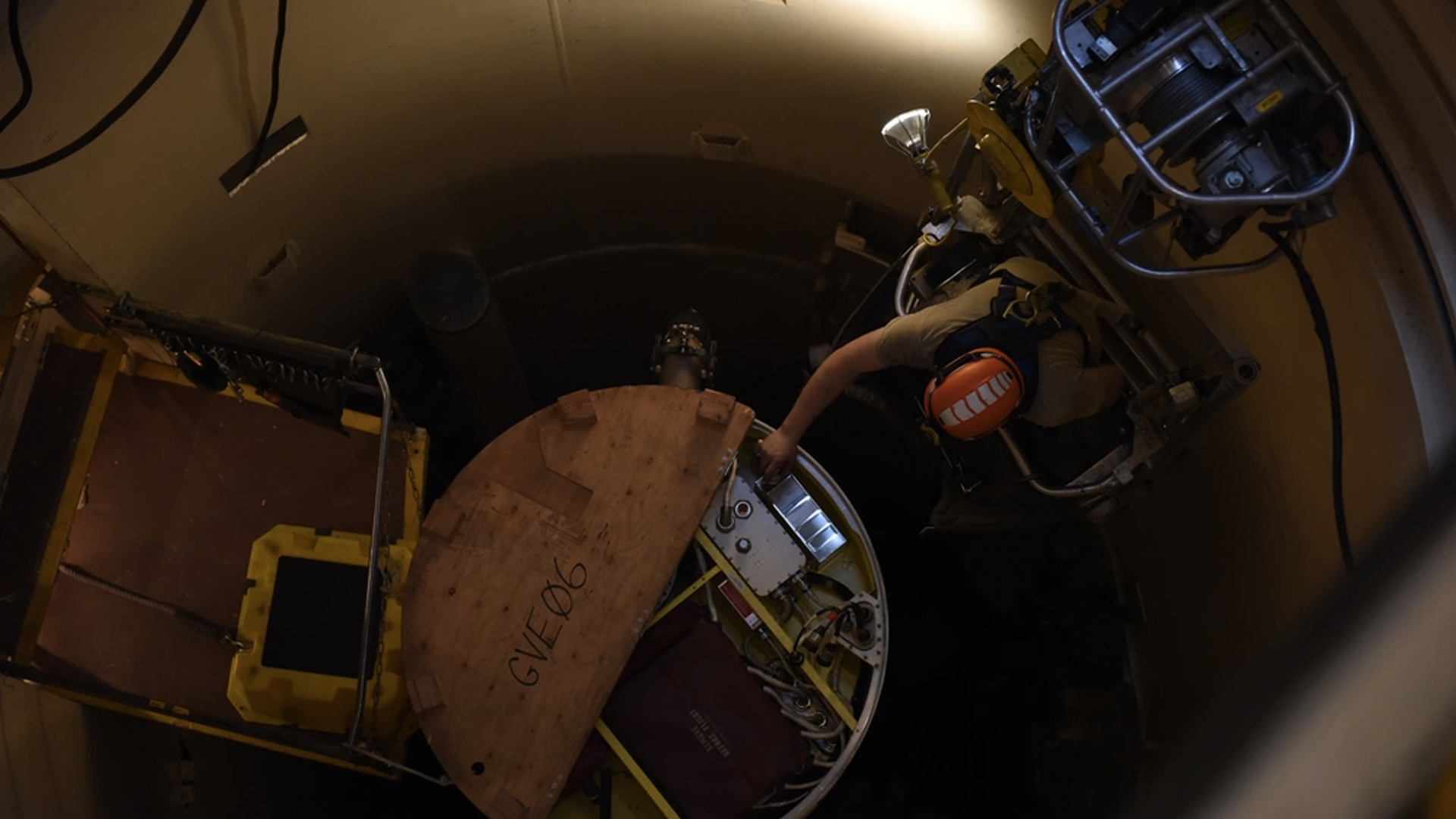

Air Force missile crews are exposed to a witches’ brew of carcinogens while working in the launch control centers (LCCs) buried 60 to 90 feet underground, according to Sebeck’s report. Working in pairs, missileers “pull alert” in those LCCs, meaning they spend long shifts ready to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles such as the Minuteman III. Malmstrom alone has 15 missile alert facilities and 150 launch facilities spread over a 13,800 square-mile complex, according to the base website. Similar facilities exist at Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota, and F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyoming.

The problem with these facilities, Sebeck said, is that much of the equipment and infrastructure dates back to the 1960s and 1970s and operates using carcinogenic chemicals. When 1960s-era components of the Minuteman III system overheat, they off-gas electrical component insulation and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), Sebeck wrote. PCBs were banned in the U.S. in the 1970s, according to the National Institutes of Health, and long-term exposure to high levels of the chemicals may cause cancer.

In the launch control centers at Malmstrom, missileers can also be exposed to PCBs when water intrudes into the Minuteman III electrical power distribution systems and then leaks into the LCC, Sebeck wrote. There is also asbestos from floor tiles and piping insulation in the LCCs, which missileers are exposed to when they remove and replace the floor tiles to check the under-floor inventory of survival equipment at least once a month, Sebeck said.

Another chemical, ethylene glycol — which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said is not classifiable as a human carcinogen but which can affect the central nervous system, heart and kidneys — “continually leaked and evaporated” in the LCCs when it was used in air cooling units, Sebeck wrote.

Sebeck said that missileers are also exposed to Radon, a radioactive gas released from the decay of elements such as uranium and radium, which can substantially increase the risk of lung cancer “in areas without adequate ventilation, such as underground mines,” according to the National Institutes of Health.

Sebeck also noted that missileers often burned nuclear, biological, and chemical-resistant cryptographic paper and classified materials in the confined space of the LCC. Missileers at other installations like Minot and F.E. Warren had classified material shredders at each LCC, he said, but the configuration of the LCCs for the Malmstrom-based 341st Missile Wing did not allow for such a shredder, so the missileers there had to burn classified materials more often.

The former missileer who spoke with Task & Purpose noted that most missile crews are aware that the combination of old facilities and old safety standards “creates a lot of potential exposures,” but there has never been a rigorous effort to study those exposures of their long-term effect on airmen. Sebeck called for such a study in his briefing.

Lack of awareness

The fact that LCCs have dangerous chemicals is not new to missileers, who have to sign an Air Force Form 55 Employee Safety and Health Record acknowledging there are hazardous materials in the work environment, Sebeck noted. According to Sebeck’s briefing slides, the Air Force does not have a proactive system for monitoring the health of airmen who work in those environments.

“The known hazards combined with the lack of tracking, education, monitoring, screening and awareness of missileer health issues at the service level is concerning,” Sebeck wrote. “This concern is amplified by the disproportionate number of missileers presenting with cancer, specifically lymphoma.”

Sebeck noted that the Air Force completed a limited study of cancer at Malmstrom in 2001, but he said the study “was condensed, did not consult third parties, utilized incomplete data, and was not available to the impacted family members and crew members.” The Air Force also released an executive summary of the study in 2005 that concluded the LCCs are safe and healthy working environments, but Sebeck said that finding does not hold up considering how many of his fellow missileers have been diagnosed with forms of cancer.

“[Twenty-one] years later, the study’s conclusion is challenged by the current NHL incidence rate and deserves further attention,” the guardian wrote.

Sebeck made four recommendations to improve the situation. The first is that the Pentagon should “take a proactive stance” toward screening and tracking missileers for lymphoma and other cancers through education and medical tests. The second is that the Air Force and an independent third party should conduct a formal study of cancer among missileers, maintenance personnel and their families.

The guardian’s third recommendation is for the military to better educate missileers on safety precautions for limiting their exposure to toxic chemicals and involve third parties in health and safety tests of the missile facilities. The last recommendation is for the Air Force to make missileers’ record of toxic exposure a part of their permanent medical record and to screen and track those airmen for the rest of their lives in order to catch related conditions early and provide the right care.

Sebeck wrote that he has informed dozens of current and former missileers about the high cancer risks, but he “does not have the resources and reach” that the greater Air Force could use to reach all the missileers who need to hear about it.

The former missileer who spoke with Task & Purpose said the reception to the leaked briefing within the missile community has been positive based on what he has seen on social media so far.

“I would estimate that everybody’s feeling like I feel,” he said. “Missileers are very proud of what we’ve done to serve our nation, and we understand it is critical, so let’s get it right and be able to do this mission safely going forward.”

More than just missiles

Should Sebeck’s briefing prove accurate, it would not be the first time a specific Air Force career field has been found to have a higher risk for cancer.

In 2021, Air Force scientists released a study finding that male fighter aviators between 1970 and 2004 were 29% more likely to be diagnosed with testicular cancer than their fellow officers, 24% more likely to be diagnosed with melanoma, and 23% more likely for prostate cancer. Compared to the general population of U.S. males, fighter aviators were 25% more likely to be diagnosed with melanoma skin cancer, 19% more likely for prostate cancer and 13% more likely for NHL.

Other factors of military life besides career fields can also present cancer risks. For example, many veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were exposed to airborne hazards through the smoke and fumes emanating from open-air burn pits.

Closer to home, the Pentagon found 24 locations where the military was the drinking water purveyor and the concentration of carcinogenic PFAS chemicals were higher than Environmental Protection Agency limits. The number of people able to be served by those locations at the time was 175,000, the Pentagon wrote in a report last year, but there are likely 640,000 people served at other locations with PFAS levels greater than deemed safe by the EPA, according to one advocacy group.

“The Defense Department may be underestimating by hundreds of thousands the number of people at military installations drinking water contaminated with the “forever chemicals” known as PFAS,” wrote the Environmental Working Group in its response to the Defense Department report.

It seems even non-combat military service can be hazardous to your health. If Sebeck’s findings are accurate, the Air Force may have an opportunity to at least better track and treat the possible consequences of missile crew duty. The former missileer who spoke with Task & Purpose was hopeful for that opportunity.

“In terms of changes, the most important thing we would love is a modern, well-informed study done with rigorous methodology and transparency,” he said. “Make it the best study you can do in 2023.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

- The Navy wiped the ‘Top Gun: Maverick’ director’s camera after he ‘captured something I wasn’t supposed to capture’

- Marine under investigation after viral video showed altercation with hotel staff

- Fighter pilot to receive Navy Cross more than 70 years after classified dogfight with 7 Soviet jets

- 2 Navy commanders fired in one day

- The Marines have a new ship-killing weapons system to counter China

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here.