The U.S. Navy’s plan to decommission 24 ships next fiscal year has garnered universal scorn from naval experts as well as members of Congress, who feel the Navy cannot afford to shrink while China’s Navy continues to grow.

“China has clearly shown their ambitions in the Pacific: Their aggressiveness toward Taiwan,” Rep. Elaine Luria (D-Va.) told Task & Purpose. “The Navy is the reason that we have the world order that we have today post-World War II. We cannot cede that maritime supremacy in the Pacific to the Chinese. It requires our presence and that requires ships, and that requires investment.”

The Navy’s latest budget request calls for reducing the size of the fleet from 298 to 280 vessels by fiscal 2027. Meanwhile, China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy already has at least 355 ships, making it the largest navy in the world.

The day after the Navy announced its budget request for fiscal year 2023, Luria tweeted exactly how she felt about it: “It sucks.”

“China is not a ‘pacing challenge’ when they will soon have double the size of our Navy,” tweeted Luria, a retired Navy commander and former nuclear-trained surface warfare officer. “We are losing 1000+ [Mark 41 Vertical Launching System] cells, with NO PLAN to replace them. Instead, we are investing in the next ‘Gucci’ missile and technology that will not be mature for 20+ years.”

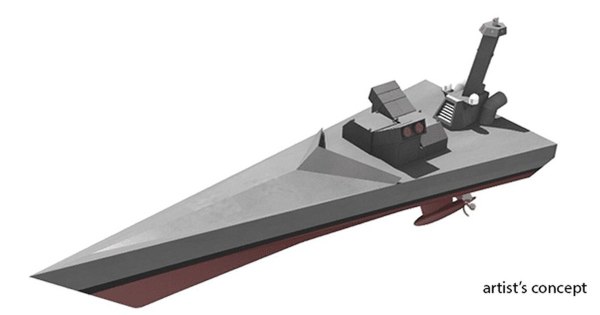

The vertical launching system cells are used to fire Tomahawk Land Attack missiles — the Navy’s long-range ship-launched weapon — as well as air defense, ballistic missile defense, and anti-ship missiles, Luria said. While the Navy is considering unmanned ships to launch missiles, those vessels would not be available until “far in the future,” she said.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

It will be quite a while before the Navy can start replacing the ships it plans to decommission with new vessels. The design for the Constellation-class frigate has not yet been finalized and the first ship won’t be delivered until 2026 at the earliest. The $13 billion aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford provides a cautionary tale of how long it can take to get the bugs out of new technology. Commissioned in July 2017, the Ford was originally supposed to deploy the following year, but after a series of delays it is now expected to make its first deployment this fall.

The problems with the Ford are not an isolated incident. For the past two decades, the Navy’s shipbuilding efforts have been plagued by a series of disasters. The Zumwalt destroyer program only produced three of the 32 ships that the Navy had hoped for. Moreover, the Zumwalts were originally designed with a gun to support troops ashore, but in 2016 the Navy canceled the program making the gun’s rocket-propelled shells, each of which cost $800,000. The Navy’s latest plan is to begin fielding hypersonic missiles on Zumwalt destroyers starting in fiscal 2025.

The Navy’s biggest setback has been the Littoral Combat Ship, which was originally supposed to be able to do three missions: surface warfare, mine countermeasures, and anti-submarine warfare. Now, it can barely do its surface warfare mission, and the Freedom-variant’s propulsion system remains hamstrung by a vexing design flaw that limits the ships’ speed.

In fact, nine of the ships that the Navy wants to decommission are Freedom-variant Littoral Combat Ships: USS Fort Worth, USS Milwaukee, USS Detroit, USS Little Rock, USS Sioux City, USS Wichita, USS Billings, USS Indianapolis, and USS St. Louis. All these ships have been commissioned since 2012 and some are just three or four years old.

Luria said she believes the Freedom-variant is a failure, but she faults the Navy for not building as many new ships as possible to replenish the fleet’s numbers. The Navy has been focused on working within its share of the defense budget rather than coming up with a strategy and determining how many ships it needs.

“I just feel that in our current circumstances and world environment, we need to build all that we can build with the capacity that we have,” said Luria, who added she has been pushing Navy officials to clearly state what the risks are of not building a bigger fleet. “Every year since I’ve been in Congress, we’ve received a budget that wants to reduce the size of the Navy.”

Some of Luria’s colleagues across the aisle have also expressed their disdain for the Navy’s request to decommission 24 ships.

“I am highly skeptical of any plan that decommissions so many battle-ready warships without a serious plan to replace their capability,” Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) told Task & Purpose.

“Our world is getting more dangerous, not less. Russia continues to test the mettle of Europe and our NATO allies. China is building its third aircraft carrier and recently surpassed the United States with the largest naval fleet in the world. Our top admirals tell us Taiwan could be under threat within the decade, and we are unprepared.”

Wicker described the Defense Department’s overall budget request as “inadequate,” and he indicated that lawmakers could reverse the planned cuts to the Navy’s size.

“Congress will have to step in to correct this course and provide the resources necessary to rebuild American seapower,” Wicker said.

Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) claimed that President Joe Biden is not providing the Navy and Air Force with enough funding in the Defense Department’s fiscal 2023 budget request.

“We should be bolstering our military right now to protect America and show our leadership in the world, and his proposal falls well short,” Ernst told Task & Purpose.

However, Navy leaders argue that when it comes to seapower, fleet size isn’t everything. Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro has acknowledged that China has 17 shipyards, and it is expected to have 450 ships by the end of the decade, but on March 30 he argued that U.S. Navy ships “significantly outpace the qualities and the capabilities” of Chinese vessels.

“You said that China is really good at building ships. I would argue differently: They’re probably not that great at building ships but they build them in great numbers,” Del Toro told Steve Clemons, editor at large for The Hill, during a Future of Defense Summit.

Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Michael Gilday has said that while the Navy ultimately needs to have more than 500 ships, the fleet cannot be too big to sustain. “We need a ready, capable, lethal force more than we need a bigger force that’s less ready, less lethal, and less capable,” Gilday said on Monday during the Navy League’s Sea-Air-Space Exposition.

“Given our topline and given the fact that we can only have so many ready ships that are manned properly, that are trained properly, that have ammunition in their magazines, that have the proper amount of maintenance, in order to do that, we’ve had to make some very difficult decisions about divesting of some platforms,” Gilday said. “It’s more than just a numbers game. It is a capabilities and a numbers game about fielding a combat-credible force that can deter.”

“If you want to talk just about capability and you want a force that is ineffective, take a look at the 125 BTG [Battalion Tactical Groups] that Vladimir Putin has positioned around Ukraine,” Gilday continued. “That’s not the force that any of us want.”

However, naval experts take issue with Navy leaders’ argument that quality always trumps quantity. Chinese Navy ships have fewer missiles per vessel, but that means the People’s Liberation Army Navy can afford to lose more ships than the U.S. Navy, said retired Navy Capt. Brent Sadler, a former submariner who is now the senior fellow for naval warfare and advanced technology at the conservative Heritage Foundation think tank in Washington, D.C.

“They can take a hit,” Sadler said. “They’ve got their eggs distributed thinly and they’ve got more ships than the U.S. Navy already. So, if you go sink one Chinese destroyer, they haven’t lost a lot of capacity — their firepower is not destroyed when you take out one. If you take out one of our destroyers, you’ve taken out a significant proportion of our firepower. That’s the dynamic that’s at play here.”

Another issue is that the Navy is already overworked, so as the fleet gets smaller it will mean that ships will have to deploy longer and more frequently over the next decade, said retired Navy Cmdr. Bryan Clark, a senior fellow with the Hudson Institute think tank in Washington, D.C.

“They will then need more maintenance and repair, reducing availability and further stressing the smaller number of available ships,” Clark told Task & Purpose. “This vicious cycle of shrinking fleet, reduced readiness, and further stress is what I worry about. Very quickly the U.S. Navy could find itself unable to sustain enough Western Pacific presence to exploit its qualitative advantages before the PLA [People’s Liberation Army] grows to the point where it can challenge the U.S. Navy for open ocean dominance.”

Clark also suggested that the Navy could avoid retiring all nine of the Freedom-variant Littoral Combat Ships by forward basing four of the ships in Bahrain while having the others undergo maintenance in the United States, where they could be used for homeland security needs. “That approach could allow the Navy to get by with fewer Freedom class [ships] and retire only four or five instead of nine,” he said.

Meanwhile, China is not only building new ships much more quickly than the United States, it is also developing modern cruise missiles and anti-ship ballistic missiles that pose a threat to the U.S. Navy, said Blake Herzinger, a non-resident WSD-Handa Fellow at the Pacific Forum foreign policy research institute.

To some extent, decommissioning older and inadequate ships makes sense because it stops throwing good money after bad and the savings can be used to build new vessels, Herzinger told Task & Purpose.

“But the navy needs ships to do its job, and it’s very unlikely that this reduction in hulls will be accompanied by a commensurate reduction in tasking or responsibilities,” Herzinger said. “Any ships being either built or developed with that money we save are years away, and we are in dire need of more hulls now. As Ned Stark and some of our more public-facing navalists have said for some time now, ‘Winter is coming.’”

What’s new on Task & Purpose

- Air Force investigates cargo plane crew for ‘unplanned’ landing to pick up motorcycle in Martha’s Vineyard

- ‘Top Gun’ sequel isn’t even out yet and we already know they f–ked up the uniforms

- The Marine Corps has an eating disorder problem

- The Army knows its op-tempo is ‘unsustainable’ but can’t seem to fix it

- ‘Call that a good day’ — An American is live-tweeting his part in the war in Ukraine

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.